Shooting in Hell

Voyage through the jungle and deep into the darkest heart of the earth. Then come back with great photos.

“Flash floods, assassin bugs, poisonous gasses,” Bruce Hagan, head of Global Medical Rescue Services and an expert on wilderness survival, ticked off the hazards of caving as he downed another rum-and-Coke. It was just past the witching hour and we were elbow-to-elbow at the open-air bar in Ian Anderson’s Caves Branch Jungle Lodge, a rustic retreat deep in the misty hills of western Belize. “And, of course, there’s the rabid bats, lung diseases, and venomous snakes.”

Hagan, a bear of a guy with a handlebar mustache and tattooed biceps, had come to this New Jersey-sized nation wedged between Mexico and Guatemala, not for Belize’s most famous natural attraction — the cerulean lagoons and rainbow-colored corals of its own Great Barrier Reef — but for the country’s lesser known underworld. Caves.

The mountains of Belize are honeycombed with thousands of caves, a photographer’s dreamland of polished stalactites and subterranean rivers. But they’re also the stuff of nightmares. To the ancient Maya, caves were portals to the spirit world of demons and gods, Xibalba, “the place of fear.” And after hearing Hagan’s grocery list of caving perils, it was easy to understand why.

I nodded at the bartender for another Cuba Libre and thought about the perils I was about to face. I’d come to photograph Xibalba. For most of my career I called myself a “natural-light” photographer, a professional way of saying, “strobe photography befuddles me.” How on earth, I wondered, as a midnight moon rose above the jungle pressing in on the lodge, was I going to photograph a pitch-black hell?

JUNGLE EXTREMES

“You don’t find an exposure,” National Geographic legend Bill Allard once corrected me when I admitted my trouble with fill-flash photography. “You build one. You create it like a chef.”

Allard’s recipe for fill-flash? He starts by metering off “found light” — ambient sources, like the sun or a neon sign. “Underexpose the entire scene by a stop or two, and crank your strobe low, sometimes as low as it will go. Then mix the ingredients.” By building on light sources, you can eke out color and sharpen edges. This is especially important in high-contrast scenes where digital cameras notoriously clip the shadows and highlights.

That was the situation I found while hiking to the caves. I wanted some shots of Glen and Brian — two friends I’d conned into joining me as photo assistants and reluctant models — here in the jungle.

Hundreds of feet above our heads, the dense canopy of ceiba trees and strangler figs blocked out 98 percent of the blazing midday sun, casting us in green shade. The 2 percent of solar power piercing the screen glowed like flames on the shiny leaves. When I exposed for skin tones, the highlights blew out. When I exposed for the sunspots, Brian and Glen became a pair of faceless Grim Reapers. It was a “lightmare.”

The solution? I popped an SB-800 Speedlight on my Nikon D200, cocked it up at a 45-degree angle, extended the bounce card, and began stirring Allard’s recipe.

To keep the jungle a cool, forest green, I flipped my white balance to Sunny. To add a kiss of sunshine to the skin tones, I taped an amber filter on the strobe. In the end, I’d concocted a recipe that balanced the contrasting light and illuminated the emerald jungle.

LIGHTING IN 3-D

On-camera fill-flash, however, wouldn’t get me much further than the mouth of a cave. And when Abel, our guide, disappeared into a gap no bigger than my shoulders beneath a mossy boulder, I left the one-dimensional world of ambient light behind.

The most surreal — and claustrophobic — aspect of caving is the sensation of moving through a medium, not over one, as on a forest trail. A few shots of Brian slithering into the tunnel proved that a single on-camera strobe wouldn’t capture the three-dimensional experience. I needed more tools.

The first tool was my sync cord. By getting the strobe away from the lens, I was able to create some depth with angled shadows on Brian. Then Glen placed a second SB-800 strobe on a mini tripod behind a rock to illuminate the stone walls from a different angle. The two strobes together carved out contours.

In a minivan-sized chamber, we’d made a photo studio. And it only took an hour. An hour of Brian frozen on his elbows and knees on sharp stones. An hour of Glen tucked into a ball behind me, repeatedly dialing the strobe power up and down as I shook my head, “Too hot, drop it back to a quarter power.”

Absorbed in the moment, I stared at one of the strobes to adjust the diffuser and my world suddenly exploded.

“Sorry,” Brian’s disembodied voice came through the white blankness. As pinpricks of light sparked in my brain, I heard snickering. Time to move on.

“She was probably brought here as an offering to Ixchel, the moon goddess,” Dr. Jaime Awe said as we packed our gear into waterproof Lowepro camera daypacks and adjusted our helmets at the entrance to Actun Tunichil Muknal. A limpid river streamed through a mouth draped in vines; outside, it looked like a set from a Stephen Spielberg film. But the inside was all Stephen King.

Discovered in 1989 and opened to the public in 1998, it is the most famous cave in Belize. Awe, director of the Institute of Archaeology, which manages the country’s archaeological treasures, led us into the darkest heart of Xibalba, into a cave where the Maya met their demons. One who never returned was a nameless 20-year-old woman known only as “the Crystal Maiden.”

We worked our way past a rock-fall maze, squeezed through narrow cracks, forded oil-black pools. Four hundred feet beneath the rainforest, a half-mile inside Xibalba, we emerged into a chamber as big as a Broadway theater. Our headlamps illuminated a magic world of candlewax stalactites and travertine dams. The floor was littered with hundreds of ceramic jars and pots; Awe said more than 1,400 artifacts have been cataloged here.

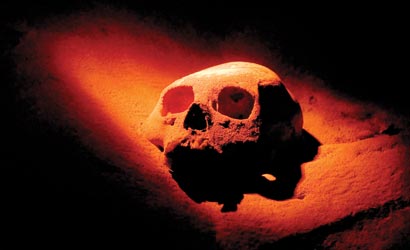

There were also skulls and long-bones. “At least 14 people were sacrificed here,” Awe said as we tiptoed among the relics.

Broad shotgun blasts of light from multiple strobes wouldn’t do the delicate artifacts justice. We needed something more precise. Next to a collection of a pots, I set up the tripod and employed a technique custom-made for the Polaroid character of digital photography — light painting.

The concept is simple, and the results colorful and artistic. With your camera on a tripod set for a long exposure, you use a flashlight as a paintbrush, stroking different parts of your subject. Vary the time the focused light spills on a particular surface and you control its intensity. Move farther away from the camera-to-subject line of shooting, and you create different moods.

With my self-timer set for 15 seconds and the D200 in mirror-up mode to reduce vibration, I had time to press the electronic cable release, walk over to the pots, click off my headlamp and paint. For the next 2 hours I experimented with exposures ranging from 30 seconds to 4 minutes.

Finally, it was time for the Crystal Maiden. We found her in a catacomb high above the main chamber, where she was most likely sacrificed more than 1,000 years ago. Her skull was tilted back, jaws open in an eternal scream, her bones so crusted in calcium carbonate that they sparkled like broken glass.

I spent more than 3 hours in her tomb, taking light painting a step further by creating a palette of painted images from the same position. One of her skeleton, a couple background shots of cave formations. I even popped a strobe on Awe as he crouched beside her. Then I combined them all into a single exposures using the D200’s in-camera multiple-image software. No need for Adobe Photoshop.

DEEPEST DARKNESS

Humidity soon built in the sepulcher from the heat of our wet bodies, and my lenses fogged. I asked to shoot solo for the last hour to clear the air. It was a mistake.

I heard a woman’s voice whispering in the dark. Another caver? The gurgling river in the blackness below? Something else? Turning around to a noise, I thought I caught the flash of a bare leg disappearing behind a stalactite. Glen playing a prank? Ghosts hadn’t been on Hagan’s list of caving joys. The maiden was done modeling and I was done shooting. I hastily packed up the camera and retreated backwards out of the open grave.

At the lodge that night, Bruce nodded when I told him how it felt to be up there alone with the maiden. “Sacrificial caves are a world apart from other caves,” he said. “They’re dark. And I’m not just talking about cave-dark,” he said, sliding a drink in front of me. “I’m talking about light-sucking and life-sucking dark.”

Life-sucking dark. I wondered if Allard had a flash recipe for that.

BELIZE

Want to explore the country’s caves? Here are two good contacts:

• Belize Tourism Board: 800-624-0686; travelbelize.org.

• Ian Anderson’s Caves Branch Adventure Company & Jungle Lodge, cavesbranch.com. Set on the 58,000-acre Caves Branch Estate, this wilderness lodge an hour west of Belize City offers expeditions to sacrificial caves (including Actun Tunichil Muknal-Cave of the Crystal Maiden), jungle survival courses, river cave tubing, jungle treks, and overnight camping expeditions. This outfitter also can arrange caving day-trips for those not staying on the property.