Interview: Rick Smolan’s Journey Across the Outback

New interactive book brings together a National Geographic photographer’s vintage slides with film stills from _Tracks _

camels

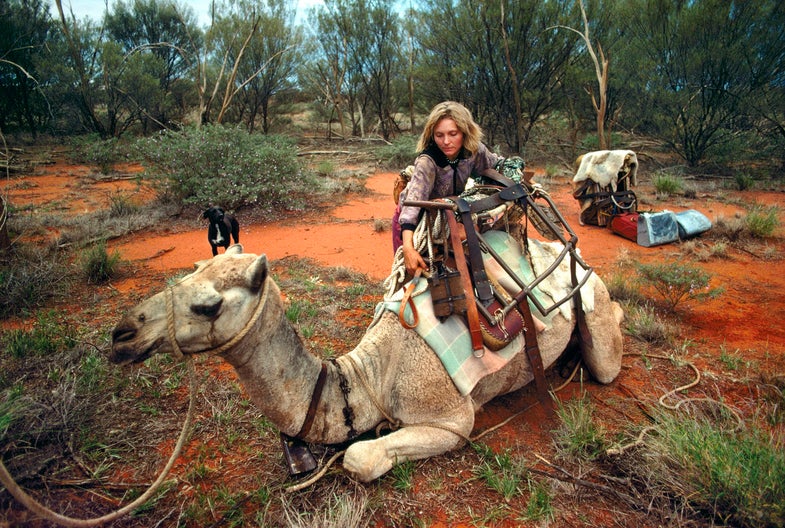

In 1977, National Geographic sent photographer Rick Smolan to document Robyn Davidson as she made a solo 1,700 mile trek across the Australian outback with four camels and her dog Diggity.

Smolan’s images and Davidson’s incredible story were originally published in the May 1978 issue of National Geographic. Davidson later published a book about her journey called Tracks, which this fall was adapted into a film by the same name starring Adam Driver and Mia Wasikowska.

Last month, Smolan released his own book, Inside Tracks, an interactive coffee table book that combines his original photographs from Davidson’s journey across the outback with the stills from the film.

Here, Smolan talks to Pop Photo about the amazing assignment he was handed as a 28-year-old, what it was like working with Davidson and how his journey through the outback changed his eye.

Your new book Inside Tracks makes it pretty clear that Robyn wasn’t exactly pleased to have a photographer documenting her journey for National Geographic, what was it like to take on this assignment?

I was sent off on this incredible journey with this woman who hated me. The moment I got out there she thought she had sold her soul to the devil. The beginning of the trip was pretty tense. Once I actually developed all the film and brought it out to show her… she looked gorgeous and the pictures were pretty wonderful and she said, “Don’t you make me look like a god damn model. You think I’m out here to pose for you?” It’s like no matter what I did I couldn’t win. It was the most interesting thought provoking, stressful, magical experience I’ve ever had.

I always had two reactions when I got assignments, especially the one with Robyn. The first was this is so cool and the second was this is an opportunity for me to screw up and regret this for the rest of my life. It was this double-edged sword of how great to have this chance and then what if I screw it up.

What were your impressions of the Australian outback when you first arrived to shoot Robyn’s story for National Geographic?

At first I thought Robyn was beautiful and the outback was ugly—it was a great backdrop, but she kept talking about look at the light, look at the plants. You can see the pictures start changing as you turn the pages. I just started seeing it through her eyes. Twilight lasted so long that you could shoot with Kodachrome 64, I just remember thinking sunset was an hour ago and I’m still shooting on 64 Kodachrome.

Aside from Robyn not particularly wanting you there, what other challenges did you face shooting in the Outback?

Shooting film, you don’t even know if the batch of film you bought is good to begin with. Then you are out there in the desert where it is incredibly hot. I had a cooler, to keep the film night temperature. The dust in Australia is the finest dust in the world and it gets into everything. The other problem that I had is Robyn didn’t wear clothes a lot, she insisted on walking around naked.

The rule if you worked for National Geographic is you have to send your film back undeveloped to them and they develop everything—they don’t want photographers to edit any of their own pictures. But I didn’t want to send my film back to them, for a lot of reasons, but the least of them I didn’t want them to think that what was going on was going on. I didn’t want to send pictures of this woman I was in love with naked to some guy in a suit sitting back for people to ogle at National Geographic. I would go back to Melbourne or Sydney to develop the film. I would edit it myself and then I would only send them frames I wanted them to see. You can imagine the first phone call: “This is your big opportunity, you are 28 years old and we are trusting you with a very big important assignment and you just broke the rule.” I still kept somewhere the telegrams I got: “You’ll never work for us again. You’ve broken your contract. Who do you think you are?”

Did the photographs you were trying to make change over the course of the trip?

Before this trip I was an okay photographer, but for Time that is all you need to be: F.8 and be there. You didn’t have to brilliant you had to be dependable. The other reason I developed my own pictures is how many pictures can you take of someone walking with a camel before its like the same picture with a slightly different background. It was going to be useless for me for them to say your film came out fine. I wanted to see what I hadn’t done. I wanted the feedback you get now by looking at the back of your camera.

_Aboriginal __children playing on a makeshift landing strip before the weekly mail plane arrives. **Photo: Rick Smolan**_

The bulk of the photos in Inside Tracks were never published in the original National Geographic story, were there any shots that surprised you as your dug through the slides to make the edit for the book?

The kids with the balloon. I had two cameras around my neck, one with Kodachrome and one with Tri-X—Tri-X was 400 ASA and Kodachrome was 25 during the day. I accidently put the Kodachrome in the Tri-X camera, so I shot that picture, and when I snapped the shutter, I knew it was one of the best photos I’d ever shot in my life. I knew it the moment I shot it. I loved the picture and then I looked down and realized that I was four stops underexposed, which Kodachrome is completely unforgiving—you’ve got half a stop at the most.

When I developed it was this dark sludgy thing—you could barely see it. In 1978 I put it in a safety deposit box and I thought someday, someone is going to invent a way to fix this. I was so heartbroken. With Photoshop we scanned it for the book and our Photoshop guy said, “_oh I can fix that.” _In a way the effect that we had to salvage it makes me love it even more. I can’t believe as a 28-year-old kid that I actually had the ware-with-all to actually think someday in the future some mad scientist will invent a way to save this picture.

Inside Tracks

Inside Tracks

Inside Tracks

Inside Tracks

Inside Tracks

Inside Tracks

Inside Tracks

Inside Tracks

Inside Tracks

Inside Tracks

Inside Tracks

Inside Tracks

Inside Tracks

Inside Tracks

Inside Tracks

Inside Tracks

Inside Tracks