Ruth Fremson: Capturing History and Heroism

An oral history of September 11, 2001, as told by the photographers who covered the terrorist attacks on America.

“I thought, ‘No way, I’m not going to get buried.'”

A staff photographer for the New York Times, Fremson has worked in the Middle East and elsewhere. She is now based in New York City.

When the attack happened, I was at a polling place in Flushing, Queens [covering] the mayoral primary. My cell phone went off. It was my sister calling from Washington, asking me if I was at the World Trade Center. I said, “No, why?” She said that a plane had just hit it. I hung up and started running out the door. My pager went off, and that was the office calling to tell me that a plane had hit the World Trade Center and to start heading over there. It was rush hour. I was never going to get there on time, but I was [near] LaGuardia Airport. I called the office and said, “Why don’t we arrange a helicopter and do aerials?” They said okay and to head to the airport. I got there in about five minutes, but by this time I heard on the radio that the airspace had been sealed. I could see the skyline from the road, so I pulled over to take a picture and called the office, told them the airspace was sealed, and asked what I should do. So they said go to Brooklyn and see the view.

At this point I saw a caravan of police vehicles and ambulances [going toward Manhattan], and I attached myself to it. I was listening to the radio. There was an eyewitness talking about how he saw the first plane hit, and as he’s talking he says, “Here comes another plane — here comes another plane!” So I’m following the caravan, and as the [police] start to close the bridges [from Queens into Manhattan], they flagged the [caravan] through. I just followed and waved my press badge, for what it was worth, so they didn’t think I was something I wasn’t.

We went straight down to the corner of Vesey and Church Streets. There were cops directing the traffic, and they told me to park on Church [Street] so there was room for emergency vehicles. So I parked and saw the two buildings on fire. People were evacuating them, and police were escorting wounded people. That’s when I started shooting.

There were ambulances parked everywhere, bloody people everywhere. There was a woman who was sitting on a curb, breathing through an inhaler. And there was a nurse, crouched down behind her, hugging her, and every five feet there was somebody sitting there, head in their hands or looking up petrified at the building. There was a man in a suit on a stretcher, covered in dust and blood. There was a little tiny woman shaking, sitting on the curb completely covered in blood, being evaluated by emergency workers.

I saw firemen carrying people out, police with people over their shoulders. People running, people screaming, people looking up in the air, and people walking like it was any other day. I was concentrating on shooting the people being helped. It must have been five minutes later when the building collapsed. I heard this rumbling, which I thought was a third plane, because it sounded like it. So I looked through the viewfinder to see the plane, but instead I saw the building coming apart.

I took away the camera and saw people running and screaming and panicking. I thought, “Okay, let’s try and stay calm,” but then I saw the police and emergency workers running, and I started running too.

Some people were running into the subway station right there, and I thought, “No way, I’m not going to get buried alive.” I thought, “Mailbox…not big enough, fire hydrant…not big enough.” And I could just feel this tidal wave behind me. As I turned the corner there was a bookstore. I saw something — it registered that it was a police officer, and he rolled under a van, so I went under it with him, and at that moment the cloud came over us. It was black, and you couldn’t see and you couldn’t breathe. I held on to his arm or leg, I don’t know. But I thought we would just get crushed under there with all the stuff blowing around. But then it got quieter, and he started talking, so I said hello and told him who I was. At that point I realized that even though I was breathing all this crap, I was still breathing and moving and that I was fine.

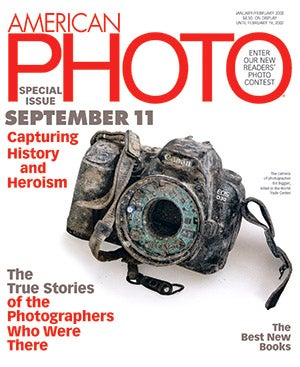

We heard glass breaking and then someone saying hello, and I don’t know if it was because I had so much soot in my ears, but it was quiet. I thought, “Someone needs help, and we’ll never be able to find them,” because you couldn’t see anything; it was still all black. There was a deli across the street. Inside there was a handful of people, some firemen and cops, everyone covered head to toe in white dust, soot. Miraculously, everyone seemed okay — physically okay, but shocked. We started taking the water from the deli to wipe our faces and clean our eyes, helping each other. Wiping the cameras off — that was amazing, just to get the cameras clean.

I started taking pictures of everyone in the deli with me. The cop catching his breath, a young woman who was petrified, trying to call her parents because the phones still worked. The phone was ringing, and it was someone looking for the owner, who wasn’t there. I called the office and told them I was okay, that I took some pictures, and that the first building had come down. I said, “I’m here, we’ll see what happens with the next one.” But I couldn’t go outside because it was still black.

Then it started to get lighter, so I went outside, and it was like it was covered with snow. I mean everything was covered in ash and debris and paper. I started taking pictures of cops coming in, going out. Police had shotguns.

And the rumbling started again. It was the second building, and everyone went running and screaming back into the deli. I hadn’t gone far, because a cop had said the other building would fall. We ran to the back of the deli, toward the basement, and it just got black again outside. You couldn’t see inside the deli, except for the glow of the bologna case.?Smoke was coming from the basement as well. I don’t know if something was burning down there, but it was coming from the vents.

One of the cops said we had to get out of there, and he called someone on the radio and said he had eight people with him and they needed to be evacuated. But we couldn’t wait for someone to come because it seemed way too unsteady in there. We got rags and we poured water on [them] and we held hands. We all started heading out toward Broadway. And at that point I took some photographs as the dust settled. I was just shooting the scene on Broad- way, the people walking around, the exodus of people walking across the Brooklyn Bridge.

I ran into another photographer and said I would go look at City Hall and she would stay there. I took some pictures and started walking around to my car, but they wouldn’t let me get it because it was too close [to Ground Zero]. Then I started walking back to the office. The streets were just full of people, and no cars. I got to Times Square and then came into the office.

I [used to be] based in Jerusalem. I’ve covered bombings, but they were suicide bombers blowing themselves up in a market. This [story] is bigger than anything that I’ve ever covered. To see destruction on a massive scale isn’t shocking to me, but to be right there at the moment when so many people were destroyed….

The people that I was in the deli with, that period of time when the buildings came down, and the policeman that was under the van with me will always be with me. The wife of the policeman in the picture I took, bending over, she e-mailed me and told me that he was fine. That was an incredible feeling for me to know that he was okay.