When Subcultures Converge: Oliver Sieber’s Imaginary Club

For his latest book, German photographer Oliver Sieber appropriates two very different modes of so-called documentary photography towards a fictional...

For his latest book, German photographer Oliver Sieber appropriates two very different modes of so-called documentary photography towards a fictional end, using pictures of real people and places to form a complex portrait inside an “Imaginary Club.”

Seven years spent traveling the global punk, goth, skin, mod, rockabilly, psychobilly — you-name-it circuits has resulted in a mammoth 432-page self-published monograph (BöhmKobayashi/GwinZegal), which at first might appear like an encyclopedic survey of contemporary youth subculture and counter-culture around the world. That would be a colossal, almost absurd task, recalling Edward Steichen’s The Family of Man exhibition and undoubtedly befitting the book’s size, but Sieber says he sought nothing of the sort.

“A good record store, or a club, with good music can be like an island for me. Everywhere I travel I try to find those places,” he says. “Maybe in this way, yes, you can call it a self-portrait. It’s all my personal interests and preferences put together in my personal context.”

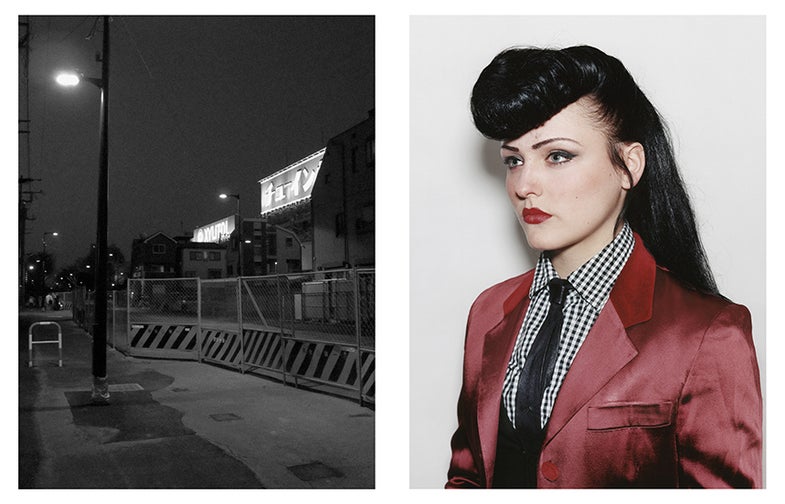

Within this meeting of the tribes, so to speak, there is also convergence of two distinct photographic subcultures. Half the book features formally restrained, typological color portraits in the tradition of the Düsseldorf School (Sieber’s hometown), which makes me think of a combination of Thomas Ruff’s Passport photos and the Straight-Ups pioneered by i-D magazine. Black-and-white snapshots of club, street and concert scenes are mixed in equal proportion. These images are rough, blurred and out-of-focus in the tradition of Japanese photographers like Daido Moriyama.

In contrast to Sieber’s earlier work, where he had considered themes to work around and planned for cumbersome equipment, with this he says he simply pulled aside anyone who caught his eye for a quick capture. “No more backdrops, no large format anymore, just a convenient camera and a small flash,” he says. “I also gave precise instructions and took only three or four shots.”

His subjects, met in places as disparate as Birmingham, Helsinki and Tokyo, come with a flurry of piercing, tattoos, patches, accessories and gravity-defying hair—what Sieber terms “stylecodes.” These are signifiers of otherness, identity not of a fixed definition, but related in opposition to the varied dominate cultures — the when and where — from which they hail. Pictured en masse and immersed in the many pages of this book, the far-flung subjects reveal themselves with some striking similarity.

“People often ask for more information about my work,” Sieber says. “I don’t like giving away too much detail, however, just some hints pointing out some directions to think about.”

Rather than marking his images with fixed, definitive captions, Siber includes a “Tweeted Encyclopedia” about the work with a directory of mostly vague hashtags for the subjects (i.e. #Cosplay #RolandBarthes #TheCure #HorrorPunk) which places the work into a fluid and interactive context.

“What I like about Twitter or other digital platforms is the possibility to connect your works with videos and music through links,” he says.

Those who encounter the work are left to decide which links to follow and what direction to choose when making meaning of the visual and textual signifiers. It is a sublime non-place Sieber shows us, which seems to exist somewhere in the interpretive space between the subject, artist and audience.