Shooting With The 20×24 Polaroid Camera: The End Of An Era

A legendary photographic format will soon cease to exist

Pop Photo Visits the 20×24 Studio by popphoto

For me, it all started with a dog on roller skates. William Wegman’s 1987 photo “Roller Rover” was the first photograph that I can remember learning was shot using a Polaroid 20×24. At that point, the cameras (Polaroid made five in the late 1970s) had been in use by artists for close to a decade.

But I didn’t know about them until I found myself captivated by the original print’s lifelike detail and rich tonality—even more than by its humorous conceit.

Once I knew to look, I saw the 20×24 everywhere: Chuck Close’s photographic self-portraits, David Levinthal’s tiny cowboys and bathing beauties. Later on, Mary Ellen Mark’s black-and-white portraits for The New Yorker.

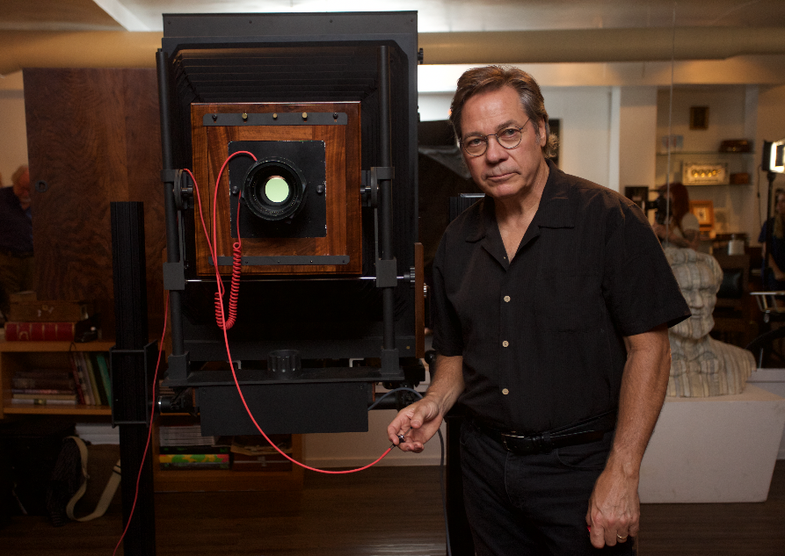

I finally saw the camera itself during a weekend workshop in 1997 taught by John Reuter, an artist who ran Polaroid’s 20×24 program for nearly all of its existence—and who continues to run the 20×24 Studio today. I immediately fell in love with the massive view camera, with its bright red bellows and rolling stand. But I never had the chance to see it in action, until a deadline loomed.

A few months ago, Reuter announced that the 20×24 Studio would cease operations in 2017. His company has been slowly using up the instant film stock it bought from bankrupt Polaroid in 2009 and mixing and packaging the chemical reagent necessary to produce these instant prints.

When I learned the news, I thought, “Why mourn now? Let’s rent the camera and write about the experience!” So we booked the New York studio and decided to make a group portrait of our staff. We met John Reuter and his colleague Nafis Azad in Tribeca on a hot day in July. They operate the camera and manage all of the technical aspects of the shoot. For us, Reuter set the focal length and overall framing, while Azad, under a black drape, focused precisely. Then Reuter tripped the shutter and popped the strobes.

The exposure process requires two rolls of film—a 150-foot roll of negative and a 50-foot roll of positive—plus a foil pod filled with reagent that acts as the developer. The negative reacts to the exposure in the camera; rollers inside the camera’s processor back spread the reagent at the point where the negative and positive meet to transfer the image as you pull the sandwiched film from the camera. You cut it away from the camera, wait 90 seconds, peel off the negative, and—voilà!—there’s your unique print.

Want to book a session? Reuter and his team can take a camera anywhere in the U.S. It will cost you, though perhaps less than you think—we spent $3,375, including the cost of 13 exposures (there’s a minimum of 10). Learn more at 20x24studio.com. It’s your last chance for the ultimate in analog photography.