Tips From a Pro: Gregory Heisler on Portrait Photography

Because making a portrait is different than taking a picture of a person

His new book (which is certainly worth picking up), Gregory Heisler: 50 Portraits: Stories and Techniques from a Photographer’s Photographer, dissects 50 of his photos, including talk about technique and his overall approach to the artform. He took some time to talk with us and share some of his strategies for making portraits truly worthy of your subjects.

I’ve heard that you do a lot of preparation before a shoot. How do you typically get ready?

I never get to a shoot just winging it. I would be very frustrated working that way. I almost always have a very figured out idea. Many times, I’ll actually rough-in the lighting in my studio and do a practice run. So, when we arrive on location, we have a jumping off point. Sometimes we adhere to it very strictly, and sometimes we completely veer away from it, but it gives us a point of departure.

How much research do you do about the person before you shoot them?

I try to talk to the subject before we start shooting if we have time. I may well have read a piece that the photograph will be accompanying if it’s already written. That’s always very helpful because they sort of need to work together.

With that kind of preparation, do you still find that things go wrong?

The truth is that things never cooperate. That’s the name of the game, particularly when you’re shooting on location. In the studio, you’re in control of your entire environment and people are walking into your world. They’re expecting to hand themselves over. When you’re working on location, you’re in their environment. You’re in their world. They walk in feeling like they’re in control of the entire situation, at least initially. It becomes a bit of a negotiation to get them coaxed into your hands.

**What is your personality like on-set? That seems like a crucial thing when you’re trying to form a fast connection. **

Everybody works differently. For me, my father was a salesman, so I’m a real talker. I kind of chat people up. There isn’t a lot of time in my shoots. It’s not like I have time to have lunch with them and talk about their work. It’s really quick.

What can you do with a subject that clearly feels uncomfortable? Are there any techniques you use to help them loosen up?

I try to tell them exactly what to expect. That puts them at ease right away. They come in not knowing how long it’s going to take and they’re worried that it’s going to be uncomfortable. For them, it can be like going to the dentist. If the dentist tells you that you’ll only feel a pinch and how long it’s going to take, you’re put at ease a little bit. I paint a pretty clear picture about what the shoot is going to be like and tell them what I’m aiming for. They usually relax quite a bit.

If someone says to me, “Look, I only have 10 minutes,” I say, “OK, we’ll have you out of here in five.” That also helps to take some of the pressure off and allows them to go into it knowing that the end is in sight, even though we haven’t started yet.

How do you think your process would change if you did actually have time to sit down and have lunch with a person before starting a shoot?

I can’t imagine! I’ve never had the opportunity [laughs]. It would be good, though. It would give me an opportunity to observe the person for a period of time. I could see what their mannerisms were. I could see how they stand, how they sit, how they gesture. I could study them a little while we were chatting. It wouldn’t be so much about the content of the chat providing something to illuminate the photograph, but I could get to know the subject a little bit more.

So, your process starts well before you pick up the camera?

That’s definitely the case. You have to be perceptive. You have to be flexible, and you have to be nimble. You can’t coax something out of someone that doesn’t come out of their own life experience. If you’re photographing someone who is a quiet, serious person, you’re not going to get them to start laughing. If you’re photographing someone who’s pretty gregarious, it might be difficult for them to simmer down. You have to work on the person that’s sitting in front of you. You have to develop your strategy from there.

Can you give us an example of a shoot that went wrong? How did you fix it?

There have been times when it has just been a disaster. I had a shoot with Denzel Washington and he couldn’t have been nicer. We had an idea all figured out. We had a costume designer create–at great expense–a costume that integrated aspects of various characters from his movies. He walked in and said, “I can’t do that.”

I asked him why in the politest way I could and he said, “I never revisit my characters once I wrap the film. I never go back.” There’s nothing you can say to that. That’s certainly a valid position. So, at that point, you start having an aneurism [laughs]. You immediately start panicking.

How did you work around it?

I asked him if he could change into one of the other suits he had there, so I could get 10 minutes to scratch my head and figure out where to go. It gave me time to pace around the studio until I could come up with a second plan. There was a pedestal nearby and I had him stand on it looking like an Oscar in his black suit. It worked.

**Did you try to talk him into it at all to save the idea? **

If all I did was sit there and panic and be bummed out about the fact that he wasn’t going to play my game, nothing good would have come of that. Immediately, you just have to hang a left and start fresh. I’m always game to do that. You have to be nimble.

You have to mourn it very briefly and then move on [laughs]. It’s kind of like the stages of grief accelerated into about 30-seconds. First there’s denial, then disbelief. You have to work your way through them in a hurry and try to end up with some sort of peace and resolution.

Is it tough photographing an actor, or does their training make them good subjects?

Actors are the trickiest. They’re always used to disappearing into a character. The hardest thing for them is to stand there as themselves. They spend their entire lives developing this skill they have to disguise themselves and become someone else. So, when you’re photographing them in character, that’s one thing, but that’s rare. More often than not, I’m photographing them as themselves. That’s a very uncomfortable position for them because there’s no character to disappear into.

What kind of directions do you give on set? Are you throwing out vague suggestions or specific poses?

It varies tremendously. Sometimes it’s non-verbal. I use mirroring, so if I want them to cross their arms, I’ll just fold my arms. There are a lot of non-verbal cues like that. Sometimes I’ll suggest something and then their body language will develop it into something else. For other people, though, you have to say things like “Can you move your left eyebrow up a quarter of an inch?” [laughs]. For them, it’s a mechanical process. You have to be really specific.

The worst thing you can do is to stand in front of someone and just say, “OK, do something. Do whatever you want.” You’d never go to the doctor’s office and expect him to say, “sit however you want.” He’ll tell you where to sit on the table, when to raise your arms and everything else. The firmer and clearer a doctor is with you, the more comfortable you feel. I think the same goes for photography.

Getting over that awkwardness of posing people really can be one of the most challenging things about portrait photography.

If worse comes to worst, one little piece of advice I can give, is to tell your subject that he or she needs to move every time you click the shutter. I don’t care what they do. There might be 25 horrible pictures before you get a good one. Then when you find something you like, just tell them to stop. Let them settle into it. If they don’t move around, you’ll never get the opportunity to see the thing that works.

You’re known for having shot a lot on large-format film where frames are very limited. Has the switch to digital made it easier to keep shooting until you find a pose you like?

I actually shoot less digitally than I did when I was using film. With film, I had to cover exposures and make sure I had extra frames so the lab could test some and things like that. With digital, rather than thinking, “Hey, this is free, I could just shoot forever,” I look at the back of the camera and when I’m done I’m done and I can move onto a new idea. I don’t feel like I have to keep shooting. It allows me to see my progress and lets me know when I’ve got it.

That can be a good thing or a bad thing. For some photographers, I think they give up too quickly. They shoot a picture and think, “OK, I’ve got it,” and they move on. Once you have it, that should allow you to try a new idea.

In your book, you mention that in order to shoot effectively in black and white, you need to start thinking in black and white. Can you expand on that a little?

To me, black and white abstracts reality. It makes it one step removed. Black and white makes it more about the feeling of something than the fact of the thing–what it felt like rather than what it looked like. I immediately get into that mindset.

When you’re shooting digitally, I’ll set my camera to JPEG + raw and set the camera to monochrome, so what I’m seeing on the back fo the camera is a black and white image. I’m recording a black-and-white JPEG as well as a raw file that’s in color. The black and white JPEG is like a little reference for me later, like when I’m in Lightroom. It helps me remember what it is I was going for and then I can use that to work with the raw file. It’s a great thing to be able to do.

Digital is this amazing platform for black and white. It leaves you so much room for interpretation. I always made my own black and white prince in the dark room. I never had my assistants do it. For me, I can be a much better printer digitally than I could in the darkroom. I can make finer adjustments and reverse them. I can reinterpret a picture 50 different ways if I want to. It’s very exciting.

Do you ever find all those options to be overwhelming?

It’s about having a clear sense of what you want the outcome to be. It’s like having a giant toolbox. You’re only going to use the tool that you need. It’s not like “wow, I have all these tools! Maybe I’ll just use them all!” To build something, you use a hammer when you need a hammer and a screwdriver when you need a screwderiver. You don’t use a chainsaw just because you have one.

Sometimes, though, people do wield the proverbial photographic chainsaw

That can be true. I tend to think of it as a digital darkroom, so I don’t tend to do all kinds of crazy moves.

There are fantastic people who work in post, but I prefer to do it myself, not because I’m better than they are, but because I’ll make decisions I would never ask them to make. I may never think of them. I’ll be there working with a picture and I’ll think, “Hmm, I wonder what would happen if I did this or that.” I explore all that myself and that’s very exciting.

How much film are you shooting now?

Zero. I literally stopped around 2005 or 2006. I made a conscious decision to put all my big cameras in the closet. I put a clothespin on my nose and I dove into the digital world. I thought, “I have to give this one year.” I thought digital would be like a passing spell of bad weather that would go away. But, I decided to take one year to really try and embrace it. I really haven’t looked back.

Do you miss it at all?

I miss my old cameras a lot and I’m sure I will go back to them. I miss the process of working with the big cameras, but in terms of the actual outcomes of the photographs, I’m very happy with the results I get digitally.

I didn’t expect to be at the bottom of a really steep learning curve. But, once I got a handle on it, I loved it.

Do you shoot digital medium format digital or standard DSLRs?

I shoot both. I do the bulk of my shooting with a Canon 5D Mark III. I have an older Hasselblad H1 with a Leaf back and I use that for some of the portrait work I do. With the Canon, though, the quality is so good and it’s so versatile. Also, one of the reasons I switched to Canon years ago was that they have all these tilt-shift lenses, which give me a lot of the control I had with my large format cameras.

How often do you use the tilt-shift lenses?

When I’m out shooting with my Canons, I’ll just bring the tilt-shift lenses. I’ll bring the 24mm, the 45mm, and the 90mm tilt-shift and that’s it. I don’t bring fast lenses or zoom lenses. And I work with it on a tripod using a cable release. It’s like I’m using a large format camera when I’m doing portrait stuff. I don’t have the camera smushed up to my eye. I’m standing next to the camera talking to the person.

It seems like fewer and fewer portrait shooters are using tripods. What is it about that setup you like so much?

There are a bunch of reasons. I like standing next to the camera so I can talk to the person, but there’s also the matter of sharpness and preventing camera shake. The camera can shoot at higher ISOs, but I pretty much never shoot at anything above the native ISO. It’s about picture quality.

It’s also about composition. The way I shoot my portraits a lot is by figuring out my frame, then putting the subject in there. A lot of what people consider portraits to me aren’t portraits. It’s not like shooting a canvas shot with a 180mm lens. That’s not a portrait. It’s a picture of a person, but it’s not a portrait.

A portrait to me is much more figured out and collaborative. I’m actually figuring out my frame very carefully on the tripod, and then the subject comes in and they become a part of this frame that already exists.

There’s a terrific photographer, Sam Abell, who shoots for National Geographic a lot and his mantra is “compose and wait.” He actually finds his frame and waits for things to happen within that. I try to build on that. My mantra is sort of “compose and make shit happen.” [Laughs]

If you remove a subject from the portrait–if you put your thumb over them–would there still be an interesting picture there? And with my pictures, it’s not always, but to a great extent, they would still be interesting to look at. That’s a big reason for the tripod.

Once you have shot all the photos, what’s your process for picking out the best image?

I go through several rounds. First, I go through and knock out the bad ones. Then, I narrow it down to the better ones. Usually the best one pops out pretty fast. You can usually tell right away. There are peak moments and expressions that I’ll remember from when I was shooting. I’ll see it pop up on the computer and I’ll think, “Yup, that’s the one.”

How do you think the barrage of photos we see on things like Instagram has affected photography on the whole?

I think people are more into taking pictures than ever before, which is a good thing. I think it has been a great equalizer. If a guy goes out and buys a violin, he’s just a guy with a violin. A guy buys a camera and he’s a photographer. Now, that’s even more so. It’s one thing to buy a camera, but everybody has a phone. So in a way, everybody is a photographer now.

It has empowered a lot of people to make images and share them, which I think is exciting. There’s lots of crap out there, but I think people are more visually literate than they ever have been. The more people you have interested in images and making photos, the more sensitive the public is and I think that’s great.

How does that affect the role of a professional photographer?

I think it’s great for professionals because it pushes us to do more and more interesting things. The ante has been raised and I think that’s a good thing.

Is there anyone out there you’d love to photograph but haven’t been able to yet?

Right now it would be the president. I haven’t had the chance to photograph Obama and I’d like to do that.

Do you have an idea already thought up for the shoot?

Of course! I probably have 17 ideas [laughs]. Maybe more!

Bruce Springsteen

Muhammad Ali

Liam Neeson

Hugh Grant

Joyce Carol Oates

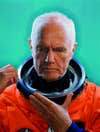

Neil Armstrong