Heroes of Photography: Fazal Sheikh

Uncovering the Faces of the World's Forgotten.

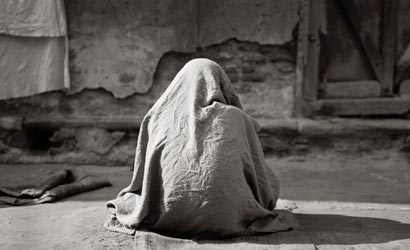

For more than a decade, Fazal Sheikh has been meticulously documenting marginalized communities: refugees in Africa, immigrants crossing the Mexican border, women resigned to second-class status in India. Sheikh, 41, the New York-born child of a Kenyan father and white American mother, considers himself an “artist-activist”; he uses portraiture to personalize large social issues. Among Sheikh’s admirers is Dave Anderson, whose first monograph, Rough Beauty (Dewi Lewis Publishing, 2006), explores the down-and-out town of Vidor, Texas. As Anderson points out here, Sheikh has consciously removed himself from the strictures of “straight” photojournalism to create images of obvious sympathy and respect. Rather than focusing on his subjects’ victimhood, he makes photographs that are, in essence, collaborations.

To this day, only one photograph has ever literally taken my breath away. I first saw “Jamaa Abdullai and her brother Adan” (right) at Cruel and Tender, the Tate Modern’s first major photography exhibition, in 2003. It was an unforgettable moment.

The image was from a series called A Camel for the Son, about Somalian refugees living in Kenyan border camps, and it came from an American photographer with whom I was not familiar: Fazal Sheikh. Alongside works by legendary artists like Walker Evans, William Eggleston, and August Sander, Sheikh’s transcendent photographs more than held their own. His minimalist black-and-white portraits and landscapes, so devoid of pretense but bursting with humanity, seemed to leap off the wall and into my psyche. In an art world that seems to favor icy distance, irony, and garish print sizes, Sheikh’s work is not only heart-stoppingly beautiful but also a resonant antidote to the prevailing winds.

| Fazal Sheikh Gallery****Heroes of Photography Main Article – Gallery The Other Photographers Brent Stirton – Gallery Chris Hondros – Gallery Hazel Thompson – Gallery John Dugdale – Gallery Joseph Rodriguez – Gallery Phil Borges – Gallery Stanley Greene – Gallery Timothy Fadek – Gallery Yunghi Kim – Gallery |

One senses in Sheikh an almost religious tone, a kind of reverence for his subjects. For an artist who does not follow a particular faith, this spiritual quality is striking. “I was never drawn to one faith,” Sheikh says, yet when he describes his work, there is a quasi-religious tone. “I’m most drawn to images that evoke a degree of quiet, calm, or solace,” he says. It seems no accident that Sheikh is a former student of the revered Emmet Gowin, who was his teacher at Princeton University. Gowin, long a practicing Quaker (also my own faith), calls his former student “a spiritual ally.” There is an intriguing similarity of personal manner and worldview between the two: Both project a modest inwardness and virtue that seems almost monklike. Gowin speaks of “thinking compassionately and living compassionately,” which “sensitizes you to deal with other people.” It is clear he believes Sheikh walks this path.

Sheikh focuses on specific injustices that are rarely in the public eye. The radiated warmth in his photographs, the sense of import communicated about the lives of his subjects, and his dedication to bringing attention to those who are deeply marginalized has been an inspiration to me. While his subjects could easily be called victims, Sheikh chooses to photograph them in a manner that accentuates the dignity of their lives, leading the viewer to see that these are people, as he puts it, “not unlike you and me.” He carefully avoids the easy visual vocabulary of victimization: no protruding bellies, no flies on tear-streaked cheeks, no bloody garments or casually placed weapons of war. Instead, he plainly illustrates one honest moment after another with subjects whose lack of pretense and openness demands the respect of the viewer.

Much of Sheikh’s early work was concerned with refugees in West Africa and Northern Pakistan (regions from which his grandfather hailed), while his last several projects have focused on the plight of Indian women: ostracized widows and orphaned girls. I admire the fact that Sheikh begins with a modest goal of simply promoting awareness. “You don’t expect to change the world,” he says. “You try to change views subtly.” His numerous books, from A Sense of Common Ground (1996) through Moksha (2005) and the upcoming Ladli (2007), all frame the issues not only with radiant imagery but also by gently weaving in oral histories and his own elegiac narratives. Many of these projects can be viewed in their entirety at fazalsheikh.org, and his International Human Rights Series project subsidizes and distributes his work to human-rights organizations.

It comes as little surprise, then, that a MacArthur Genius Grant was recently added to Sheikh’s long list of accolades. But a hero? He recoils from the idea. “To think there’s something heroic in spending a month or two someplace where people have to live their entire lives is absurd,” he insists. Typical modesty. But there is something heroic in Sheikh, not only in the quality of his art but in the quality of a life ambitiously dedicated to the betterment of his fellow man. The word “moksha” is defined as “the loss of one’s individual identity and absorption into the universal spirit or the absolute.” Apt words indeed.

Photographer and author Dave Anderson lives in Little Rock, Arkansas.