Talking Books with Aperture’s Lesley A. Martin

The Publisher of Aperture's book division talks about the acquisition process, book publishing in general and two new fall titles.

Lesley A. Martin, who has been with Aperture off and on for the last ten years and has been executive editor of the book-publishing program for the past four, was recently promoted to Publisher. Her promotion was “reinforcement,” as she put it, that the revamping of the book-publishing program that she has spearheaded over recent years is a vital part of Aperture and its mission to be the premiere not-for-profit arts institution dedicated to advancing fine photography.

American Photo recently had the chance to speak with Martin to discuss her promotion, how she approaches the refined art of bookmaking, and the overall developments happening within Aperture offices on 27th Street in Manhattan’s burgeoning Chelsea district. But first, a look at two upcoming fall titles.

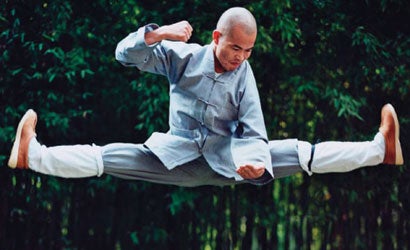

Shaolin: Temple of Zen, Justin Guariglia

Darius Himes: Ok, can we please talk about Shaolin: Temple of Zen. What an amazing project and book, on so many different levels! There are lots of very particular details that jump out at me about the book, let alone the amazing photography. Can you walk me through some of these details and the reasons behind them?

Lesley A. Martin: I loved working on this project. When I first started working with Justin, I knew he had an amazing story and some fantastic images, but it wasn’t immediately apparent how that book might be shaped. There was no maquette or any firm idea of shape or size or structure. So, we went back to the contact sheets. There are some books that come to us as very fleshed-out book dummies. This was a much rawer project.

DH: The cover is a flexibind with orange colored boards and the endpages are a very specific type of dusty blue. They offset each other so elegantly, as does the subtle image printed on the endpages.

LM: The orange and blue are meant to resonate with the saffron of the monk’s garb and the blue of his socks. The photographer was really obsessed with all of the details of Shaolin culture and with Zen. So we wanted to take the material — his photographs — that can be viewed in a fairly traditional documentary light and give it a new treatment, a new sensibility. The choice to use the uncoated paper was very important, because there is a very tactile quality to it that engages the senses. Justin’s work is grouped in a lot of different series, and so the question of how to present and structure and build the book around these series became important. We wanted to reveal a sense of what these monks dedicate their life to, and how their actions emanate from the spiritual core of their teachings. The book can be peeled back metaphorically like an onion and in the middle is a section of images that are printed on velum; there is a combination of texture and a conscious overlay of layers.

In this inner section of the book, the Kung fu action portrayed grows quieter and then you come to a section that shows hand symbols, all of which have very special meaning. We wanted the book to be about this documentary process and also about the phenomenal access to the historical temple that he was able to get. Shaolin monks and Kung fu have been such pop culture phenomena but you rarely have access to the real deal. I had a lot of fun sequencing in this book. It was a real challenge putting it together with Justin and the excellent designer we worked with, Lorraine Wild from Green Dragon, who also loved the subject matter.

DH: If I weren’t looking at this book, I would think, well, the subject matter is about movement, about Kung fu fighting, about an exterior and physical movement that has spiritual ramifications. How in the world do you convey that on an immobile, printed page?

LM: To me, the answer lies in creating a coherent core.

DH: Oh. Such a perfect answer! … Now, to get back to the secular world again, how do you see it in terms of its crossover potential and sales potential?

LM: We absolutely see it as something that will expand the audience for good photography. And sometimes that means working with subject matters that aren’t driven solely by the quality of the work, but that are also about what it is that they describe. There are all these other pop permutations of Kung fu, from video games, and the movie The Matrix, as well as the hip-hop group Wu Tang Clan. That’s all very cool. But this is one of the books that seems to have more crossover appeal. We want to find work that can hold its own as a really solid documentary photobook and that can appeal to many people including those people who haven’t known of Aperture before. As you can imagine, too, we are also enthusiastically promoting this book in Asia and elsewhere.

DH: What sort of text did you include?

LM: Mathew Polly, who has recently published a book about his experience in a Shaolin temple, contributes an essay, and the foreword is from the abbot of the temple. He gives a little context about what Shaolin is, and had some very nice things to say about Justin’s commitment to this topic, which he’s been covering for 8 years now. And then Matthew’s text talks about Shaolin practice and how it crosses these borders and how it has become international at this point. I think there are many different directions this book could have gone and one of them could have been something very quiet, such as a haiku on one page and an image of someone fighting on the opposite page. This could so easily veer into the area of the cliché. Instead, I’d like to think it is shaped in a way that is appropriate to the subject and still retains some of the rigor of a documentary project.

| © Hans Eijkelboom / Courtesy Aperture Books |

| Click photo to see more images from Paris-New York-Shanghai, by Hans Eijkelboom. |

Paris-New York-Shanghai, Hans Eijkelboom

DH: Ok. Let’s completely shift gears and talk about this book, which is actually three books in one. I’ve never seen anything like this!

LM: This is a very different type of project from Shaolin, where the photographer came with a fully realized maquette. As an artist, he has used the book format (like Hans Peter Feldman or Ed Ruscha) as a way of manifesting the work in its final form for many years now. So the question for us was really how to take something that was basically an artist’s book, but to turn it into something that we could mass-produce. It’s ingenious how you can fold out and do a comparative read of all three projects at once. And it is actually four books in one, because you have this little text booklet slipped in a pocket inside the front cover of the book.

DH: What is Eijkelboom up to here? The project is clearly typological in nature, and he is surveying people in these three major cities, correct?

LM: Yes. He has a long-standing history of creating these projects that are based on this kind of framework. So, for example, he’ll set out with a pretty basic idea: “I am going to go out today and ask people ‘who’s pretty and who’s ugly’ and I’ll take pictures of each and publish them in a book.” For the last 15 years (culminating in 2008) he has developed this idea of on-the-fly typology where he goes out in the street almost every day — five days a week — and he photographs based on these spontaneous frameworks.

He’ll photograph people that share a characteristic, such as a clothing style, or based on a type of bag they are carrying or what they’re doing. He has mainly shot in Holland, but for this project, which culminates a 15-year practice, he’s gone to Paris, New York, and Shanghai and has incorporated comparative landscape into this mix as well, which is relatively new for him. In this case, the grids aren’t based solely on the experience of a two-hour period, but built over months of activity and travel. The three cities represent a cultural era of sorts: Paris, which was the 19th century capital of the world, New York as the 20th century capital, and Shanghai as, possibly, the capital for the 21st century.

DH: You asked Martin Parr to contribute a foreword. What was his take on the project?

LM: Parr is very generous at pointing out talent in other people. We just knew that he would be somebody who could talk about the work — he already knew about it and loved it. Also, the text by Tony Godfrey is really wonderful and useful. He has written a great piece on the groundings of this body of work and of Eijkelboom’s work as a whole in conceptual art.

DH: And the Velcro in between the three segments?

LM: Well, you know, in the end, you don’t want the book falling off the bookshelf! We do have to be practical, too, after all.

Darius Himes: There have been several big changes and announcements over the summer at Aperture. Your promotion to publisher was one, as was the resignation of Ellen Harris, the Executive Director of Aperture, who had been with you for almost five years. Mixed in with those changes came the announcement of the Aperture Prize and a full list of summer activities in your rather new Chelsea space. How have all of these things affected Aperture?

Lesley A. Martin: The biggest, most impactful change starts with Ellen’s resignation. Obviously, losing one’s director is a big deal and creates a certain amount of turbulence no matter what. But from my perspective and that of my colleagues, we have been working very hard to build an organization that is stronger than ever, and we will continue to do so. Ellen did many significant things for Aperture that have helped establish a solid foundation for the growth of the organization as a whole. Now it’s up to us to keep it moving onward and upward.

Over the last year there had been a lot of discussion about how to move forward and define the book program. I would like to consider my new position as a reinforcement of the direction in which we’ve been taking the book program, it’s a reinforcement of the notion that quality and content is of the utmost concern to Aperture.

We’re very lucky to have a great team at Aperture — and it is very much a team effort here. We are at a point now where we can keep growing and moving forward. As of right now, the decisions the book program makes about which projects to publish will help set the agenda for the whole institution, so the decision making process is very consensus based. A project will usually begin with the book, but the work contained is then disseminated in different ways — online, in exhibitions, and promoted through lectures and book signings. And as each department works with the material, they each bring their own perspective to bear on it, allowing the material to move out into the world in different ways, and hopefully, to be seen as a multi-faceted body of work, which is always very satisfying.

We want to ensure that when we take something on, we can provide the best public platform for that project. The flip side of that is that each book project is scrutinized in multiple ways before we’ll acquire it — so it can take a while. But we take very seriously that the book program has to acquire projects that contribute to the overall mission of the organization. It begins with the book and then becomes the concern of the institution.

DH: You hint at the dissemination process involved for these projects and that it happens through various channels, such as exhibitions and online. But let’s talk for a minute about how the books are disseminated and distributed. In the last year, you began working with Distributed Art Publishers (D.A.P.), who is known as North America’s best art book distributor. What has that been like? Have they brought a new level of attention to Aperture books?

LM: Well, we work with D.A.P. in North America and Thames & Hudson overseas for the European and Asian markets — really the rest of the world. They are both phenomenally intelligent about art books. As Aperture positions itself and some of our activities in closer alliance to the art world, it means a lot to us to be able to find our books in more museums and the remaining independent bookstores. We’re excited about reaching broader audiences while still being able to keep in touch with our classic, core photo community.

DH: How does the acquisition process work?

LM: It is the editorial staff’s responsibility to ferret out projects from around the world that are of relevance to what’s happening in the photo world right now. We ask ourselves, what projects are advancing the conversation of contemporary photography in interesting ways, what is unique, what bodies of work have dropped off the radar that need to be resuscitated? We bring that to the table with a physical checklist of project criteria. We really want the work to contribute something new and innovative to the dialogue of photography.

And again, the actual acquisitions process is very much consensus-based. We look at each project to see how it will function in the overall Aperture mission, in all of the various ways that we ask a project to serve.

We’ve been asking ourselves: how do we differentiate ourselves from the great leagues of photobook publishers. It’s a very rich time for photobook publishing. For any project we take on, we have to be able to articulate very specifically what this book contributes to our list and our mission¬ — is there new ground being broken photographically; is the project of exemplary quality; does the project reveal something of historical, sociological, or conceptual importance? I’d like to think that we have been — and will continue to be — willing to take creative risks.

DH: You mention projects that “take risks.” How does that tie into concerns about the commercial success of a book?

LM: We consciously give ourselves leeway to do things that may not be major blockbusters.

DH: In other words, you are looking for success on more levels than simple commercial mass appeal, which to be honest is fleeting and never guaranteed anyway. At the end of the day, you want to be proud of the work and the book as a whole, not simply the bottom line of its financial success.

LM: Right. We have to feel that each book offers a contribution to the field in some way … That said, we’re also very conscious that we are a hybrid of sort — and that we function with the trade publishing world as a way of getting our books out there. We have to be savvy about that, but not to the extent that we start allowing the likes, dislikes, and various whims of the trade book business to dictate what we do.

DH: Who participates in these editorial meetings?

LM: This is actually in flux right now. Along with the creation of my new position, we have just hired a new associate editor — Joanna Lehan, who I’m very much looking forward to working with. Almost all of the editorial staff attend — from both the book program and the magazine, the sales and marketing team, our director of exhibitions and limited editions, and our development director. There is representation from all the different Aperture puzzle pieces. Each department thinks about how they could work with the material. There are always differences of opinions and grappling back and forth about each project. Is this project feasible at this time? How does it fit into the list of other books? Etc. That balance is really important. We’re not out to represent or to make an argument that any type of photography or particular genre is more important than the other — we just want to represent the best there is to offer from a broad range.

DH: You mention the “leagues of photobook publishers” out there, and indeed there really are dozens of interesting publishers right now. What is your personal perspective on publishing?

LM: Well, I come at publishing from a perspective that asks not just whether this particular body of work is great work, which naturally, has to be the starting point. But beyond that, one of the questions I ask is whether the work can function in an interesting way on the printed page. I love to talk to photographers about how they see their work being shaped into a book. And when I give lectures, I try to encourage people to be informed about books and what makes a good book, what they think a good book is, what are they looking for, etc. Personally, I get excited about minutiae and really enjoy speaking to photographers about book specifics: the kind of paper and binding, the format and trim size, how does it all fit together, what is going to make this book unique and different from the others. I really am a geek in that way!

–Darius Himes is editor of the photo-eye Booklist, and a writer and photographer. He lectures on photography at The College of Santa Fe and regularly talks to students and photographers around the country about photobooks.