A Brief History of Photokina: The World’s Biggest Camera Tradeshow

A look back at the long and quirky history of what happens when the photography world convenes in Germany

There is an old Tibetan saying, “A thousand monks, a thousand religions.” You could say something similar about Photokina, “A thousand reporters, a thousand photo-shows.” It is so vast and so diffuse, and it has changed so much over the years, that it is impossible to describe it fully.

From 1990 to 2012, my wife Frances Schultz and I reported every single Photokina together. We were also there in 1982 and 1984. Of course we sat down together for a meal at the end of the day, and of course we talked about what we’d seen. Sometimes it seemed as if we had been attending two different shows. Ask anyone who has been there often and you’ll get endless anecdotes, snapshots, funny stories and rueful shakings of the head, all tied together with whatever narrative they have been able to assemble to try to make sense of their experiences.

Which is not always a great deal. Of sense, that is. Experience is another matter. On the Agfa stand in the 1990s, a skilled make-up artist was “dressing” completely nude girls with greasepaint. He literally painted clothes onto them: shirts, jeans, dresses.

Or: huge serried ranks of very expensive telephoto lenses, on a raked stand, for visitors to try. No, you couldn’t see the nude Agfa girls from there.

Of course the Agfa stand was very public: the public were six to ten deep. Some other stands were fortresses girt with walls, no admission except to the trade. Entrances were guarded by locally-hired security with no knowledge of, or interest in, anything except keeping people out. They are widely referred to as “road bumps”. Suddenly, easy reporting turns into investigative journalism.

One year, on the last day of the show, I was reduced to saying to the road-bump “You know, I don’t have to report the stuff you’re launching here. I can always say that the company in question probably had some good new stuff but couldn’t be bothered to tell me what it was.” Five minutes later I was talking to one of their national vice-presidents. That was one of the worst years for the fortresses, the year that my wife Frances Schultz wrote (you can guess the tune):

Don’t cry for me, Photokina,

For I am ordinary, unimportant

I don’t need pictures, or press releases

I’ll get my story

Without assistance

Then again, it is not just the press who receive strange and sometimes inexplicable treatment. One of our friends, a US camera manufacturer and distributor, wanted to import a line of Japanese lenses. “No,” he was told, “These are available only in Japan.” Being persistent, he asked to see the road-bump’s superior. Then the road-bump’s superior’s superior. Who told him that the lenses were available only in Japan, and that if the would-be importer didn’t go away, the manufacturer would call the police.

All this is probably because Photokina has never quite figured out what it wants to be. Like a human being, it has sometimes lost its way and taken wrong turnings. In its adolescence it said all the usual things: “I didn’t ASK to be born”, and “This is REALLY unfair!” Even at 33, it is still changing, still unsure of itself. At 33? Yes. The year 2014 sees the 33rd Photokina: it’s a bit like a child born on February 29, so it doesn’t get a birthday every year.

The show started in May 1950 as a showcase for German cameras plus an international photography exhibition: the latter a bit like today’s Rencontres at Arles in the south of France. In 1951, this time in April, it went international: only 70 foreign firms, as compared with 270 from Germany, but a harbinger of things to come. There was also an international color film convention: conferences became another aspect of the fair alongside the trade show and public day out for enthusiast photographers. Seminars came later: they varied (and continue to vary) between invaluable insider tips from top professionals; ego trips from has-beens; and naked commercial promotion of products of widely differing usefulness.

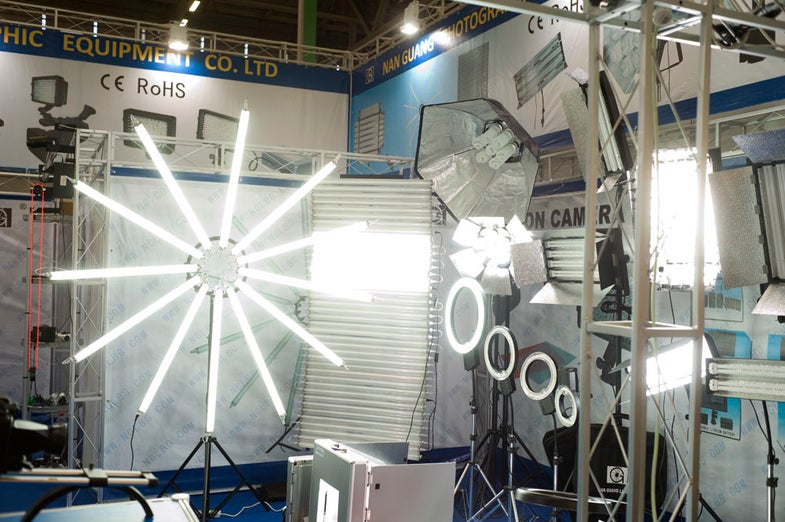

April 1952 saw the third and final annual photokina: it went biennial. At least for a while. Spring for ’54, then autumn for ’56, ’58 and ’60. Then bigger gaps: March ’63 and October ’66. The latter saw the first International Convention for Photography and Cinematography in Industry and Technology, which is probably a maximum of three words in German. Only after ’66 did it settle down to autumn in even-numbered years, the pattern we know today. But different products come and go; the emphasis changes. In 1986 they introduced Professional Media, whole halls dedicated to things such Klieg lights, follow spots, even cinema seats. Well before that, there was a lot of sound equipment too: tape recorders, for example, which first appeared at Photokina 1958, replacing the old wire recorders.

In ’68 the three reserved half-days for the trade was stretched to three whole days, as a result of which attendance dropped from almost 200,000 to 182,000. In ’74 it became a trade show only, with the art exhibits moved outside the exhibition halls so that the public could see them. That year they got just 95,000 trade visitors. Not until 1988 would they go back to letting the amateurs in – and then, only to the “amateur” halls, 1-8, and not for the whole show. Nowadays, there are no real professional/amateur distinctions, though few amateurs are likely to be excited by whole hall full of photo albums.

Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that there are fifty stands that really interest you. First you have to find them. Not easy: Photokina is huge. Once you do, you may be received with anything from complete indifference to red-hot enthusiasm. For the former, there are plenty of road-bumps who hand you a CD and say “It’s all on there”. Then they look puzzled when you say, “Why would I come all the way to Photokina to pick up a CD?”

By contrast, one highly-placed research scientist at Konica used to delight in explaining technical details to anyone who could understand, with the aid of graphs and charts and research papers. Frances cultivated people like that, which is how (for example) she learned about developer inhibitor release mechanisms (DIRs) in high-pH color developers from one of her chums at Kodak and associated fourth-layer film technology.

This sounds highly technical, and it is; but it is one of the reasons why magazines used to send their best journalists to the show, in large numbers: people who understood the subject, and could listen. The trick was (and still is) getting behind the scenes. Perhaps surprisingly, there are relatively few important introductions at Photokina, though of course there are spectacular exceptions.

Leicas wearing their fancy party hats before the unveil

Leica, in particular, managed to keep the S2 (Photokina 2010) a complete secret, and although there was a great deal of speculation about the M (typ 240, Photokina 2012) they made a truly spectacular launch. At the launch party, not only was Nick Ut, author of the famous “napalm girl” picture, there: so was the girl herself, Kim Phuc. By then she was a woman in early middle age (sorry, Kim), promoting her foundation for the child victims of war, www.kimfoundation.com. As she said, “For years, I felt as if that photograph controlled me. Now, I feel that I control it.”

It may seem odd to be so dismissive of equipment introductions, but the truth is that when you look back, yes, they were great at the time, but they have all blurred together over the intervening years. The Leica was introduced at the Leipzig Spring Fair in 1925 and E. Leitz were already onto the IIIc before the first Photokina in 1950 – which was the year the IIIf was introduced. The IIIf had numerous advantages over the IIIc, including a stronger, die-cast body and flash synchronization, but at 64 years remove, it pales next to the M3 (1954, at Photokina, naturally).

But the M2 appeared in 1957, a non-Photokina year, and although the Hasselblad SWC was one of the first products the company showed at Photokina (the other was the 1000F, introduced in 1953) the seemingly immortal 500C was another 1957 introduction. The Pentax appeared in prototype form at a Japanese show in 1954 (and incorporated absolutely no completely novel features, though it put together several existing features in a sublimely attractive package) but did not actually enter production until, yes, yet again, 1957. And the Nikon F appeared in April 1959. For that matter, the Rolleiflex was introduced in 1928, but apart from collectors, who now knows (or cares) the years of introduction of the D, E, F and G versions?

The Nikon EM, from the era when SLRs were still small

Also, things happen slowly and across the board. Sometime in the 1990s, SLRs started to get more and more bloated, a far cry from the slim elegance of a Pentax SV or even a Nikkormat. I made no friends with manufacturers when I said, “I prefer smaller, lighter cameras, so I’ll stick with medium format.” But who remembers (or cares) exactly when which bloated camera appeared?

Some of the most important innovations were the least hyped. Some, like the DIRs mentioned above, were hard to understand, but DIRs allowed cleaner, brighter colors and were especially useful with fast films. This sort of stuff is easy to skip, but it’s important, and it’s a lot less widely reported than some new “flagship” SLR. You don’t go to Photokina for the easy stuff, the stuff that will be heavily advertised. You go for the arcane stuff, the interesting stuff, the stuff that won’t be widely reported. You go for the mood, and for what’s really new, not just the latest “upgrade”.

For an example of “really new”, at Photokina 1996 a newly-revived Alpa showed a frankly strange hybrid with a modified Hasselblad lens on it: so heavily modified that it would no longer work on a Hasselblad. There were just two people on the stand: Thomas and his wife Ursula. Most journalists either failed to mention the Alpa, or dismissed it. I was one of the few that saw a possible future for the company. I was right. Their next model was the 12-series, with and without shift (12 S/WA and 12 WA). These and their variants are still in production, and selling very well indeed: as well as you could possibly expect from a staggeringly expensive Swiss-made camera, one that makes a Leica seem modestly priced. I remember Thomas saying “If we sell 50, we will break even. If we sell 100, we will make a profit. If we sell 200, we shall be very happy indeed.” The size of their stand at modern Photokinas and the number of staff on it suggests that they are very happy indeed.

A picture of the Alpa 12 final version next to the prototype

This is an important aspect of Photokina: meeting people. When you can discuss lens design with the world’s leading lens designers, you learn all sorts of things about the trade-offs that are inherent in lens design – and you also learn that “it doesn’t matter how many computer models and simulations you do, you’ll never know exactly how a lens is going to perform until you make it” (Dr. Nasse, Zeiss).

You learn the sheer romance behind some companies: not just the literal romance between Thomas and Ursula, long-married proprietors of Alpa Capaul and Weber, but the romance of how they wanted to make something truly and greatly Swiss, and therefore decided to make the 12-series Alpa. Or of course you can find yourself having dinner in a small, cheap Greek Imbißstube with two thoroughly charming people from American Photo/Pop Photo.

We talked about what we’d seen, and what we thought about it. Surprisingly many reporters don’t seem to do this. They just gather press releases; rewrite them; and assume they have done their job. One even took the last day of the show off, to go shopping, because she was sure she had gathered all the information she needed. Actually understanding what is happening requires a bit more effort, a bit more hunting among the more recondite booths, a bit more talking to fellow enthusiasts rather than to the PR flacks and road bumps and time-servers.{C}

Visiting Photokina is much like gold mining: there is a lot of rock surrounding the gold. The knowledgeable people, the true enthusiasts, the innovators, the entrepreneurs: they are all there. But you have to track them down, winnow them out. Sometimes, too, you have to cultivate them over several Photokinas. Some are afraid of having their ideas stolen. Others just don’t speak very much English. Or German. Or French. Or Italian. Or any language other than their own. Anyone reporting on Photokina should at least be able to read enough German to get the gist of a press release in that language, and ideally to understand (and speak) a little German too: “Verlangsamt, bitte!” (Slowly, please!). You can generally find someone who speaks some English, eventually, but it’s always a lot easier if you speak even a few words of their language and understand a tiny bit about their culture.

On the subject of culture, I recall a very dear friend, slightly pie-eyed, regaling several of us with all that he had learned from the Soviet stand. Yes: it was that long ago. We were lost in admiration: “How did you find out all that?” He replied, “It was simple. I plied them with their own vodka.” As former journalist Sir Terry Pratchett put it, journalists drink twice as much as anyone else, and for twice as long. You may not approve. Our vodka-swigging chum has now given up entirely. But consider the simple truth that after a few drinks, most people share more. “Have you seen….?” “What do you think of the new…?” “Do you really believe that…?” A journalist’s job is to find things out, and where possible to make sense of them. It is not merely to regurgitate what press releases want them to believe.

Good luck

Of course it’s possible to misread the mood, or to fall for ideas that are not, in retrospect, all that good. In 1952 Viewmaster stereo was a big hit. You need to be quite old now to remember the brown Bakelite viewers and their disks of tiny stereo pairs, let alone the weird cameras with their slanted, offset film track. Or what about 70mm? Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, this was touted as delivering the speed and convenience of 35mm (typically with 53 6x7cm exposures on a roll) with the quality of roll-film. In retrospect, it is clear that most people wanted either the convenience and low cost of 35mm, or the quality of medium format: 70mm was a compromise that very few needed. The main exceptions were museums, who needed large quantities of high quality images and often used Linhofs. Famously, too, NASA favored 70mm thin-base film in their Hasselblads for both lunar and non-lunar missions.

For that matter there are technologies that were invaluable, but have been superseded. Peel-apart Polaroid was one of the great hits of the first ever Photokina in 1950, having been introduced in the United States in November 1947. In the 1980s and 1990s Polaroid always had a whole (small) hall to themselves, and their dinners were legendary, but they were destroyed by digital imaging in the early 21st century. Few amateurs ever realized just how much Polaroid was exposed professionally, whether for mundane applications such as recording oscilloscope traces or for checking exposure, composition and content (no exposure meters left in shot) when shooting color transparencies.

There are also cameras that hardly anyone has ever heard about. Admittedly I heard the story of the Tessina at second hand, but it ties in with everything else I know about both photography and military intelligence. It used standard 35mm film in special cassettes, delivering a 14x21mm laterally-reversed negative. Despite being a twin-lens reflex (!), with motor drive (!!) it was tiny: small enough to mount on a wrist strap and hide under a generous, well-cut shirt cuff, though it was still rather bigger than even a cheap diver’s watch. It would also fit inside a cigarette packet.

Although according to several reports it was introduced in the fateful year of 1957, the history dates from a later Photokina: possibly 1958, more likely 1960. At the show there were only a few inquiries. The owner of the company was convinced that he had a failure on his hands. But when he got home, his front door was hard to open. A drift of letters had accumulated behind it, from various air attachés, naval attachés, innocuous-sounding government departments… The White House “plumbers” were reputedly among the later customers.

The tiny Tessina (Image: WikiCommons)

A friend who sold Tessinas as late as the 1990s reckoned that whenever the manufacturer got a reasonable sized order from whatever security organization was running low, he’d contact his other regular commercial vendors and ask how many they wanted before making an appropriate-sized batch. The Tessina was the camera of choice for the discerning spy for decades, and no wonder, given the 294 sq. mm. negative, over three times the size of the 8x11mm Minox negative.

In a more widely appreciated field, 4×5 inch cameras, 1992 was a great year, as it saw both the Toho FC45A, a ridiculously light full-movement monorail that weighed around 2 lb., and the Gandolfi Variant, which in its Level III form was one of the heaviest 4×5 inch field cameras ever built: about four times the weight of the Toho. Then again, it had movements that could put most monorails to shame and also accepted interchangeable backs for 5×7 and 8×10 inch. Sure, Linhofs and Sinars remained the standards against which commercial studio cameras were judged. But for some applications, the Toho and the Gandolfi were simply better.{C}

Then there’s the stuff that’s frankly dull. The point of a trade show is for manufacturers to sell things to wholesalers. Some of it is cheap junk: tripods stamped from paper-thin metal, flash heads that will fry your fingertips. Some of it is designed for the mass market, and is of little or no interest to the enthusiast. Remember the sub-miniature craze of the 1950s and 60s? 126 Instamatic (1963)? 110 (1972)? Disc (1982)? APS (1996)? Although these are often remembered as failures today, they weren’t: they sold a lot of cameras and a lot of film, though admittedly in most cases to the undiscerning.

Proportionately, they were way overrepresented at Photokina. But even then, among the junk, there were still some really interesting cameras, sometimes from major manufacturers Most were however complete commercial failures because they missed the point that there is usually a considerable gulf between those who want convenience, and those who want quality.

Again and again, as I was making the trip down memory lane that was writing this article, I realized that for nine out of ten photographers, it wasn’t the Big Introductions that made it worth visiting Photokina. No: it was the sheer joy of finding exactly what you wanted, or quite often actually needed, no matter how specialized or even frankly weird your demands might be. Monster field cameras in formats up to 20×24 inch, some of them absurdly lightweight like Keith Canham’s. Nikon SLRs sawed in half and then magically reassembled to create stereo cameras. A motor wind for your Hasselblad from Apcam in Indonesia. New Leica screw-mount lenses before Hirofume Kobayashi ever revived the Voigtländer name. Brilliant neoprene camera cases and straps and lens protectors from OpTech USA – and, as the name suggests, made in the USA too. Chinese 120 cameras with red-window film counting in 6x0cm, 6x12cm, 6x17cm and even 6×24 cm. Simple, rugged 4×5 inch cameras with no movements and a fixed lens in a helical mount, perfect for hand holding. Pinholes.

It’s all about doing it right, not about doing it for a mass market where price alone rules. That’s what “enthusiast” means, and it’s why companies like Linhof and Alpa and Zorkendorfer and Novoflex and Kienzle and Redged exist. Redged, for example, asked several Chinese manufacturers for tenders for the manufacture of their excellent tripods. Then, when they’d got a good price, they didn’t ask for a further reduction. Instead they said, “If we gave you 10% more, how much better could you make it?”

We’ll be a bit surprised to see any of these at this year’s show

Attentive readers may have noticed that a couple of paragraphs back I used the past tense: “made” it worth while, not “make”. How, then, have things changed? There are at least two answers: barriers to entry, as introduced by digital photography, and the internet. The former affects everyone. The latter affects mainly journalists, like me, and the sort of show coverage you get to read; at which point, of course, it affects you too.{C}

Barriers to entry are easy to understand. How much money and technology do you need to start a new company in the market of your choice? Think of a large format film camera. Basically it is just a device for holding a film holder and a lens the right distance apart. Any good wood-worker can make one. Film cameras are only a little more complex, especially if you buy in lenses and even shutters, as Rolleiflex did with their TLRs. Microscope manufacturers such as Ernst Leitz or Olympus could fairly easily move into camera production; cunning artificers made countless accessories in backstreet workshops. But to make a DSLR you need imaging chips and processing chips and custom software and almost unimaginable precision. The small company with a few bright ideas just cannot compete with the well established big boys, at least in the mass market. As a result there are ever fewer small companies at Photokina, and enthusiasts are increasingly replaced with corporate vendors of consumer electronics.

All of this is a strong argument for going to Photokina in person, as an enthusiastic photographer, rather than for going there as a journalist. My “dream assignment” would be to go as a paid amateur, with a brief to report on whatever interested me, after I’d had time to think about it and digest it. There’d be particular emphasis on the smaller companies, the less usual products, the people who march to a different drum. If we don’t encourage them, we’ll lose them. Of course I’d want to be there with my darling Frances, who would no doubt spot things that were completely different from what I saw: she’s one of the few people I know who actually care about camera bags and how they are made, let alone tripods. Then we’d write it up together as if we were talking to you, our readers, describing what we’d seen in the same way we’d tell an old friend about it. So if you can’t make it to next Photokina, let us know how many words you’d like to read in October 2016.