Spooky animal x-rays are exactly as cool as you’d imagine

They’re spooky-scary.

As part of an animal’s routine check up, the veterinarians at the Oregon Zoo send each “patient” through an x-ray machine. The zoo also recently tweeted out a compilation of their spookiest x-ray pictures as an early Halloween celebration. We talked to a veterinarian at the zoo, Richard Sim, about some of the wild anatomy in each image.

Meller’s Chameleon

“They have a lot of strength in their hands,” says Sim. “Often when gripping a branch, they’ll have two toes on one side and two toes on the other,” as you can see in this image. Chameleons extend their tails for balance, so the fact that this little guy has his curled up into a perfect spiral means he must be pretty relaxed.

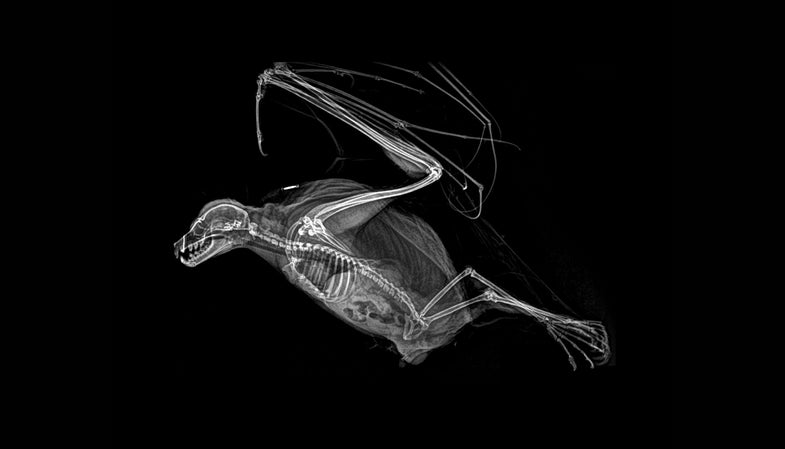

Rodrigues Flying Fox

Taking a look at this bat skeleton you can see the lightweight bones and backwards knees that allow these little mammals to fly. But what’s really crazy are the thin, curved bones at the top of the x-ray. Those are the bat’s fingers. Sim says bats evolved really long fingers to support their wing skin.

Ball Python

A snake’s spinal cord runs from the back of the head to the tip of its tail. Snakes are also the only creatures that have ribs running down the entire length of their bodies, says Sim. In this image you can see the rib bones as the thin lines curving away from the spinal column on each side.

American Beaver

The large bones at the base, where the tail connects with the rest of this beaver’s body, which Sim says allow for “excellent muscle attachment,” allowing the beaver to make powerful motions with its tail. Beavers typically use their tails to communicate—they slap the surface of the water to warn others of coming danger—or to change direction when swimming.

Toco Toucan

A bird’s beak is not one large, bony mass, says Sim. If it were, hornbills and toucans would never be able to get off the ground. Instead, the outside of the beak is a shell of keratin, the same material that makes up human fingernails, and the inside is filled with light, spongy tissue and a boney core. What looks like short veins or cracks in this toucan’s beak are actually pieces of keratin scaffolding holding the beak together.