Interview: Photographer Art Wolfe on Earth Is My Witness

The legendary landscape, wildlife, and cultural photographer explains the essence of his work

Art Wolfe

**Earth Is My Witness is a nearly 400-page book with more than 400 photos. It seems a statement of your career. Why this book, and why now? **

I met a publisher [Raoul Goff], and he said, “I would like to do your opus,” and I said, “What the hell is an opus?”

I think it was good timing. My career has been noted for variety, and it’s not the most prudent way to market oneself, if you’ve got subjects ranging from nudes to abstracts to culture to birds on a stick. [Goff] suggested a look back over 40 years, and so I started looking though the archives, and when I pulled out some of my historic best photos and compared them to anything I’m shooting today, they fell apart—the best and sharpest images just wouldn’t stand up. So rather than being a retrospective, this is really a look at these three genres [Desert/Savannah, Ocean /Islands, Tropical/Subtropical], many of which have been shot over the last two years.

So I’ve been running around the world upgrading the quality of the images, and in many cases shooting subjects I hadn’t even shot five years ago. I took it on as a brand-new project, not really looking back but looking forward.

In the book’s afterword, you say you’d like to photograph as many places and see as many things as you possibly can before your life ends. But I detected a sense of urgency.

When you’re in your thirties or forties your entire life seems ahead. I’ve never acted my age or felt my age. But yet, it’s inevitable that in your sixties, you realize, even in the best of circumstances, there are probably 20 years of travel left. So there is that sense that there is a limited amount of time to do what you want to do.

_**But it goes beyond that. In that afterword you also express an obligation to get out there and photograph. **_

Absolutely. In my seminars I’m as much an evangelist on stage as trying to teach—it’s really teaching life, and living the passion. Then, if you are in fact contributing to the greater society, there is an obligation to highlight stories that need to be told. And to bring insight and inspiration to other people.

Some say that beautiful pictures of landscapes and animals and indigenous cultures are essentially a form of nostalgia—that it’s all going to be over very soon, and that there is fundamentally no point to it, other than making pretty pictures. How would you respond?

I think that those people who say things like that would probably say that not only about photography but also a litany of other subjects. They are the doubters, the downers.

I could respond in many ways. One point is that there are photographers who are journalists, who are documenting the degradation. I also think that you can inspire, and win someone’s interest, through a positive image as well. I happen to shoot both, but inspiring people through a positive story is probably even more effective than showing the destruction.

The other point is that there are so many positive stories out there that we fail to hear about. We tend to hear the sensational headlines—those things command attention. But there are more eagles in Seattle than there ever have been. They are nesting in every city park. There are more mountain lions in America now than there have been probably in the last hundred years.

And there are cultures to this day that have never had Western contact. There is an organization in the Amazon whose job is to protect indigenous cultures. There are shots that I took 25 years ago that I could never replicate today, because maybe that tribe has changed or, more likely, you can’t even get into these tribes today because they are being protected by organizations.

Whether we have the capacity to thwart all the ills that could face human beings, that’s something that you won’t rally support for by saying,“What’s the use?” Let’s roll up our sleeves and see what we can do.

You describe yourself as a cultural photographer, as opposed to a landscape or a wildlife or a nature photographer. What was the a-ha moment for that?

I was on the first Western expedition into Tibet, by invitation of the Chinese government, in 1984. I took the opportunity to go to this forbidden kingdom. While I was there, I put more interest in the people, the tribes, the mountain villagers, than even photographing Mount Everest and the beautiful land. I remember seeing, in a small town called Shegar, people cramming their heads into a tiny building to watch a black-and-white TV, and it was like they were staring into the light of a train coming their way. And I said, “When I come off this mountain, I want to go to places where tradition is still intact.” Shortly thereafter I started work on a book called Endangered People.

At what point did you go digital?

I went digital exactly when my colleagues told me it’s on par with film. I went on a trip to Antarctica, when the first Canon 12-megapixel full-frame camera came out [the EOS-1Ds]. I got one, went with that plus 500 rolls of film with my film camera and a little laptop—I had never used a computer prior to that.

Leaving South America onto the Drake Passage, I went outside on the boat and I took a picture with the digital camera, just to see what the exposure would look like, brought it back and figured out how to download it onto the computer, and up it came. I saw that and realized I had shot it five minutes before. I have never shot a single exposure of film since. It was like a meat cleaver coming down. It was that immediacy that really connected with me. There was no longing or looking back toward film. It was about “How can I take better pictures and be more efficient?” and digital was just that.

Earth Is My Witness, his 17th book, is due from Insight Editions in October with a list price of $95.

It’s astonishing how many older people who fell away from photography have come back because of digital.

My audiences in seminars are generally between 40 and 70, some even older. And I say congratulate yourself: You’ve got an interest in photography; now make that interest a passion—love it, drink it, and you will live a longer life. People who think, who are creating, who are passionate, tend to live longer. I’m like a role model for the retired set.

How do you put up with all the travel and the usual hassles involved—luggage getting lost, cameras getting lost?

Drugs and alcohol [laughter]. All those flights, getting delayed, it’s part of the business. I cannot just put brakes on and decide I want to retire—I can’t afford to do it, nor would I want to—but boy, the psychology of getting through all those lines and all those delays and all the nonsense of world-travel people… If there were an easier way for me, I would do it. But I don’t have that luxury.

That transporter on the Enterprise…

My god, wouldn’t that be sweet!

Art Wolfe is an award-winning photographer based in Seattle.

Women of Thar Desert

Active Volcano

Humpback Whale, Vava’u, Tonga

Halema’uma’u, Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park, Hawaii, USA

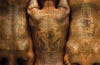

Chimbu Men

Cheetahs