The Curious Cameras of the 3D TV Era

3D TV is dead and this crop of quirky cameras lies in its wake

We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

In the years surrounding 2010, 3D TV seemed like a big deal. Almost every manufacturer dove head first into making 3D panels and the often-goofy glasses that go with them. Here in 2017, however, 3D TV is completely dead with Sony and LG reportedly discontinuing their 3D offerings in 2017. They were the last of the major brands still in the space. So, while there are few people out there mourning the passing of an awkward era in home entertainment, it has left in its wake a collection of quirky cameras and camera accessories meant to augment the 3D experience.

Perhaps the most high-profile dedicated 3D consumer camera came from Fujifilm, a company without any real skin in the 3D TV game. I distinctly remember going to a lavish preview event for the Real 3D W3 camera held in New York’s Museum of Natural History.

The camera was actually a follow-up to Fujifilm’s original 3D model, the W1, but represented some pretty distinct upgrades, including a pair of CCD (!) sensors, each behind its own set of optics. This was no split optics setup, but rather a camera with two cameras built-in. It also had a parallax barrier 3D screen on the back, so you could see the images popping out at you without the need for glasses.

The Real 3D W3 seemed impressive for the time. Sure, the 3D screen on the back of the camera was reminiscent of those lenticular baseball cards that changed the picture as you tilted them back and forth, but you didn’t need glasses and there was a real wow factor about it. Plus, it was only $500, which wasn’t cheap, but seemed like a better deal if you had already bought a pricey 3D TV, which were sorely lacking for content at the time.

Despite its position as a 3D TV manufacturer, Sony actually took its time fully embracing the 3D camera wave. It first dabbled with a 3D Sweep Panorama mode, which used a camera with a single lens, and required the user to actually move the camera to capture a wide swath of the scene in front of it. In 2011, Sony used its massive CES press conference to announce the HDR-TD10 3D camcorder, which had “Double full HD” capabilities.

At the same time, it also offered up a 3D version of its Bloggie camera, which looked a bit like a chunky smartphone, but also offered 3D capture with less resolution for a lot less money.

Eventually, Sony added a feature called 3D Still Shot to its Cyber-shot cameras, in which the camera would take several photos in rapid succession and then combine them in the camera to create something somewhat similar to what you could expect out of a true stereo camera.

Panasonic delved deeper into the world of 3D image capture to augment is 3D TV business. The 12.5mm f/12 Lumix G 3D lens had two sets of optics attached to its interchangeable-lens cameras. It laid down two nearly-identical images onto the camera’s Micro Four-Thirds sensor.

In theory, this was a great way to bring 3D to a camera line. The lens was compact, relatively inexpensive, and didn’t rope you into buying a camera dedicated to a technology with a very unsure future. However, it had some severe drawbacks. The fixed f/12 aperture required tons of light and splitting up an already-crowded Micro Four-Thirds sensor didn’t help resolution or image quality.

The lenses are also much closer together than the human eyes, so the actual 3D effect wasn’t very pronounced, especially compared to the exaggerated 3D effects we were used to in the theaters.

You can still get them on eBay for less than $150.

Beyond its interchangeable lens option, Panasonic actually made a twin-lens compact camera called the LUMIX 3D1. It had a pair of lenses and image sensors, but used a standard 2D touchscreen for a display. As a result, you couldn’t even really see the 3D images you took until you hooked up the camera to a 3D TV. It was clear the camera was more of a 3D TV accessory because of that fact. The company also had a line of 3D camcorders like the Sonys, most of which were equipped with sizable dual-lens assemblies on the front.

Interestingly enough, Pentax has a longer history with stereoscopic imaging than most other big manufacturers. In fact, some of its early digital cameras in the Optio line used some old techniques to capture stereoscopic images that could then be viewed with a stereo viewer similar to the ones used in the film days.

The process included taking a pair of pictures, then the camera would combine them into a single file that you could print out and look at through a viewer. Pentax never really seemed eager to do more than that with 3D and it proved a good bet.

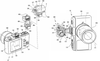

Olympus built a 3D capture mode into some of its compact cameras, which involved taking a shot, then using the screen as a reference to take another. It wasn’t very exciting, but it could have been a lot weirder. The image above is from a patent filed by Olympus for a camera add-on that would actually put a lens in the camera’s hot shoe. You could then shoot 3D images and footage with a normal Olympus camera.

Finally we come to Samsung. While the company was one of the driving forces behind the 3D TV movement, its 3D camera offerings weren’t very robust. Perhaps the most interesting entry into its 3D venture was the 45mm f/1.8 2D/3D camera lens.

When in 2D mode, the 45mm f/1.8 2D/3D acted as you’d expect a standard prime lens like this to act. In 3D mode, however, it actually had a transparent LCD inside that would flicker back and forth, blocking the right and left sides individually to create stereoscopic images. It worked basically the same way active shutter 3D glasses work.

It worked well, actually, but it wasn’t cheap thanks to all that extra tech inside, checking in at around $500, which isn’t cheap for a 50mm APS-C prime.

With traditional 3D gone, we now live in the era of virtual reality and the debate over its viability is similarly heated. And while the headset aspect of viewing VR is even more taxing than the old 3D glasses, the payoff is much, much greater. It will be interesting to see where we are in another five years.