Landscape photographer Michael Kenna on viewing old work with fresh eyes, and the joys of the analog process

We chatted with monochromatic landscape legend, Michael Kenna, about his most recent photobook, 'Northern England 1983-1986.'

In March 2020, when COVID-19 led to worldwide lockdowns, Michael Kenna had a full calendar of trips and exhibits planned for the months to come. Instead, he found himself stuck at home with nowhere to go. Rather than taking new photos, he went back into his archive to look with fresh eyes at some of his earliest work. The result is Northern England 1983-1986, a book of photos from the area around where Kenna was born and grew up.

What was it like when lockdown hit?

It was ridiculous, as my schedule was absolutely packed in 2020. I had many exhibitions scheduled and book projects ongoing, and I planned to photograph in a number of countries. Then it was a matter of one after another being canceled, postponed, and canceled again.

How did you decide to go back into your archives?

My publisher, Chris Pichler, at Nazraeli Press said we should make a book of something. I couldn’t complete any of the projects I was working on at the time, so it was a matter of looking backward. Fortunately, I have thousands of unprinted negatives to fall back on, and some of these were from Northern England. This work was made before I started going to Japan in 1987. Between 1983 and 1986 I made many photographs on various trips over three or four years. I’d printed some for exhibitions and then just forgot about the rest.

Your photos today are all in a square format, and what stands out here is the fact that these photos are all in a standard 3:2 aspect ratio.

In 1987, I bought my first Hasselblad camera with a waist-level viewfinder. For the 15 previous years, I had been looking through a 35mm viewfinder. Things had become a bit predictable. I composed in certain ways that I knew. I always made the decision, whether it should be horizontal or vertical. I was ready for a change.

How did the Hasselblad change the way you take photos?

After I bought the Hasselblad, everything was suddenly viewed back to front in the ground glass viewfinder. I found it was very difficult to work! But I also found that I began to experiment and do new things. I put the camera on the ground because now I could. I placed the camera just above water to see the reflections from that viewpoint. I propped the camera against the side of a wall. Everything became a little different and my compositions changed to be more graphic.

You are resolutely a film photographer, and always has been. What is it about the process of shooting film that you like so much?

I think the whole analog process exudes calm. For me, it’s a meditational journey. I’m absolutely sure that I could be a photographer without film, without images. I could go through the whole process: travel to places, look for situations and scenery, spend hours exposing, looking at subject matter, and not have a result. It would be frustrating in some ways because I couldn’t make a living, but it is a wonderful process to work as a photographer. I just love what I do from start to finish.

[I love] planning the journeys, making schedules, airline reservations, going to places, finding or trying to find things to photograph—the search, the frustration sometimes, and then suddenly discovering something that is just phenomenally fascinating for perhaps a few seconds or for hours or days. And then there’s the processing and months later first seeing the images, [it’s] almost like opening Christmas packages. “Oh, look at those images! Where did they come from?” Sometimes the photographs I thought would be interesting turn out to be quite ordinary. Equally, sometimes the ones I thought were quite predictable are really interesting! The joy of unknowing! The printing is a whole other story; alchemical and magical with a steep learning curve.

Digital photography, at least for me, takes away some of this indecisiveness, this unknowing of what I have. With film, precisely because it is so unpredictable, I want to search even more. I know myself enough to realize that I have little to no idea when I have an interesting image. That comes later when I see the negatives. As a result, I’m always looking for extra possibilities and options.

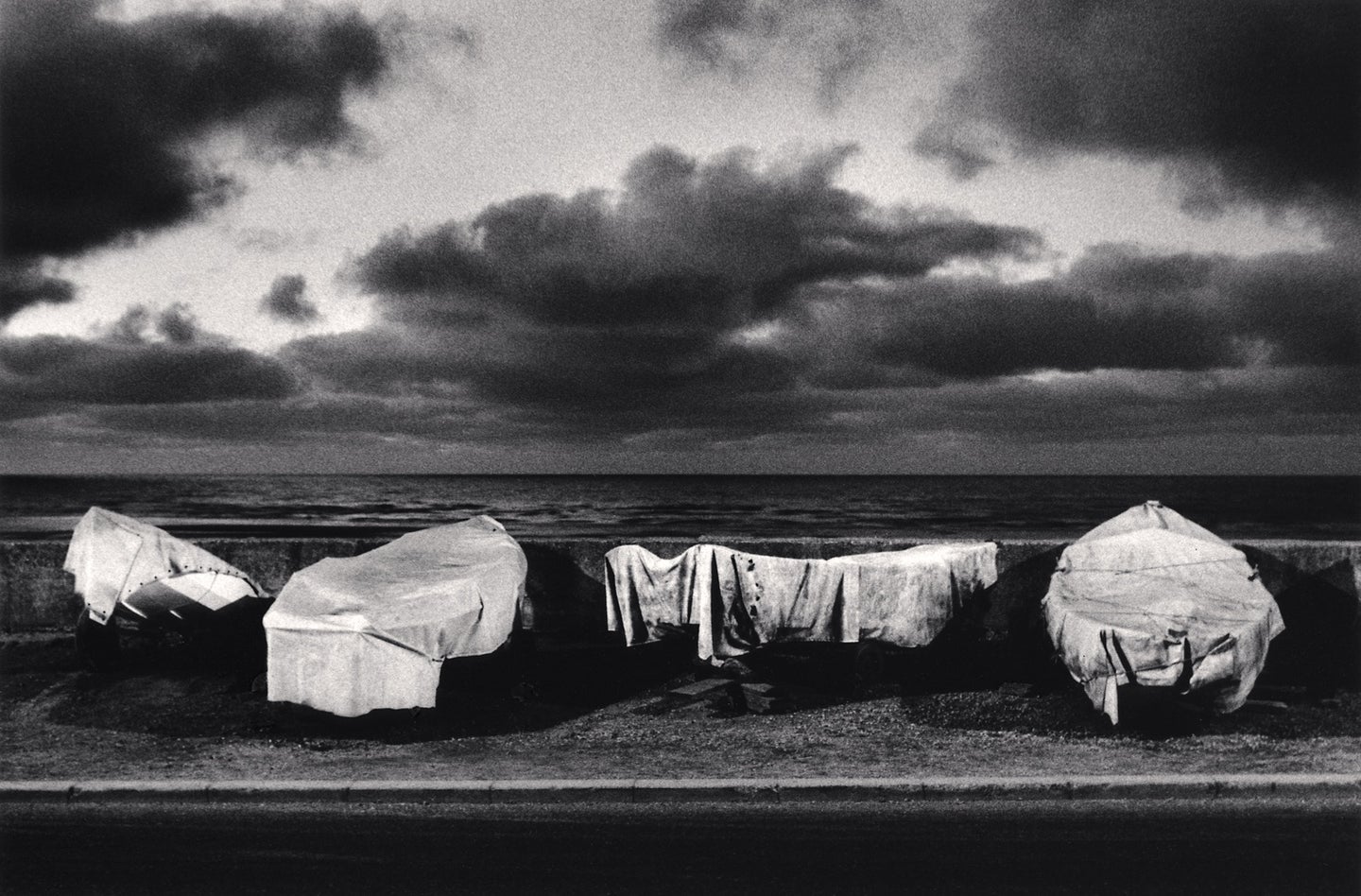

The style of the Northern England photos is similar to your current work: there are no people, and the light and shadows are almost like characters in the scenes. Do you compose these photos as though the are sets on a stage of life?

I sometimes allude to precisely that. For me, my photographs are akin to sets on the stage of life. In this Northern England series, the empty warehouses, for example, had only recently been vacated, many of them were due for demolition, and most are not there anymore. When I photographed [them] at night, along the canals where nobody went anymore, these places were artificially lit as if on a stage.

I sometimes reference my interest in the moments before actors appear, when we can still use our own imagination, and there’s a certain kind of pent-up atmosphere of anticipation. Once the characters are there, I get drawn into their story and listen. I become less aware of the stage as the characters draw me in. After the actors leave the stage, my head is filled with their stories. But before they appear, there is a certain amount of ambiguity, a potential for my own story. I can try to imagine what could happen, what has happened in the past, and what may happen in the future.

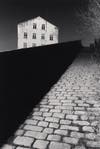

One of my favorite photos in the series is Steep Street, Blackburn, Lancashire, England, 1985. The quirkiness of the titled light pole in front of the buildings means you can’t tell if it’s the pole or the buildings that are tilted.

I still wonder why I didn’t print this image at the time I made it. I love that photograph, but just passed it over when I was choosing my initial selection back in the 80s. When I came across this negative again, I thought, “WOW, that is amazing!” I suppose we look for different things at different stages of our life. I just didn’t see it at the time.

You’ve published dozens of photobooks; how important are they to you?

They’re critically important. I think it’s a duty, a responsibility, a desire and wish for a photographer to propagate their work, to share images, to transmit photographs into the public domain. I’m completely aware that the prints I make are silver gelatin, handmade, hand-retouched, matted, mounted, signed, and numbered. They’re like precious jewels to me, and I absolutely love this process. But how many people are going to see the original prints? Alas, not so many. Books are, therefore, a prime way to show a photographer’s work.

See more of Michael Kenna’s work here.