What’s Next for Contemporary Photo Collage

Forging a unified vision in a fractured society

Stripped down, collage is essentially the act of cutting and pasting images together. But add tools—a camera, Photoshop and an eye for composition, color and graphics—and you have a vehicle for abstracting memory or forging a unified vision in a fractured society.

In Cut/Paste, at Brooklyn’s Klompching Gallery, viewers are asked to get lost in the fantasy of photo collage art through the work of eight artists whose wide range of approaches to the medium are on display.

The show is woven together through the exploration of identity, be it self-identity or how perception surrounding the identity of others is formed. “What connects the photo collages in the show is an undercurrent of portraiture,” says curator and gallery co-owner, Darren Ching.

There’s the work of Cornelia Hediger, the most “traditional” of the group and the most highly crafted, who uses self-portraiture to construct personal narratives. Her signature is seen in the black outlines she makes around each cut image.

And Antony Crossfield who takes a psychological look at ageing and his own mortality by stitching together men of different ages in a manner that evokes the grotesque of Francis Bacon. You can almost feel the interiority of his subjects.

Bill Durgin composites several images of a figure and systematically erases portions of the images to distort the boundaries between the figure and the background, confusing the perception of visual hierarchy within an image.

But this exhibit is also a chance to give context to and a fresh look at a long-standing tradition of photo collage. Originating in a process called combination printing, Oscar Rejlander is credited with making the first of its kind in 1857. Titled, “The Two Ways of Life,” he spliced together 30 negatives into a single allegorical tableau to describe the choice between vice and virtue.

Ching explains that some of the most iconic photo collages came out of wartime Germany where artists influenced by the Dada and Bauhaus movements like John Heartfield, Grete Stern and Erwin Blumenfeld, among others, used the medium as a tool for political resistance in both fine art and commercial works.”“The social and political upheavals before, during and just after WWII saw the photo collage as an ideal expressive vehicle to shock and provoke—often politically motivated,” Ching says.

Since then, there have been many artists who’ve used photo collage, like Pictures Generation artists John Baldessari and Barbara Kruger, as a means for expressing the ubiquity of images and bold feminist statements, respectively.

Perhaps the contemporary resurgence of photo collage—as evidenced by the work of artists like Lucas Blalock and Sohei Nishino, among others—is no coincidence in a time where societies around the world are becoming increasingly divided along socio-political lines. The disjointed nature of the medium itself is highly symbolic. “In Western art, the Renaissance period was arguably the last time there was a cohesive art movement,” says Ching.

Several of the artists in the exhibit mine personal and art history through their works.

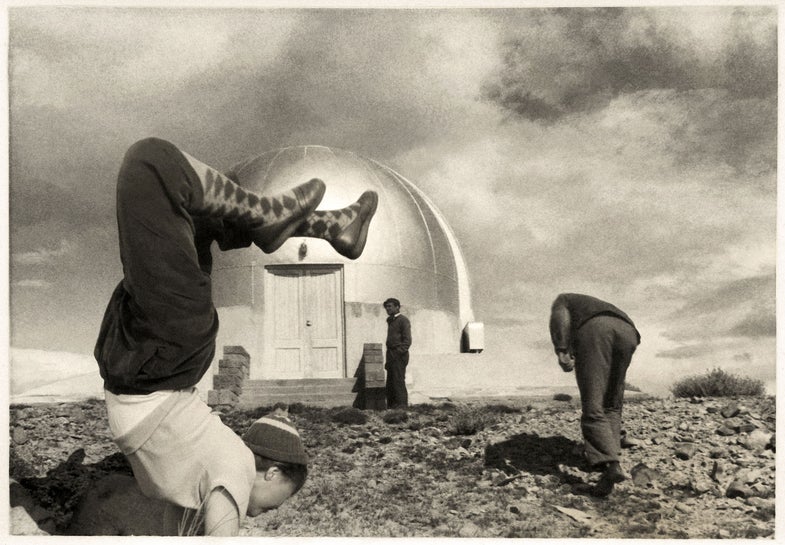

Peter B. Leighton, for example, is interested in the ways we epitomize the past, and so he works with vintage vernacular photography to seamlessly construct new images with found photographs. And within these new narratives, there is a kind of satiric sensibility and darkly comedic undertone that shines through.

The work of Marc Baruth pays direct homage to the landscape paintings of Peter Paul Rubens, who, like Baruth, was born in Siegen, Germany. He constructs pastoral scenes showing everyday German people at leisure.

Alma Haser references Cubist artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque with portraits in which she composites a photo of a physical origami shape from other photos she’s taken of the person over a portion of the face.

Collage is also a way for an artist to create his or her own visual language. Today, Ching says, “We’ve seen a lot of photographers using both traditional and digital tools, treating the photograph as an object, or constructing uniquely personal visions.” This may be in part because of the high bar that’s been set with the omnipresence of the straight photograph. “Many contemporary photographers are wanting to create unique works that connect to their individual sensibilities,” he explains.

Odette England uses a medical tool as a primer, layering the patterns of Ishihara ColorVision Tests for color blindness over family photographs, to talk about the accuracy or lack thereof of memory and how it’s influenced by photos and stories. The iconography speaks to the idea of the brain as a sponge.

Joana P. Cardozo uses everyday objects found in the homes of her subjects—which she views as being a direct reflection of their personality—to make “portraits.” The images are awash in a uniform color to maintain a graphic flatness which unites the disparate images.

Perhaps what gives the medium the most power are the idiosyncrasies inherent in each work. Photographers can “create messages through photography that they wouldn’t be able to do through a more traditional approach,” says Ching. “With the photo collage, the voice of the artist is more evident than in other photographic genres. It’s not passive, not just capturing images—rather it’s active, aggressive, imposing a viewpoint by restructuring visual information.”

Cut/Paste is on view at Klompching Gallery through February 18.