What Does Upgrading To A Better Camera Actually Get You?

Does the camera matter? It sure does, in a few crucial ways.

We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

It’s the photographer who makes the picture, not the camera, right? Right—up to a point. As cameras go up in price, they often go up in sophistication; costlier models boast features that can tackle shooting situations entry-level models simply can’t. And, of course, a better camera can make taking great pictures easier and more enjoyable.Is it time to step up to a higher-level DSLR or mirrorless interchangeable-lens compact? Here are 10+ ways an upgrade could give your photography a boost.

Gain More Control

More expensive cameras tend to have more dedicated buttons, dials, and switches, plus more options to customize settings to suit your shooting style. Some mid-level and higher-end DSLRs and ILCs sport joysticks for faster autofocus-point selection. Not to mention the dual command wheels, present in models in the mid-range and up, which make manual shooting smoother.

Higher-end bodies have the latest output ports, such as USB 3.0, or even Ethernet in the most expensive DSLRs.Certain camera features get ampedup when you step up, too.

Higher-end cameras allow a wider range of exposure compensation and let you shoot at plus or minus 5 EV rather than the 3 EV found in entry-level bodies. Pricier models may allow more shots per bracket when auto-bracketing. And you can make multiple exposures of up to 10 frames with some pro-level cameras, while lower-end cameras might limit you to two, if any.

Nikon

Nothing ruins a day like a dead camera battery, and you may not always have a spare on you. With DSLRs, battery life increases significantly in the better bodies. Canon’s EOS Rebel SL1, for example, which uses a smaller battery than Canon’s other DSLRs, checks in with 380 shots, similar to the Pentax K-S2’s 410 shots. Move up to Pentax’s K-3 II and you’ll jump up to 720 shots. Canon’s EOS 5D Mark III is capable of 950 frames before the battery dies, while the Nikon D750 boasts 1,230. Stepping up to the Canon’s 1D X Mark II will bring you up to 1,210, while Nikon’s D5 can nab an incredible 3,780 frames before the battery depletes.

ILCs and their power-hungry EVFs, on the other hand, typically don’t fare very well when it comes to battery life, no matter how high-end they are. Fujifilm’s hybrid finder demonstrates exactly how much of a drain an EVF can be. When using its optical finder with projected frame lines, the X-Pro2 gets 350 shots per charge, but that drops to 250 when using the EVF. Sony’s Alpha 7R II’s weakest aspect is probably its mere 290 shots per charge.

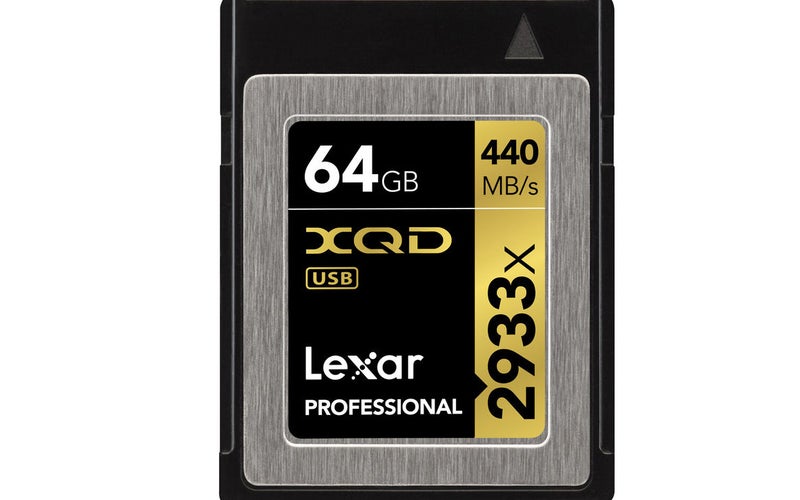

Lexar

When you think of a memory card, you probably think of an SD or a CompactFlash (CF) card. But if you want to get the most shots per burst, or record 4K or very high frame-rate video, you should use a card that is more advanced than a standard SD or CF.

Nikon and Canon’s top DSLRs are essentially phasing out the CF card and this means a format war. Nikon was the first to go for a new kind of card, introducing an XQD slot along with a CF slot in its D4s. Canon has now followed suit with a CFast 2.0 slot next to its CF slot. Nikon’s latest, the D5, can be had with either two CF slots or two XQDs.

Meanwhile, UHS-I and UHS-II SD cards have allowed faster writing speeds than ever.

On a more practical level for still shooters, mid- and high-level bodies tend to have two card slots, while entry-level bodies limit you to one. With a second slot, you can have the camera automatically switch to the second card when your first is full. Or you can tell the camera to record RAW to one card and JPG to the other. A second slot can provide peace of mind and also help you organize.

Sony

While some entry-level models let you shoot JPEGs until your card is full, that’s usually because their burst rates are slower and pixel counts lower than more advanced models. But if you want to shoot RAW instead of JPEG, pricier cameras give you deeper buffers—one of the more reliable benefits of stepping up. For instance, Canon’s EOS T6s can shoot at 5 frames per second until your memory card is full, but switch to RAW and you’ll max out at 8 frames before you have to pause your shooting. Stepping up to the EOS 80D will get you 25 RAW shots at 7 fps before its buffer fills, and the full-frame 5D stores 18 RAW shots at 6 fps.

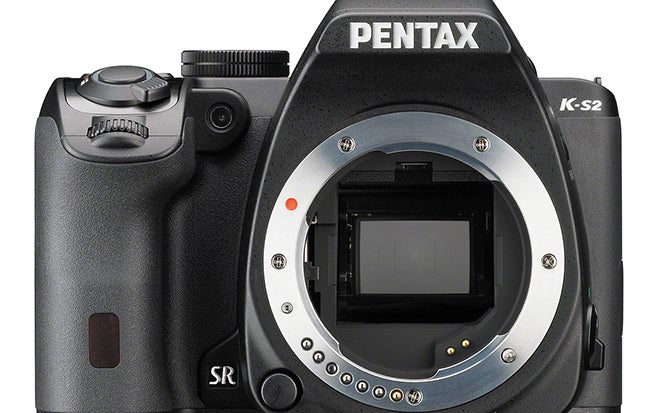

Pentax

The underlying chassis of some entry-level cameras are made from plastic parts and are less likely to have weather sealing. Mid-range and higher-end models are usually built with a tough yet lightweight magnesium-alloy chassis—a sign that the body is built to last. Couple that with solid weather sealing and you’ll be ready for tougher conditions.

Ricoh’s Pentax line, for example, includes serious weather sealing across all of its DSLRs, but the K-S2, its step-up model (one notch above its entry-level DSLR), has more than 100 weather seals.

Canon

Less expensive DSLRs and ILCs tend to have APS-Csized sensors that have about 40 percent of the surface area of a full-frame 35mm sensor. With less room, APS-C format cameras have to use smaller pixels compared with full-framers to achieve the same pixel count. If all else is equal, these smaller pixels generally bring with them more noise. So a switch to a camera with about the same pixel count but a larger sensor should yield cleaner images at higher ISOs. Micro Four Thirds (used in Olympus and Panasonic ILCs) and 1-inch sensor sizes are smaller than APS-C, and the same rules apply.

While better noise performance is generally desirable, sometimes you just want all the pixels you can get. Canon’s 50.6MP EOS 5DS currently boasts the most pixels of any 35mm-format (full-frame) camera, and Sony’s 42.4MP A7R II follows pretty close behind. Both offer images with tons of fine detail, but can’t match the clean images at higher ISOs that you’ll get from even more expensive cameras, such as Canon’s EOS-1D X Mark II and Nikon’s D5. So within a given camera system, stepping up to a more costly body can gain you cleaner images, but how much cleaner will depend on whether you prioritize clean images or super resolution.

Fujifilm

Whether you prefer optical or electronic viewfinders, you’ll get superior accuracy and greater maximum magnification when you upgrade. Most entry-level DSLRs give you only 95-percent accurate finders—that is, you see only about 95 percent of what will end up in the image while you shoot—making precise framing more difficult. (Electronic viewfinders tend to provide 100-percent accuracy at all levels.)

Magnification refers to how large the frame will look compared to how you view the world with your naked eye. The lower the magnification, the more of a tunnel-vision effect the finder will have. Most APS-C-format, entry-level DSLRs do OK, with magnification specs around 0.8X or slightly higher, while less expensive full-frame models can get as low as 0.7X. If you step up to a finder with 1.0X magnification, you’ll be able to shoot comfortably with both eyes open, which is useful if you need to see what is outside the frame as you work. While EVFs are typically 100% accurate, they vary in magnification, so stepping up still has benefits. If you prefer a true rangefinder instead of a prism or an EVF, your only current option is a Leica. But Fujifilm’s top-of-the-line X-Pro2 offers a unique hybrid finder that is the closest approximation of a rangefinder we’ve seen, while also letting you switch to an EVF.

Olympus

In the world of DSLRs, laying down more dollars will let you capture more shots with a single press of the shutter button. Entry-level cameras typically offer a continuous drive at about 5 frames per second; mid-level bodies amp bursts up to 7 fps. And the highest level DSLRs can go as fast as 14 fps with full metering and focusing between frames, or 16 fps if you lock the mirror up, which means that you limit yourself to the AF available in live-view or video mode.

These rules don’t apply to mirrorless cameras. ILCs often cite fast burst rates, but they usually lock both focus and metering before the burst begins. So if you pan across an area with changing lighting conditions or if the distance to your subject changes, you may have to revert to a slower burst rate unless you go up the line.

AUTOFOCUS PRECISELY

When it comes to DSLRs, their phase-detection autofocus systems can have as few as 9 focusing points or well over 100. But the number of focusing points doesn’t tell the whole story.

That 9-point system might only have one cross-type focusing point (think a plus sign instead of a minus sign) in the center that can handle only lenses with an f/5.6 maximum aperture or larger. At the other end of the spectrum, Nikon’s high-end D5, for example, has 153 AF points, all sensitive to f/5.6 or larger, 99 of which are cross-type and 15 of which allow maximum apertures as small as f/8. If you use long telephoto lenses with teleconverters, you may end up with a lens that is the equivalent of an f/8 maximum aperture. Sometimes a better camera body can mean the difference between being able to use AF or not.

The distribution of those AF points also matters, especially when you’re trying to track a subject. Nikon’s D500 uses a full-frame AF system in an APS-C format body. As a result, the AF points reach further towards the sides, top, and bottom of the frame, thereby extending the areas of effective AF tracking. It also keeps you from having to lock focus and recompose, which is best avoided if you’re shooting wide open with fast glass.

When it comes to ILCs, there’s less variation in capabilities, but you’ll typically find the fanciest systems in the pricier models. The hybrid contrast/embedded phase-detection systems do sometimes include more phase-detect points, or more selectable areas, in pricier bodies. They also push the sampling rate faster to speed up the focusing process.

Sony

This is an area where the best is really at the top of the line, but some less-expensive cameras still deliver more than you might expect. Nikon’s D3300, an entry-level DSLR, can record 1080p video at up to 60 fps. This can help create smoother looking, normalspeed video, or let you do half-speed slow motion. Meanwhile, for the price of a mid-level DSLR, you can use Panasonic’s Lumix GH4 to shoot 4K at 24 fps, or 1080p at 60 fps. At the highest level, Nikon’s D5 will let you record 4K at 30 fps or 1080p at 60 fps, while Canon’s 1D X II allows 4K capture at 60 fps or 1080p at up to 120 fps.