Photographing War Re-enactors

How to capture full scale battles, hand-to-hand combat and exhausted expressions

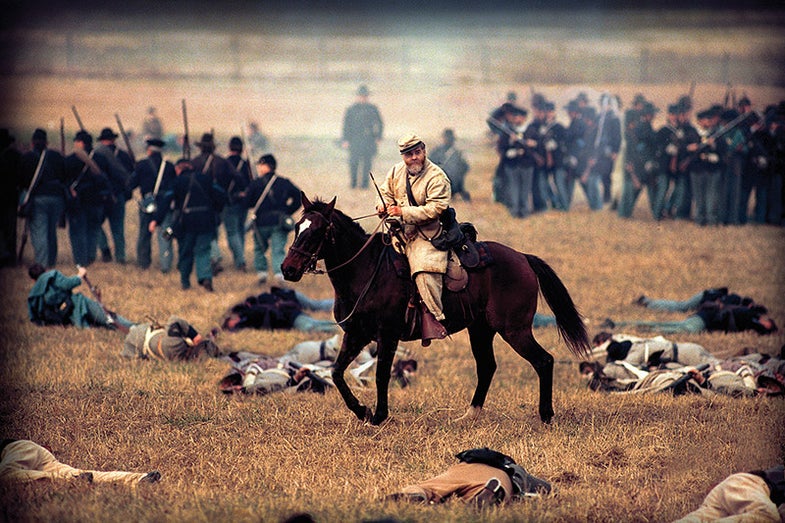

re-enactor

“Everything happens so quickly,” reports Ken Bohrer, a Philadelphia photographer and fan of war-based re-enactments. “Wherever you look there’s something or someone to photograph: Hundreds of soldiers marching in regiments, men dashing back and forth on horses, cannons going off, muskets firing, smoke rising, and soldiers shouting. The best stagings are really like being in battle.”

Sound interesting? You bet. A visit to a battle re-enactment can be an immersive trip backward in time. Popular all over the world, they’re organized around many of history’s most important military engagements, from the Norman invasion of England in 1066 to the Vietnam War. A quick Web search will list the re-enactments nearest you, and the good news is that battle organizers may even welcome you with specially located, roped-off photographer pens.

Battle re-enactments are organized by (often obsessive) history buffs who form intricate societies dedicated to recreating history. These players often impersonate actual military regiments of the past, and they form surprisingly complex societies with their own social hierarchies, vocabularies, and values. Witnessing their intense role playing can be part of your pleasure.

The most common re-enactments in the U.S. depict battles fought in Revolutionary and Civil Wars. And they can feature literal representations of historic battles—sortie for sortie—with encampments where soldiers, women, children, horses, dogs, and chickens form a living representation of military camp life. The encampments give you more than just handsome uniforms and smoking cannons to photograph.

According to Del Hilbert, who owns the Victorian Photography Studio in Gettysburg, PA, and is a portraitist to Civil War re-enactors, these fans divide roughly into three types based on the historical accuracy of their dress and behaviors. If you’re photographing a re-enactment, it helps to know which type you’re dealing with, because each has different expectations of your behavior.

The most accurate re-enactors dress in clothing made from historically true fabrics (down to precise thread counts) that are cut from copies of antique sewing patterns. For posed portraits, says Hilbert, these perfectionists won’t give your DSLR the time of day—they only pose for antique cameras and lenses and for photos produced by antique processes.

Less-serious re-enactors are similar in their passion for accuracy, “but they will sleep in hotels or RVs, not on bare ground, under the stars,” explains Hilbert.

For both these groups, re-enacting is an expensive hobby. Muskets and dress uniforms cost in the thousands of dollars, and regiments spend small fortunes transporting, storing, or renting cannons and horses, among other battlefield accoutrements.

The re-enactors least concerned about historical accuracy, Hilbert says, are called mainstreamers. “They go out and buy way more stuff than they need, and look more like Hollywood creations than actual soldiers,” he explains. Mainstreamers are usually merely tolerated by serious re-enactors, but they just may be your most colorful photo subjects.

Ken Bohrer, a career counselor at Drexel University, explains that there are two main ways to photograph battle re-enactments. Organizers rope off areas for photographers (and their tripods) in places selected for their unobstructed views of battle movements, and with no anachronous, illusion-busting glimpses of modernity to mar the backgrounds. One advantage to using roped-off pens is that you can wear contemporary clothing. The disadvantage is that the backgrounds and lighting for most of your pictures will all have a similar look.

Another way to shoot is to “embed” yourself as a period photographer by actually joining it and becoming a re-enactor yourself. Embedding is a good way to get close to the action, but those old-fashioned photographer duds are scratchy and uncomfortable, especially in the heat. You must conceal your camera, either by holding it down at your side, and very discretely (and quickly) firing. You may also camouflage it inside a box resembling a large-format wooden camera (with darkcloth), mounted on a wooden tripod. There are downsides to this. If you’re embedded in a Union company, the majority of your pictures are going to be of Union soldiers—not so cool if the Rebels have better uniforms.

For photographers, one of the great pleasures of shooting battle re-enactments is that most living historians like being photographed. Del Hilbert is known for his authentic-seeming posed portraits, and he has a number of techniques for getting the right look for Civil War soldiers. “For foot soldiers, the main thing is to capture them looking pretty tired,” he says. “In most of the period portraits, the soldiers have an exhausted, distressed, kind of fearful look. The look of someone who’s been through war.”

Often, you can get these historically accurate expressions late in the day when the re-enactors are tired, hot, and/or bored. Or, as Hilbert does, you can ask for what he calls “a television face.” “It’s the look you have when you’re watching TV. You’re not happy or sad. It’s a blank expression. That’s the Civil War look,” he says. (That look resulted, in part, because the long exposure times in the 1860s required subjects to hold still for 30 seconds and longer. Facial expressions had to be relaxed.)

Also, when you’re posing subjects, don’t make the body language too casual. “People were very conservative back then. You can’t have slouching shoulders or crossed legs. The right look is formal but relaxed,” says Hilbert.

Ken Bohrer notes that the equipment and techniques for capturing the battle action are a lot like those of contemporary sports photography: Fast zooms with large focal-length ranges used on rigs mounted to monopods, or for really long lenses, tripods. Bohrer likes his Nikon 80–400mm f/4.5–5.6G ED VR lens, which he uses on a Nikon D300. The long focal-length range lets him zoom out when the action gets close, or zoom in when it’s distant. A Kenko 1.4X teleconverter gives him even more reach. Also nice: The VR capabilities allow him to handhold the lens and get sharp pictures of all the battlefield action, even as the light is fading.

Re-enactor Jargon

As with many dedicated hobbiest groups, war re-enactors have developed their own colorfully specialized argot.

Campaigner: The most obsessive class of re-enactors. The term nods to their in-depth knowledge of entire military campaigns and their desire to fully immerse themselves in their recreation. On the battlefield, Campaigners are joined by the incrementally less serious Progressives and Mainstreamers.

Embed: To dress a photographer in period costume to resemble Mathew Brady (or his ilk). The embedded photographer may be shooting with either a concealed contemporary or a period camera.

Farb: A derogatory term used to describe a re-enactor whose costume and/or behavior isn’t historically accurate. (The adjective is farby.) The origin of the term isn’t commonly agreed upon, but according to one explanation, it’s an acronym for “From A Reasonable (distance), British.”

**Galvanize: **To flip a re-enactor from his registered side to that of the opponent’s. If too many Union soldiers register for a battle, a number may be “galvanized” to fight as Confederates. Comes from the metallurgical term for applying a zinc coating to iron or steel.

Living Historian: The preferred term for a re-enactor.

Rev War: Shorthand for the American Revolutionary War.

Interested in trying your hand at photographing a war re-enactment? Submit your best shots to our July Photo Challenge: Period-dress Portraits for a chance to be published in an upcoming issue of Popular Photography.

War Re-enactor

War Re-enactor

War Re-enactor

War Re-enactor

War Re-enactor