Glowing millipede genitalia give scientists a leg up in the lab

We've got a handy new imaging technique for defining millipede species.

Millipedes’ exoskeletons glow fluorescent shades of green, yellow, blue, and pink under ultraviolet lights––and so do their genitalia.

This chromatic phenomenon is common among arthropods––the group of invertebrates that includes millipedes, scorpions, spiders, insects, and some marine creatures––and scientists have been using UV lights to study scorpions since the 1950s. That’s where Petra Sierwald, an evolutionary biologist and associate curator at the Field Museum’s Integrative Research Center in Chicago, got the idea to open her drawer of millipede specimens and see which ones glowed in the light. The result was what ’90s black-light poster dreams are made of. It also proved to be scientifically useful.

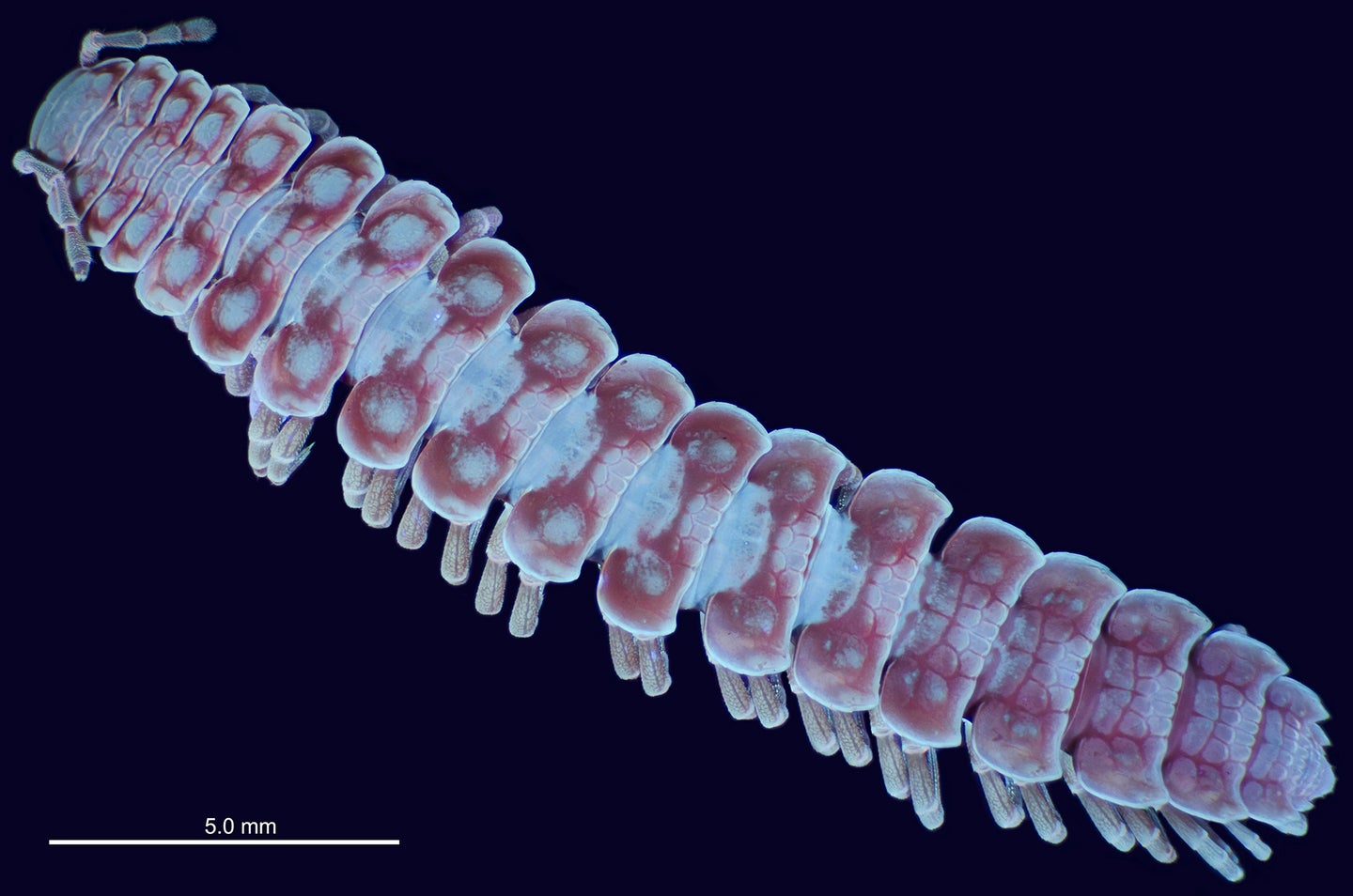

“Millipedes have had a tough time in research,” says Sierwald. “They’re hard to work with, some are too big for a microscope, and others are hard to see in detail because they’re really small.” But a new UV imaging method, described by Sierwald and colleagues in a study published Thursday in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, could help scientists quickly identify nearly-identical species of millipede by getting clearer views of their glimmering genitalia and exoskeletons. Both structures, commonly used to differentiate insect and arachnids, are unique to each millipede species and fluoresce, or light up, under UV lights.

There are over 12,000 existing millipede species. Being able to precisely define more of them—those lurking both in the wild and in museum storage drawers—is important for understanding the arthropods’ biology, and specifically how the sometimes invasive species function in different ecosystems.

When it comes to the glow, it’s the proteins in the gonopods––or reproductive organs––as well as bits of the exoskeleton called cuticles that reflect UV light back to the onlooker in the visible spectrum. Though Sierwald says they aren’t sure why exactly these millipedes glow biologically, she’s quite relieved at how easy and quick it could be to categorize species going forward.

RELATED: How scientists saw the ‘invisible’—and captured the first image of a black hole

The new method involves taking a series of images at varying focal lengths using a motorized lift that moves in teeny, tiny increments. Once the images are stitched together, the photos reveal minute details of a leggy creature, like the Pseudopolydesmus canadensis shown above. This species is on the small side, clocking in at roughly two-thirds of an inch long.

The blueish leglike structures in the images below are male millipede gonopods, and actually begin as legs. When male millipedes are in the equivalent of their late-teen years, the legs molt and reveal intermediate tube-like structures. Then, with one more shedding, the former walking legs morph into fully-functioning reproductive organs. Millipedes are blind, so their gorgeous gonopods go unseen by their mates, but the mysterious trait proves useful for scientists. The unique knobs and spikes along the gonad-legs, illuminated in a new (UV) light, reveal which species the millipede belongs to.