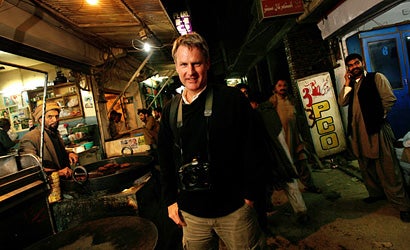

Behind the Lens with John Moore

Based in Islamabad, the Getty staffer shoots conflicts around the world.

The photographic community is incredibly diverse, made up of photographers that shoot from the sky to the sea and everywhere in between. Each month we look at a different segment of the industry, interviewing top professional photographers about life, their careers, and what sets their piece of the photographic industry apart from the rest.

This month we focus on John Moore, a senior staff photographer with Getty Images based in Islamabad, Pakistan. Before joining Getty, Moore was a staff photographer with the Associated Press, and was on a team that won the 2005 Pulitzer Prize in Breaking News Photography for their coverage of the war in Iraq. Having lived in Nicaragua, India, South Africa, Mexico, Egypt and Pakistan, as well as the United States, Moore estimates that he’s worked in over 80 countries throughout his career. Most recently named Magazine Photographer of the Year in POYi, Moore was awarded two first place prizes at the 2008 World Press Photo Contest for his coverage of Pakistani Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto’s assassination. Taking some time while on a layover in Johannesburg in route to Zimbabwe, Moore provides some insight into what it’s like to work as an international conflicts photographer.

Q. Where did you begin your career as a photojournalist? Did you work at a daily newspaper or were you shooting international conflicts from day one?

I actually paid for much of my university tuition by shooting sports – football, basketball, baseball – whatever assignments I could get and for whoever would pay, including the college newspaper and the Associated Press. I also took several paid internships at newspapers during my summer vacations while in college.

After graduation, the AP offered me a post as the photo stringer based in Managua, Nicaragua, and ever since I have worked internationally. Early on with the AP, I concentrated more on feature and social documentary photography. My first real experience with conflict photography was when I was sent to Somalia to cover the famine in late 1992. I was the only wire service photographer there when George Bush Sr. announced that the U.S. would send troops, so I had that important story to myself for almost a week until other photographers arrived. I stayed on through the U.S. invasion.

When photographing out on the streets of Mogadishu, I had two gunmen with AK-47s by my side at all times. After the U.S. Army said that we could no longer employ private security guards, I was out photographing one day and was robbed of all of my cameras by armed bandits and in a separate incident stoned by a mob a couple of hours later. Sixteen years and many conflict zones later, I still count those months in Somalia as the most dangerous of my career.

Q. You were recently the closest journalist to the blast during the assassination of Benazir Bhutto. Why did you decide to shoot the rally she was attending at the time?

The threat level against her, of course, was very high following the attack on her procession a few months before when she returned to Pakistan from 8 years in exile. During President Musharraf’s state of emergency, she had planned a large demonstration in Rawalpindi but was put under house arrest, so the rally didn’t happen. So, months later when the much-delayed event was finally to take place, I thought I should be there. And naturally we all knew there was a threat. In fact, the number of her supporters there was down significantly, as many people stayed home afraid.

Q. What was that experience like? Did you suffer any injuries? Are you happy with the images you captured?

I never expected her to leave the event standing up through the roof of her armored vehicle the way she did. I had been walking to my car, trying to leave the event, when I took one last look back and saw her riding along and waving to the crowd, which was swarming around the vehicle. Let me risk cliché and say – it all happened so fast – because it did. After sprinting back to her car, I only photographed her for 18 seconds, according to the time codes in the digital images, before I moved ahead of the vehicle just prior to the blast. Afterwards, I was temporarily deafened by the explosion, so for me it was all very quiet at first. It was almost dark, and I had not had time to raise the camera’s ISO to match the situation, so much of the photography was unusable because of very severe blur. That said, the movement visible in some of the frames probably added to the urgency of the photos. I suppose being so close to the blast, I was not really thinking much about shutter speeds. The possibility of a secondary suicide blast or just getting run over by Benazir’s fleeing vehicle was in mind, however.

Q. You’ve photographed in dangerous conditions throughout your career. Have you ever feared for your life? What drives you to continue documenting life and death in conflict zones?

No matter how long you’re in this business of conflict photography you will always feel fear. When you no longer feel it, then it’s time to get out. More important is what you do with that fear. If you calculate your risks based on your instincts and experience, then you can channel your fear to help focus on what is in front of the lens. That said, there are never any guarantees – and no, fortunately I have never been seriously injured.

Q. When photographing in Iraq, do you travel on your own or embedded with American troops? What are some advantages and disadvantages of traveling with American soldiers?

When in Iraq I can really only work while embedded with U.S. forces. The advantages are twofold. First, working with the forces provides some protection against those that would do me harm. Secondly, as embedded journalists we can get incredible access to frontline fighting, among many other stories only possible by close proximity to the military. An occasional disadvantage is that it is difficult to move from one embed to another with a different unit on short notice. For example, an offensive may kick off, but if the unit you are embedded with is not taking part in it, then you miss the whole event. Naturally, I would also like to cover the Iraq civilian side of the story, but, as a foreigner, the threat of kidnapping is just too high.

Q. As a photographer constantly on the move, are you able to spend much time with your family? Do you visit them in the United States or do they live overseas?

I live with my family in Islamabad, Pakistan, so I have been spending a lot more time with them recently, since Pakistan has slipped into such instability during the last year. I have been traveling less and covering more, for better or worse, closer to home. My wife, Gretchen Peters, is the correspondent for ABC News in Pakistan, so she understands well what I do for a living. Islamabad has remained fairly safe so far, despite the chaos in much of the country. Hopefully that will not change.

Q: What photography equipment do you use on a daily basis? Your cameras and lenses must be subject to some serious wear and tear, how often do you need to replace them?

I’ve used Canon for all my life, even before EOS, if you can imagine that. Currently I use two of the new generation Mark III bodies for news and a 5D for features. The first Mark III bodies to come out, as we all know, were disgracefully unsharp. Amazing how Canon threw away more than 15 years of professional competitive advantage over Nikon in a single blunder. That said, I think they will recover. It is healthy to again have good competition between Nikon and Canon.

For lenses, I usually use a 16-35mm f/2.8 and a 70-200mm f/2.8 for news and a 28mm f/1.8 and a 50mm f/1.8 more for features. I also have a midrange zoom and a 300mm f/2.8, both of which I use rarely. My backup zooms are a 20-35mm f/4 and a 70-200mm f/4 IS. I use flash with slave sometimes. Lately I have been doing a fair amount of multimedia, so I often carry a Canon HV-20 HDV camera and a Zoom H2 digital audio recorder.

My camera gear gets some serious wear and tear because of the environments I work in. You just barely knock a zoom lens against the armored door of a Humvee and the thing snaps in half. I keep a backup wide zoom when I am traveling, as well as my fixed wide lens. For repairs, sending gear out from Pakistan, as well as receiving repaired equipment, is a frequent problem, because of the impossible corruption and bureaucracy in the country’s customs office. Interestingly, the easiest place to pick up my repaired or new equipment has been Baghdad, where customs is not a problem and DHL is located just downstairs from our office at the Al Hamra Hotel.

Q: How do you transmit images to Getty Images from the field? What equipment do you use? Do you send all the images from a shoot or do you edit yourself and only send selects?

When in the field I often use a BGAN satellite transmitter. It connects to the internet and I then send my photos to the Getty server via ftp and check via Instant Messenger to see if they landed ok. It takes less than two minutes per photo, and I always send an edit, not the entire take. When you are often shooting at 10 frames per second, sending everything is not really an option. On any given day on assignment in the field, I may send between half a dozen and twenty photos, it just depends on the situation.

Q: Where do you spend your time off? Do you travel on vacation or do you spend your time resting at home?

When I am at home, I am rarely off. While I may not be shooting photos every day, I am usually lining up the next assignment, sending dozens of emails and spending time on the phone. The places I tend to work often require myriad logistical efforts to reach, so there is a lot of leg work that goes into the process. When I was with AP, I could often rely on the office staff to set up much of my logistics – air travel, translators, drivers, etc, but with Getty I am on my own out here and do it all myself. Plus, I spend a lot of time trying to keep up on the news and when possible, stay a bit ahead of it. We often vacation back at our parents’ homes in the states, so that they can get some time in with our two young daughters. It is hard for them, as grandparents, being so far away. This year we hope to also spend some vacation time in France and perhaps Thailand.

Q: How many countries have you worked in? Where are you shooting now? Do you receive much notice before it’s time to jump on a plane and head off to your next assignment?

I am not sure exactly how many countries I have worked in, but I think it is over 80. I have been posted and have lived in six – Nicaragua, India, South Africa, Mexico, Egypt and Pakistan. I just finished an assignment photographing Marines arriving to Kandahar, Afghanistan and am currently in Johannesburg in route to Zimbabwe. Most of my assignments are self-generated, so I often line up the timing myself. Naturally, plans are thwarted when we react to natural disasters, such as major earthquakes, storms, etc.

Q: Are there any photography or journalism related websites that you keep up with on a regular basis? Do you have any advice for aspiring journalists aching to join the elite ranks of war photographers?

I don’t keep up with any sites on a regular basis, although I think they are really good for the profession. Young photographers can always concentrate on stills as their passion, but should also learn video and audio and how to edit multimedia stories. With online journalism becoming more important every day, multimedia is certainly the future of our business. That said, the power and permanence of the still photograph is as strong as ever, and I don’t think that will ever change. As for being a war photographer, I don’t really consider myself one. It is very rare for the United States to be fighting two wars simultaneously, so I currently feel an obligation, for reasons both personal and historical, to be there. That said, a time will come when I am no longer involved in conflict photography, and I will embrace that change. Advice for aspiring photojournalists getting involved in war photography? Trust your instincts, calculate your risks and stay behind the guys with the guns.

Read other interviews from the Behind the Lens series

• June 2008: Robert Hanashiro

• May 2008: Steve Winter

• April 2008: Preston Gannaway

• February 2008: Martin Schoeller

• January 2008: Brian Skerry

• December 2007: Jasin Boland

• November 2007: Norm Barker

• October 2007: Cameron Davidson