30 Years Of Amazing Pictures

Viewed in retrospect, the images that have appeared in American Photo over the years reflect a breadth of visual interest.

Viewed in retrospect, the images that have appeared in this magazine over the years reflect a breadth of visual interest, the product of an irrational exuberance for the art of photography on the part of our editors and audience. In choosing the images for this retrospective portfolio, we aimed to identify the special qualities of American Photo’s vision, to distill our ideas about photography into a small, potent sampling. Accordingly, the photographs you’ll find on the following pages are loosely grouped to explore ideas of information, identity, and illusion. There is also a sense of sublime inspiration to be drawn from this essential collection. Man Ray once said, “Of course there will always be those who look only at technique, who ask ‘how,’ while others of a more curious nature will ask ‘why.'” As always, we invite you to be curious.

A Sense of Time

Whenever I have seen this image, my thoughts have run to “The Streets of Laredo,” a song also known as “The Cowboy’s Lament.” You’ve heard it, no doubt.”I see by your outfit that you are a cowboy,” go the lyrics.

Clothes tell us so much about someone, though they can be misleading. Like photographs.

In this particular photograph, the clothes are but one of the clues to the man’s identity. His outfit says he is a cowboy, but it is the authenticity of the setting that tells us he is the real thing: I focus on the Budweiser cans stacked inside the cooler with the Coca-Cola emblem, and the palpable light.

Photography may find its purest meaning in its ability to stop time, but in its ability to define identities there is a power approaching that of literature. No master of prose, not even a Hemingway, could capture the telling detail of this scene as well as William Albert Allard has done in a single picture.

What we learn from the picture is not definitive, of course. This happens to be a documentary photograph, but I prefer to view it as a song. “Come sit down beside me and hear my sad story,” goes the song. I’m willing to pull up a stool and and listen. — Bob Schieffer

A Sense of Identity

When somebody asked Mathew Brady why he went to cover the Civil War, he said, “I had to go. A spirit in my feet said, ‘Go,’ and I went.”

I’ve always been partial to photographers. Those of us who write down words know we can always catch up with the story later; the shooters know they have to be there when it happens and stay until it’s over.

Mathew Brady’s images of Americans who were killed and wounded by other Americans haunt us still in a way no words ever can. Nor could words ever describe the cost of that war in the way Brady’s pictures did.

I didn’t know much about photography when I was a young newspaper reporter and I was sent to Vietnam in 1965. The day I left, the paper’s chief photographer, Harry Cabluck, gave me a Nikon 35mm camera, showed me how to focus it, and assured me I’d figure out the rest.

When I got to Vietnam, I came to know the great Eddie Adams, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Associated Press photographer. He showed me how to read a light meter and to set the distance on my Nikon at ten feet. Then he said, “Just don’t take a picture of anything closer than ten feet. The rest is just reflexes.”

So Eddie and I struck a deal. Eddie let me travel with him. I caught cut lines for him — wrote the captions for his pictures — and he taught me to take pictures. It turned out to be a lot more than reflexes, but he was a good teacher and I got pretty good at it, good enough to get through two levels of job interviews at Life magazine. But I was offered a job at the local television station back home in Fort Worth, Texas. It paid $20 a week more than I made at the newspaper. I needed the money, so I got into TV news. But it was during those days that I came to appreciate what photographers do. They were in the middle of the action; they were usually the ones who had the best feel for what was happening.

If photography has not changed history, it has helped us to better understand it.

From the horror of Brady’s images of the Civil War battlefields to the pure joy we saw on the faces in those celebrations at the end of World War II, from Eddie Adams’s shocking photo of the execution of a Vietcong soldier to the pride-inspiring picture of Marines raising Old Glory on Iwo Jima, from the horrors of Iraq to the great achievements in sports, photographs capture the moments that help us understand a time.

No one can say where technology will take photography in the future. What we do know is that every photograph begins with the courage and dedication of the shooter, the photographer who feels what Mathew Brady felt when he said, “A spirit in my feet said, ‘Go,’ and I went.”

Bob Schieffer is a correspondent for CBS News. — David Schonauer

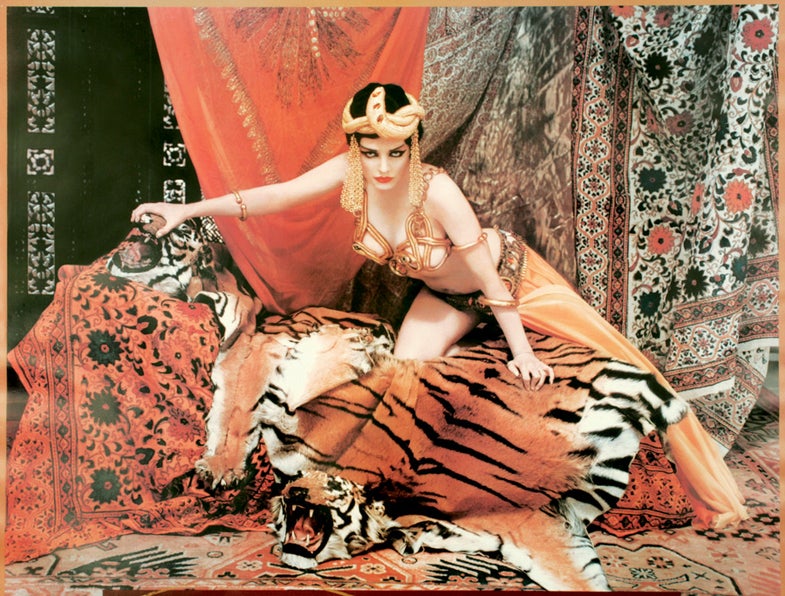

A Sense of Illusion

Photography made its reputation on reality, but it has made its living on illusion. Since the camera first showed a field strewn with cannonballs after the charge of the Light Brigade, or a dead Confederate sniper, we have tended to give photography the benefit of the adage “Seeing is believing.” And that belief, even when we know it makes no sense at all, gives a potent advantage to those who use photography to show us, in Jonathan Swift’s phrase, “the thing that is not.” If photojournalists have given us shock, the illusionists have provided awe.

Of course, all photographs are illusions, whether of a distraught migrant mother, a plump Parisian attempting to leap over a puddle, or a seductively posed movie siren. The human eye is capable of focus, but not framing. So the inescapable borders imposed by cameras — however honest the images they enclose — leave out far more reality than they take in. What was to the right or left of that Depression-era mother? Would the scene have looked different to us had we been there, instead of seeing what the photographer shows us? And what was Ansel Adams’s zone system if not a technique of stage lighting? The idea that we are seeing in a photograph life as it is is perhaps the hardest illusion to deny.

With lenses, lighting, and legerdemain, photographers have long created visions calculated to sharpen our appetites for everything from fashion to food, beauty to Buicks — dazzling us into wanting what we often don’t need. Even when we’re aware of the array of tricks that can glamorize everything from French frocks to French fries, some vestige of believing what we see in a photograph still clings to pictures made for advertising. We may be media savvy and spin cynical, but an image of an implausibly lovely woman in a casually draped gown on a chic sofa, with flattering light streaming through a window, can still make us think that those looks, and that luxe, are not too far from true.

The best photographers, whether working for money or the love of art (though the two need not be exclusive, as Irving Penn shows us so elegantly), take full advantage of the illusory power of the camera. An elephant, mysterious and fantastic as it seems to emerge from a diaphanous mist of fabric; mirror-image twins right out of Munchkin Land; a Doberman pinscher seeming to bite the beautiful arm that feeds it (and Harry Winston); a glamorous screen goddess pretending to be another screen goddess; a sextet of stop-motion pictures of a running woman, as similar and unique as snowflakes: These all have the resonance of dreams and can make us think we are seeing what is there, when what we see is nothing more or less than a photographer wishes us to see — inventions made by the eye for the eye, rendered counterintuitively convincing.

Some philosophies teach that there is no reality, that all is illusion. Looking at Joel Sternfeld’s haunting, poignant photograph of a burning house on a hill behind a farm market, the orange of pumpkins eerily repeated in the flames engulfing the roof, we see one of those moments when visual truth really is stranger than fiction, when realism merges seamlessly with surrealism. And despite our trust in the camera’s unbiased eye, it’s tempting to feel that what we are seeing is an illusion of an illusion. — Owen Edwards

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-001

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-002

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-003

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-004

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-005

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-006

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-007

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-008

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-009

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-010

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-011

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-012

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-013

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-014

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-015

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-016

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-017

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-018

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-019

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-020

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-021

30-Years-of-Amazing-Pictures-022