Heroes of Photography: Joseph Rodriguez

Committed to Telling America's Toughest Stories.

Self-assigned to America’s internal war zones — East Los Angeles, Harlem, the post-Katrina Gulf Coast — Joseph Rodriguez spends years working on his projects. He has dodged bullets and accusations from some of his subjects that he is a cop, but mostly he tries to understand what his subjects’ lives are like. Luckily, his own life has provided a starting point. Growing up in Brooklyn, Rodriguez got into drugs, was arrested, and rehabilitated himself, eventually leaving his lucrative graphic-design job for the life of a struggling photographer. He started out as a lab assistant at the International Center of Photography, where he later studied under Fred Ritchin, founder of ICP’s Photojournalism and Documentary Photography Program and a former picture editor for The New York Times Magazine. Through their ongoing friendship, Ritchin has seen the way Rodriguez submerges himself in his stories, and the toll that has taken on the photographer. But as Ritchin says in the following essay, the benefits to the work and the subjects are worth the price.

It is difficult to think of Joseph Rodriguez as a “hero” because he has always insisted that many of the people in his photographs are the true heroes.

I first met Joe in the mid-1980s when he studied with me at the International Center of Photography. Then in his early 30s, he was driving a taxi to support his photography work. Along with his tips, Joe made a nice photo essay from the driver’s point of view, Journey Through My Windows. For more than a year he also worked with a group of ICP students on a project to help those being evicted from their homes due to the gentrification of East Harlem, a neighborhood only two blocks from the ICP’s uptown location at the time. Bruce Davidson, of East 100th Street fame, had recommended my class for the project when the East Harlem Urban Center had come to him asking for help.

| Joseph Rodriguez Gallery****Heroes of Photography Main Article – Gallery The Other Photographers Brent Stirton – Gallery Chris Hondros – Gallery Fazal Sheikh – Gallery Hazel Thompson – Gallery John Dugdale – Gallery Phil Borges – Gallery Stanley Greene – Gallery Timothy Fadek – Gallery Yunghi Kim – Gallery |

After the class ended, Joe kept working in East Harlem on his own. Switching to color, he began photographing there every Sunday, and Howard Chapnick from Black Star photo agency helped him publish his work in National Geographic. It became the cover story. There were drugs, violence, and poverty, but Joe’s story was about the neighborhood, the people, the possibilities — not the spectacle. The May 1990 story, “Growing Up in East Harlem,” was one of several that proved too much for Geographic, its point of view too socially relevant, and the editor Bill Garrett was forced out. But for Joe, East Harlem was not too socially conscious; it was his childhood.

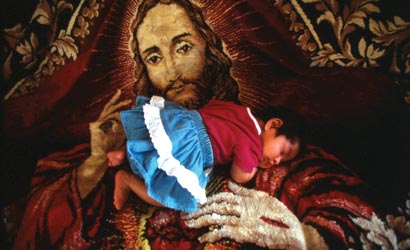

Photography too often confirms preconceptions and distances the reader from more nuanced realities. The people in the frame are often depicted as too foreign, too exotic, or simply too different to be easily understood. The reader is spared, the icons are repeated, and photojournalism begins to resemble the repetitive nature of a religious service, enacting and reenacting the ongoing drama of suffering and redemption while the reader is encouraged to remain in the pews.

But Joe tells his stories — of people we may choose not to see — with such passion and intensity that it becomes difficult to dismiss them as “the other.” Recently he has focused on the still unsolved problems of post-Katrina New Orleans and its evacuees in Texas. As usual, the stories are not easy ones to tell. His “American Gothic” photo shows a skinny 43-year-old woman who was badly beaten and lost her eye. She is flanked by her two young sons, one paralyzed and in a wheelchair, who both bear the scars of gun violence. Struggling under the weight of so many painful stories, Joe frequently felt disoriented, upset, furious, incredulous. “This is America?” he wondered. When we talked on the phone, he sounded as if he was calling from the bottom of a dark well.

Yet these are the kinds of stories Joe is drawn to. Once asked if he would go photograph the ongoing violence in Bosnia, his response was pure Joe: “Bosnia is right here.” At that time he was in East Los Angeles documenting the lives of gang members, which he followed up with a long-term project on California’s juvenile justice system. Like the young people in front of his camera, Joe had known the inside of a prison and the powerful temptation of drugs as a way to deal with despair.

Photographer and teacher Mel Rosenthal has pointed out that so many documentary photographers are “downwardly mobile,” photographing classes of people worse off than where they come from. Joe, one might say, is upwardly mobile — hoping to the bottom of his heart that the people he spends so much time with will somehow, like him, find and follow a more joyous path. And then, give back.

Fred Ritchin, director of PixelPress, is based in New York City.