Tips From a Pro: Damian Strohmeyer On Shooting Better Sports Photos

Bring your photo A-game to the big game

Freeze Action

Get Down

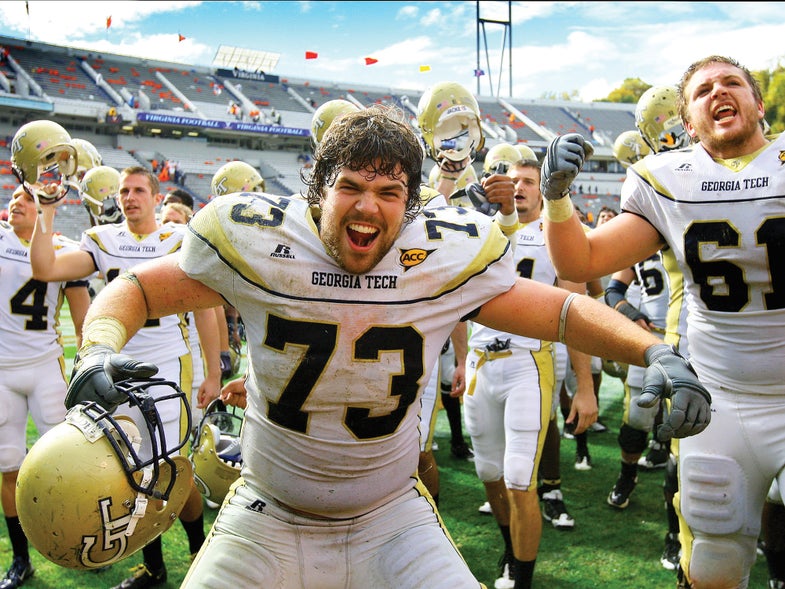

Stay Past the End

Choose Your Focus

Go Up

Capture the Fans

Over a career spanning nearly three decades, Damian Strohmeyer has scored 70 Sports Illustrated covers. Five of his images appear in SI’s 100 Greatest Sports Photos of All Time. He’s shot World Series, Super Bowls (27 of them), NCAA basketball, and the Olympics. His other clients run equally top-shelf: Canon, Nike, Major League Baseball, the US Golf Association, Boston University, Carnegie Mellon University, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post. Strohmeyer says his success comes down to a few simple rules. Among them: Be prepared, be courteous, and be knowledgeable. And of course, take excellent pictures. Here he shares his secrets for making gold medal worthy sports photos.

Be Prepared

“I don’t mind being out-photographed,” Strohmeyer says. “I really mind being out-thought.” Shooting sports is no more unpredictable than any other assignment. Which is to say, it is always unpredictable. While some photographers enjoy the thrill of working without a net, Strohmeyer has always preferred a more Boy Scout–like approach. “You want to be flexible, and you want to be able to handle unusual requests or last-minute requests, but to do that it helps a lot to be prepared,” he says.

“The day before the job is when I put all the thought processes in order,” Strohmeyer says. “What equipment am I going to need? What’s the client looking for? Checking the weather if it’s an outdoor event, checking the lighting if it’s indoors.” He plans his shots based on the venue’s sightlines, any remotes he plans to set up, and, depending on the game, according to individual players’ tendencies. “The more little things you can get out of the way before the shoot, the more time you’re going to have to concentrate on the actual photographs,” he says.

When traveling, Strohmeyer advises, always carry backup: batteries, flashes, and lenses. “Obviously you don’t travel with two 400mm f/2.8s,” he says. “It’s not really practical. But if it’s a big enough job, I’m going to have two 70–200mms in case something breaks down.”

And backup isn’t limited to gear. It’s also the network of people you can call on to bail you out if FedEx delivers a case to the wrong place, you leave your monopod at home, or worse, something breaks. “If my 400mm f/2.8 were damaged before a football game, there’s somebody I can call who can get me through that job,” he says.

Tell A Story

Whether it’s a shoot for editorial clients or commercial ones, your pictures will need to communicate. A lot of that communication depends on your ability to express yourself creatively, Strohmeyer says. But even the most interesting subject will lose impact against a background that’s lousy.

So what makes a background work? “You want the background not to subtract from the picture,” Strohmeyer says. If it enhances the image, that’s even better. Shooting golf? Use the course’s sand traps, green grass, and trees. The golden glow of a basketball court can work when the players’ uniforms have a lot of contrast; a brightly shaded key area (under the basket) can be even better. If you can find them, wide swaths of pure color will often add to the photograph.

Alas, those kinds of backgrounds aren’t made to order, and you’ll need to do what you can to compensate. “I [shot a game] at a horrible location recently. The background, you almost couldn’t have made it worse. It was like putting a football stadium in a strip mall,” Strohmeyer says. “In cases like that, you shoot everything wide open and try to fill the frame up the best you can.”

Know Where the Action Is

If there’s one thing that’s more deeply embedded in Strohmeyer’s photographer DNA than being prepared, it’s knowing your beat. “People say to me often, ‘You know quite a bit about sports.’ I never thought of myself like that, but I guess it’s true,” he says.

After years immersed in sports, first as a student basketball player and then as a passionate, observant sports journalist, there just aren’t too many surprises. “Hockey I don’t profess to know quite as much about, but in basketball, I know how the players align, what side the action’s going to go to, where the isolation is, just because I know the game,” he says.

In a practical sense, this knowledge is your friend. “If a pitcher has a 95 or a 98 mile an hour fastball and there’s a right-handed hitter, he’s much more apt to push the ball to the right side of the infield. Who does a particular quarterback look for in critical situations? At a high school football game, how do you know where the ball is going to go? Find the biggest guy on the team—they’re going to run all their plays over to that guy. In high school and college basketball, most players are right-handed and still favor that side of the court. That helps you. All those little things help you figure out where to be and how to anticipate shots.”

And if you do miss something, all you need to do is wait, Strohmeyer advises. “My boss in my first job in Topeka, Kansas, would say, ‘If somebody does something once and you miss it, don’t worry about it too much, because chances are they’re going to do it again.’ I call this the rule of repeating action.”

Try A Different Perspective

Many iconic sports images show action on the field. But some of this shooter’s favorite shots are of moments off the field. Such opportunities make pictures that give a 360-degree view of the story.

“There are a lot of nuances in baseball, and you want to kind of have one eye open all the time,” Strohmeyer says. “[Former Boston Red Sox pitcher] Pedro Martinez was always kind of a joker, and as a starting pitcher, he was in the dugout all the time. At one game I remember looking over, and all of a sudden the other players were taping him to a post in the dugout with athletic tape. It was a hilarious picture, but you had to be paying attention.”

In the arena, remote set-ups can literally give another dimension to your shots. “I like basket-level pictures, because that’s the level the players play at. It gives you a different perspective,” Strohmeyer says. Shooting from directly above can give a photo a clean, high-contrast background and show the geometry of the game. “When the goalie bends over backwards to make a save, and he’s looking straight up in the air, that’s a great picture,” he says.

Remotes have to be approved by officials, and the rules vary by sport, league, and venue. “Most of the time it’s not a big deal, because it’s done fairly frequently, particularly in the NBA. Colleges, maybe not so much,” says Strohmeyer. “It’s a communication thing. There are a lot of considerations, the biggest of which is not interfering with play, but the main thing is to be above board with people and bring them into your concept. Get the people in the building to embrace the idea.”

Remember, You’re Shooting People

Under the padding, helmets, and face masks, athletes are humans, and that’s what fans want to see. How do you get behind the face mask? “Great athletes, great pictures” is one rule of thumb. “Some players just stand out. [Wide receiver] Randy Moss was always face-forward, and he made athletic plays,” Strohmeyer says. “He jumped high. He extended out.”

Also look for athletes—as well as fans, coaches, and officials—who face forward, with wide-open eyes and expressive faces. Part of that is the individuals; another factor is light. Even in auto racing, Strohmeyer says, “there are tracks where at certain times of day the light gets low enough you can actually see into the cockpit of the car.” Light shifts throughout the course of an event, and so should you: Shoot front-lit for a while, then backlit; if you’ve shot a lot of horizontals from the side, change it up by going deeper and longer. “There are all these evaluations you make about the types of photographs you want to take that go on constantly,” he says.

In the end, Strohmeyer says, “you’re trying to sum up the drama and the emotion of the sport. You want those pictures to have memory. And if you can do that, you’re going to be pretty successful, whether you’re shooting an ad campaign for Gatorade or a game for the local high school paper. If you can tell the stories in that manner, you’re going to be successful.”

ENTER OUR JULY SPORTS PHOTOGRAPHY CHALLENGE