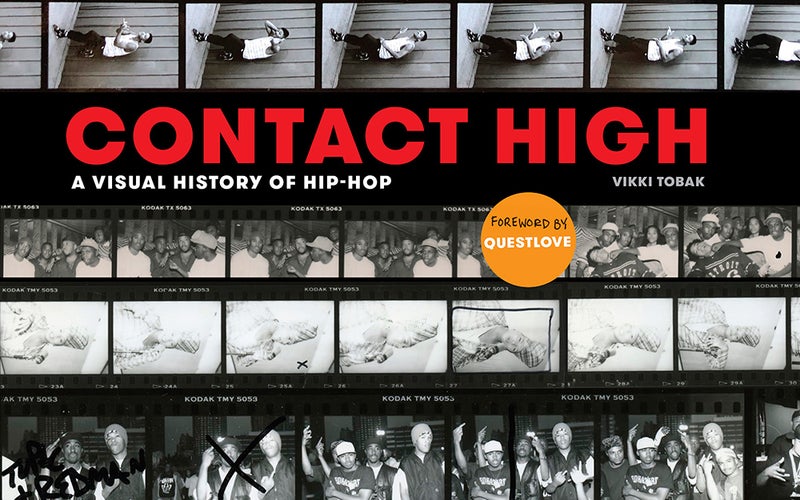

Photographers’ contact sheets celebrate the visual history of hip hop

Uncovering hidden gems and celebrated frames from hip hop’s 40 year history.

In the days before digital a contact sheet was one of the most important working documents for a photographer. The multi-image sheets get their name from the way in which they’re created: The negatives lay on top of a sheet of photographic paper and light from a darkroom enlarger exposes the paper creating mini versions of each photo on a roll of film. Looking at a contact sheet often reveals how a photographer was thinking and what it took to get the iconic shot that the public comes to know and love. These documents weren’t made with public consumption in mind, and often you’ll find them marked up with notes from the photographer and the subject.

Contact High is a new book from Vikki Tobak that celebrates the history of hip hop through these precious working documents. The book features over 100 outtakes from photoshoots spanning from 1979-2012, with interviews and essays from the photographers who shot them.

Contact High

The work will be on view at the Annenberg Space for Photography in April, and the book is available now.

We spoke with Tobak about the process of bringing these images together and the surprises she found along the way.

Did you know that there were specific images and contact sheets that you wanted to include in the book, or was the curation process more collaborative with the individual photographers?

My selection criteria was twofold. I knew there was certain images in hip hop’s collective consciousness that were must haves: Biggie in the crown, the Nas Illmatic photos, Lisa Leone’s Snoop photos. I started there. There were also certain photographers that had to be in the book, but I didn’t know exactly what images I wanted from them. There were certain photographers who dedicated themselves to documenting hip hop, for whatever reason they found it important really early on to point their camera at hip hop. I wanted to make sure that those photographers were celebrated in the book too, because they are as much a part of the culture as the artists and the djs. Jamel Shabazz was one, he is really well known, but I didn’t have a particular image in mind, he was just so instrumental and of the culture that he documented. I was thinking we would use one of his street portraits, but then he had an image that had been used as The Roots’ Undun cover.

Why were you interested in showing the contact sheets from this era?

I wanted a way to take people deeper into the story, a lot of times the sequence on a contact sheet will show you the neighborhood, the setting, certain friends, confidants or producers that were really important in the making of the artist’s careers—things that you don’t see in the main image. The contact sheet was a way to take you into a bigger story of what was happening in that moment and what was happening in the artist’s life at the time. A lot of the time in the contact sheet you will see these spaces that were really important in hip hop, especially in a lot of the early shoots. You see Skate Key Roller Rink, you see 52 Park which was a really important park in The Bronx where a lot of b-boys would congregate. You see neighborhoods. I thought that the contact sheets took you beyond the photo and took you into all of these other elements of what made the culture.

Were there any photographers that you had to really convince to release their contact sheets for the book?

Yes! Contact sheets are very private. They were never intended for public consumption and by showing them the photographer is showing you their mistakes, which can be a very vulnerable thing to do. Even though photographers love looking at each others contact sheets and it’s a really great way to nerd out, I think it was vulnerable for a lot of photographers. Glen E. Friedman was someone who I really had to convince. He has two shoots in the book: Public Enemy and Beastie Boys. During the Public Enemy shoot there was a lot of disagreements over the photo that was ultimately chosen—it wasn’t necessarily Glen’s first choice. On the contact sheet you can really see the one that he wanted. That is a lot to share, it’s a lot of process, that he hadn’t really shared with anyone before. That took a lot of talking and trust building with me to trust that I would do the story justice. Glen is meticulous about how his story is told and how his photos are represented. I totally respect that.

Most photographers were really excited about it because they were excited to see their colleagues’ contact sheets.

Did you find anything unexpected as you researched for the book?

One of the nicest surprises was this photoshoot from Al Pereira in 1993, there had been this very well known image of Biggie and Tupac together: Tupac is giving the middle finger and Biggie is wearing this Morehouse shirt and it was a very well known shot. That was one that I definitely knew that I wanted from Al, but I hadn’t seen the contact sheet. When he sent me the contact sheet and I was looking through it the last frames on the contact sheet had Nas on it.

Al hadn’t looked at this contact sheet since those years, he had scanned the famous Tupac and Biggie photo, but he hadn’t looked back at it. This was in 1993, a year before Illmatic was even released. Nas wasn’t famous. I didn’t realize that there had not been a photo in existence of Nas and Tupac together. I put it on our Instagram and the internet went nuts, people were claiming it was photoshopped, they didn’t believe it was a real photo. I got a text from an editor at Mass Appeal saying that Nas wanted to know if that photo was real, he was seeing it and was in disbelief. He had texted the guys at Mass Appeal to ask if it was real. I explained that it came from negatives and I had the original contact sheet—ten mins after I responded Nas put it on his Instagram.

For Nas that photo was a never-before seen photo with Tupac, who he had a very tumultuous history with, but it also had his very close friend who had died. Seeing how much these photos mean to the artists means a lot to me. This is their history. This is their family albums in many ways.

Were there any images that were difficult to track down? Frames that you knew that you wanted that photographer’s had lost ownership of?

If I had decided to do the book about contemporary hip hop photography I don’t even think I could. If you are going to photograph with Jay-Z or Beyonce, you aren’t going to own those photos. Today when you do a photoshoot with an artist they usually do a full buyout.

Related: Chris Sorensen’s clever portraits of celebrities and CEOs

Most of the photos that I wanted for the book were owned by the photographers, fully outright.

There were a couple instances where I had reached out for things and learned that the label had taken everything, like the Midnight Marauders photos for A Tribe Called Quest. There were a lot of paper trails where people didn’t know what had happened to certain photos or contracts.

Danny Hastings had very few negatives in his possession from the Wu Tang shoots because Sony had them—a month ago Sony found a bunch of Wu Tang archives and negatives. I was bummed that they didn’t find them in time for the book, but it speaks to the fact that there is a lot of material out there in old filing cabinets. For the most part everyone had ownership of their photos, just because it was the nature of the time that they were working in. Visuals are a lot more monitored now.

Back then they just needed one photo for an album cover, one photo for the press kit, a few here or there, and then that was it. Now, we live in this age of Instagram where images are just as key as the music and all the other materials. It’s a different day for sure.