Adventures in The Forbidden Zone

How stealthy photographers get great shots where others fear to tread.

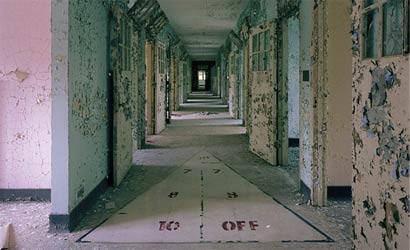

Howl, Allen Ginsberg’s ode to alienation, invokes “the visible mad man doom of the wards of the madtowns of the East.” A few of those madtowns — vast insane asylums in campus settings — are still standing, abandoned and rotting into exquisite ruin. And, in the same way that photographs of the empty wrecks speak more eloquently than if the buildings were new, Howl’s description of one of them is even more accurate now than it was when Ginsberg’s mother died there in 1956: “Greystone’s foetid halls, bickering with the echoes of the soul, rocking and rolling in the midnite…”

Recent pictures of Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital capture that poetic vision. Founded in 1876 as the New Jersey State Lunatic asylum, north of Morristown, this is where folk music pioneer Woody Guthrie spent five years, 1956 to 1961, as he was ravaged by Huntington’s disease. He was visited on Ward 40 by an awestruck Bob Dylan, who later wrote up the encounter in “Song For Woody.” Wardy Forty, as Guthrie called it, was a synapse in modern musical history that has been moldering away and off-limits since the mid-1970s.

That hidden dilapidation is exactly what interested photographer Phillip Buehler. His photographs of the disintegrating landmark will be published in a book, Wardy Forty: Woody Guthrie at Greystone Park (University of Illinois Press).

Guthrie, bickering with the echoes of his own soul, was committed to Greystone because of a misdiagnosis. He was photographed the day he arrived in 1956 and the day he left, in 1961. In 2002, those two pictures were still in the basement files, along with about 50,000 other negatives, when Buehler and a friend, having approached stealthily through the woods on bicycles, evaded security (there’s a police station across the street) and entered the imposing, Neo-Gothic, gray granite edifice.

| Breaking & Entering”Rana, get down!” Ryan hisses. Rana X (her nickname and studio name), a 26-year-old urbex photographer with a few hundred trips to about 30 asylums under her belt — not counting prisons, industrial sites, and other derelict places — drops to her feet. A construction worker on the grounds of the abandoned farm colony above is wandering near the fence less than a dozen yards away.After huddling on the ground for about 15 minutes, we scramble up the steep surface to the colony, slipping on dead leaves and hanging to clumps of brambles for balance. At the top, we boost our gear through a gap in a rusty chain-link fence and shimmy in.Our last obstacle is the guarded road that leads to our destination: an asylum on the grounds of the colony that’s been abandoned since it closed in 1975. This we do in sprints. Finally, we’re at one of the ward buildings, hooded and eerie behind a wall of towering pines. Rana pulls open the door. We’re in.In all, a tame break-in. Rana and Ryan are both used to scaling barbed-wire fences and dashing through wooded complexes at a run from state cops. In one, a security guard would stalk them through the underground tunnels, leaving “party poppers” (small novelty fireworks) at the entrances, which the unwitting explorers set off as they climbed down into darkness. Last week, Rana tells me, she visited an abandoned hospital at a state prison. “If they’d seen us and thought we were escapees,” she realizes, “they could have shot at us.”Now, to avoid a sensor, we leave our flashlights off as we climb through the unlit stairwell, slipping on mounds of dust and flaked-off drywall on the stairs. Then we’re at the top floor stairwell, stepping into the fifth-floor ward. Vines creep through the broken windows lining the back walls, overlooking a rolling green expanse of woods studded with red brick Mission-style ward buildings. The floor is littered with artifacts — an abandoned wheelchair, a faded blue stretcher, bleached-out catalogs from the ’70s. On the floors below, we’ll find a straitjacket, electroshock equipment, a broken piano lit by flickering fluorescent lights. Massive holes in the walls create a series of views into examination rooms beyond. In short, photo ops abound.Danger averted, Rana and Ryan put their flashlights away and drop their bags. Ryan sets up his tripod, and Rana fits a lens on her Canon EOS Digital Rebel XT. After all, it’s partly about the thrill. But mostly it’s about the pictures. -Lori Fredrickson |

Buehler had his Mamiya 7 with a 43mm lens and Provia film — check. Cell phone on vibrate — check. First aid kit — check. Rope in case someone falls through a floor — check.

Buehler has shot pictures in forbidden places all over the world, including an airplane graveyard near Tucson, AZ, a now-demolished Alcoa aluminum plant near Edgewater, NJ, and rotting U-boat bunkers built by slave labor in the 1940s near Bremen, Germany. (You can see more of his work at www.modern-ruins.com.) He’s part of a growing movement in which photographers are becoming curators of a receding reality. There’s no denying the romance of wreck and ruin — and photography is a passageway and an excuse to wallow in it.

Abandoned chemical plants, timeworn miniature-golf courses, silent steel mills. The dilapidated city of Gary, IN. Nevada’s 1,375-square-mile nuclear testing grounds. Parched water parks, secret ghost towns, the decommissioned missile bunkers ringing most major cities. Pretty much everything in the built or altered environment is being photographed for posterity, with or without official permission.

Most of us have done this inadvertently. Whatever it was that drew me to the paddle wheeler graveyard up in the Yukon, or the jungle-choked secret army base now manned by monkeys on an island in the middle of the Panama Canal, is the same thing that pulls us all toward a place we’re not supposed to be, a zone with no rules, off the cultural grid. People are competing in a form of one-downmanship, braving asbestos, PCBs, poison gas, radioactivity, killer mold, venomous spiders, rats, meth freaks — and, of course, cops and trespassing citations — to locate and capture in pictures the played-out dreams and flyblown empires retrogressing in civilization’s rearview mirror.

Digital technology is driving the craze. You can guile your way into an old rackabones building in the morning, shoot 40 images, upload them onto a website that evening, and read global commentary on them before midnight. Buehler calls himself a photographic historian, but others call themselves industrial archaeologists, urban explorers (“urbexers”), drainers, and cataphiles — those who like to slither underground into Parisian catacombs and L.A. storm drains. Almost all of them carry cameras.

In the abandoned darkroom downstairs at Greystone, Buehler shot the overflowing photo-file cabinets of long-gone patients, but didn’t touch a thing. “Once you have a photograph of it, you’ve rescued it in some way,” he explains.

He found out later that the Woody Guthrie Foundation and Archives were in Manhattan, and that led to the troubadour’s medical record numbers. Then Buehler snuck back into Greystone, used the numbers to locate Woody’s mugshots in the file drawers, and liberated them from oblivion. The 5×7-inch negatives are now part of the Guthrie archives.

Rescuing such sunken treasure is almost unheard of, though there are plenty of patient records, electroshock machines, and other artifacts still hidden in the festering remains of asylums. (The patient negatives and medical records at Greystone were hastily cleaned out by authorities after Buehler’s story appeared in the magazine Weird New Jersey.)

Still, East Coast urbexers are spoiled. The Kirkbride insane asylums, built in the late-1800s to the specifications of mental health pioneer Thomas Story Kirkbride, really were madtowns, with their own post offices, carpentry shops, and fire departments. The two dozen derelicts still standing, originally designed in grand styles by leading American architects, are spread all over the Northeast. Photographs inside these deteriorating structures, usually shot with available light, often evoke Howl’s “visible mad man doom,” and reach the level of art.

Ian Ference, a 25-year-old full-time urban explorer and photographer in New Jersey who hangs with a small cell of about 15 likeminded, even high-minded, fellow ruin-rooters, has gone as far as to use grappling hooks and knotted ropes to climb into second-floor windows. Sometimes he and his companions “predawn” a building so they can doze inside until the sun comes up. They rarely use flash, which tends to blast out the creepy texture of peeling paint and the end-of-the-world half-light oozing through tattered curtains.

Ference has made 30-minute exposures using his 30-year-old Minolta XD 11, loaded with Fujicolor Pro 160S. “My thing is institutional tubercular sanatoriums, psychiatric asylums, and prisons,” he says. “They have the most history, the most pathos. They’re part of our collective heritage that’s being lost.”

But I’m a West Coaster, and although there’s some decent devolution underway out here — haunted old theaters in Hollywood, abandoned shipyards in San Francisco Bay — this is no Rust Belt. Our ruins are less dramatic than a chemical plant or a desiccated amusement park.

Still, like every other American city, San Diego, where I live, has storm drains, all of them off-limits, most of them regularly explored by a small group of urban adventurers. So one Saturday morning I met Dan C. and Rob R. for an excursion into a 12-foot-diameter drain that extends from Balboa Park to the bay.

First aid kit — check. Headlamps — check. Nylon socks and running shoes so we can get our feet wet but dry out quickly — check. Deflated rubber rafts — check. Short-handled paddles — check. Raft pump — check. Heavy-duty lights for photography — check. Cajones — uh, well…

We skulked down behind a parking lot and crossed a busy street, three guys with curious loads rolled up and tied onto their daypacks. We passed through an unlocked gate, butt-slid down into a concrete culvert, and trudged about a quarter-mile until the channel disappeared into a 12-foot-wide steel gullet, which swallowed us into perfect darkness.

Once past the imbecilic graffiti tags near the entrance, we crept along the dry pipe under a major highway. Some decent graffiti art appeared in our headlamp beams, reminding me of the elaborate murals under Los Angeles a drainer had told me about. Cave art in the pitch blackness beneath our cities was a comforting thought. It distracted me from wondering if antiterror agents in black Ninja outfits were lurking somewhere, like the full-time catacomb patrol unit of the Paris police department.

| The Compleat Explorer What to Carry • Backpack • Water • Headlamp • Cell phone (on vibrate) • ID • Lightweight tripod • First aid kit • Duct tape • Flashlight with extra batteries • Gloves, latex and leather • Tabby boots (for climbing chain link) • P-100 breathing mask (for asbestos protection) • Hazmat suit (for Superfund sites) • Geiger counter (for nuclear test sites) • GPS unit with topo map programs • Oxygen analyzer (for tunnels, shafts, and mines) • Pepper spray (for bums and meth freaks) • Hand wipes (use before fiddling with photo gear) • Inflatable raft, with pump and paddles (for storm drains) • Nylon socks (they don’t hold water) What Not to Carry • Spray paint • Lock-picking tools • Crowbars • Bolt cutters • Universal elevator keys • Weapons (make your own call on Leathermen or SAKs) |

We’d already passed beneath the downtown and had seen many small feeder drains leading up to grates in the gutters above us. Occasionally we encountered high-vaulted chambers with ladder rungs leading up to manhole covers, faint shafts of light shooting down through air holes in the iron discs. “‘When it rains, stay out of the drains’ is one of our mottos,” Dan explained helpfully. More darkness slipped behind us.

More than a mile in, we came to a split in the round pipe where it branched into two square concrete channels with a lower ceiling. I shined my dive light into the void, and there was a River Styx clogged with floating plastic jugs, cigarette butts, and a waterlogged mattress. It was time to grab the pump and become blackwater rafters. Our voices sent eerie echoes down the pipe in front of and behind us. Mine was the highest. I’d had enough. No subterranean rafting today. We shot a group photo and turned around.

In a Dry Country

4 WD drive vehicle — check. Desert camping gear — check. GPS unit with topo map programs — check. Canon EOS 30D with tripod — check. Six-gun — check.

Lewis Shorb has to be able to shoot more than pictures when he hikes into the high deserts of California and Nevada, looking for ghost towns. “You’ve got to assume everybody you encounter is armed,” he explains. “And we’re running across more meth labs set up in old mine shafts.”

Shorb, 48, is a serious photographer devoted to chronicling humanity’s footprints in godforsaken places (see his work at www.ghosttownexplorers.org). He’s not interested in touristy ghost town parks like Bodie or Calico. “Anywhere near a road, there’s not much left,” he says. “Old cabins become firewood. Treasure hunters are how ghost towns disappear.”

Shorb and his small clan of historians and desert rats pore over out-of-print government mining reports for clues to the locations of especially productive mines, which would have had sizeable settlements nearby. When he bushwhacks into a remote area and hits pay dirt, “sometimes it’s hard to believe how many people lived out there in the middle of nowhere. You’ll see the remains of what were beautiful brick structures, all gone.”

Some of these tough old towns are still on working claims, most guarded by a caretaker. “It’s usually a crusty guy with a gun, but that’s part of the fun, those characters,” says Shorb. “At the Blue Jasmine Mine in the Western Sierra, a couple of hours from Nevada City, there’s a caretaker who hasn’t left the property in three years. He looks like the Hobbit, bald on top with long gray hair around the sides. Lives on the Yuba River, generates his own electricity with a little water wheel connected to a Ford alternator. He has a satellite hookup to the internet and sells gold nuggets on eBay.”

Shorb says if you’re nice, and interested in history, and maybe bring along an extra case of beer, most caretakers will allow you in to see the old mining equipment or wander the bleached clapboard buildings. But it isn’t for the ill-equipped. When I told him I was going down in the storm drains, he asked, “You taking an O2 analyzer?” He cautions that exploring mine shafts and other tunnels is inherently dangerous, and that two men died in Nevada a couple of years ago from poison gas just 75 feet into a mine shaft. “You want a breathing mine, one you can feel cool air blasting from. That means the miners cut a ventilation shaft.”

The desert mummifies everything into jerky, so Shorb’s pictures have more of a frozen-in-time feel than images of the asylums or other structures more actively rotting back east. But they offer the same message: Only in retrospect does the true nature of existence become clear, when the fragility of all living things, animate and inanimate, is revealed.

Steal This View

This hit me at an inopportune moment above hazy San Francisco Bay, as I was gripping welded-steel rungs and climbing up through a man-cage toward the working end of a towering dockside crane.

The rust-pocked behemoth was left to the gulls and the corroding sea along the quay of Mare Island Naval Shipyard when the base closed in 1996. Jef Poskanzer, a Berkeley-based urban explorer and “industrial archaeologist” who was climbing up behind me, had wanted to document the base for his website on the Bay Area, www.jef.poskanzer.org.

We’d already inspected the base hospital, with its 1919 sundial still keeping time and a dried-up therapy garden with sweet purple grapes hanging heavy from a spindly arbor. But up on the crane, stepping lightly on rusty steel decking, the tannic aftertaste of the grapes was replaced by the metallic tang of fear.

“At least it isn’t windy,” Poskanzer chuckled as he brushed past me in the trashed winch room, climbed some more rungs into the glass-enclosed operator’s booth, and started aiming his Panasonic Lumix DMC-FZ10 with a 35-420mm (equivalent) Leica DC Vario-Elmarit lens.

Below us spread an end-of-the-world diorama. Three immense dry docks, piles of rusting steel ship innards, a dead forest of reeking pier pilings, gutted cranes lined up like exoskeletal dinosaurs. The hulking black sail and diving planes of a nuclear submarine was silhouetted in the luminous mist. We spied the rip in a chain-link fence we’d need to crawl through to reach all these goodies, and descended into the heap.

In person, the view seemed historical, a peek at time’s back lot, but in the pictures uploaded later that day, the scene was transformed by the camera into a vision of the postindustrial future.

If you enter a structure that’s abandoned, not fenced, and not posted with “No Trespassing” signs, you generally can’t be issued a trespassing citation. But, “all the best places are the hardest to get into,” says Ian Ference, an aficionado of fenced-off asylums.

And trespassing is not to be taken lightly. Get caught with the wrong tools in the wrong place by the wrong guy, and you can end up doing real time. What you might think is a misdemeanor might actually be felony breaking and entering. “The possibility of getting caught is part of the attraction,” says Jeremy Harris, a West Coast-based explorer, “but it’s also an annoyance.”

Or worse. Consider the explorer chased down last fall by men in tan outfits on the grounds of a Church of Scientology bunker complex near San Bernardino, CA. This is an “active” site — at least partly occupied. They called the police, and “Joe Earthworm” (he requested anonymity) was arrested for trespassing. “I intend to fight it — they’re crazy. The property was not clearly marked,” he says.

In fact, a lack of signage won’t always shield you. In some states, like Colorado, you can be convicted of trespassing even if there are no warnings. In most states, it won’t help if you’re caught with weapons or tools that could pick locks or jimmy deadbolts. That boosts the charge to a fourth-degree felony in New Jersey, with jail time of up to 18 months.

Your best protection? A camera. “My camera is a get-out-of-jail-free card,” says Phillip Buehler, who rowed a boat out to dilapidated Ellis Island when he was 17 to take pictures — illegal, of course. Now he’s 49, and some of those photos are in Ellis Island’s archives, as is his account of exploring the human gateway 30 years ago.

When Buehler is confronted by security guards or police, he becomes “all respect, first and foremost.” He uses his camera to show he’s no vandal, and tells them he’s trying to preserve these places before they disappear. If that doesn’t work, he suggests groveling.

Security cameras, motion sensors, proximity alarms — all in a day’s shooting for hardcore photo explorers. Then there are the tommy guns. At Nevada’s Nuclear Test Site, north of Las Vegas, “There are guys driving around with machine guns,” warns Peter Kuran, a filmmaker who has shot as well as sleuthed from government archives hundreds of photos related to nuclear-bomb tests. “You wouldn’t want to trespass out there.”

Other ways determined explorers get the shot without getting into trouble:

• After approaching a site on bicycles, they pull the bikes inside behind them.

• If they remove screws to free a board to get inside, they pull the board up behind them and screw it back in when they leave.

• In the desert or backcountry, they always chat up the caretaker about the history of the place, offer refreshment, and politely ask for permission to enter private property.

• In case they get caught, they make sure they’ve brought along proper identification. “I’d rather carry ID and get a citation than not carry it and get arrested,” says California cataphile Dan C.

• And for that golden moment between the security guards’ call and the cops’ arrival? They wear good running shoes.

Additional Resources

Books

Access All Areas: A User’s Guide to the Art of Urban Exploration, by Ninjalicious; Infilpress (2005)

Dangerous Places: Health, Safety, and Archeology, edited by David A. Poirier and Kenneth L. Feder; Bergin & Garvey Paperback (2001)

Dead Tech. A Guide to the Archaeology of Tomorrow, by Manfred Hamm; Hennessey & Ingalls (2000) [out of print]

Ellis Island: Ghosts of Freedom, by Stephen Wilkes; W. W. Norton (2006)

Industrial Ruins: Space, Aesthetics and Materiality, by Tim Edensor; Berg Publishers (2005)

Invisible Frontier: Exploring the Tunnels, Ruins, and Rooftops of Hidden New York, by L.B. Deyo and David Leibowitz; Three Rivers Press (2003)

Invisible New York: The Hidden Infrastructure of the City (Creating the North American Landscape, by Stanley Greenberg; The Johns Hopkins University Press (1998)

New York Underground: The Anantomy of a City, by Julia Solis; Routledge (2004)

New York’s Forgotten Substations: The Power Behind the Subway, by Christopher Payne; Chronicle Books (2002)

Underworld: Sites of Concealment, by Manfred Sach and Klaus Kemp, photographs by Peter Seidel; Hennessey & Ingalls (1997)

DVDs

Atomic Journeys, Welcome to Ground Zero, directed by Peter Kuran (Goldhil Home Media, 2000)

Echoes of Forgotten Places: Urban Exploration, Industrial Archaeology and the Aesthetics of Decay, directed by Robert Fantinatto; Scribble Media (2005)

Websites

gallery.pimprob.com/UE091006

www.clui.org/clui_4_1/shop/select.html [Center for Land Use Interpretation books list]

www.darkpassage.com

www.infiltration.org

www.jef.poskanzer.org/photos/archaeology.html [lots of links to other urban exploration sites]

www.modern-ruins.com

www.opacity.us

www.uer.ca