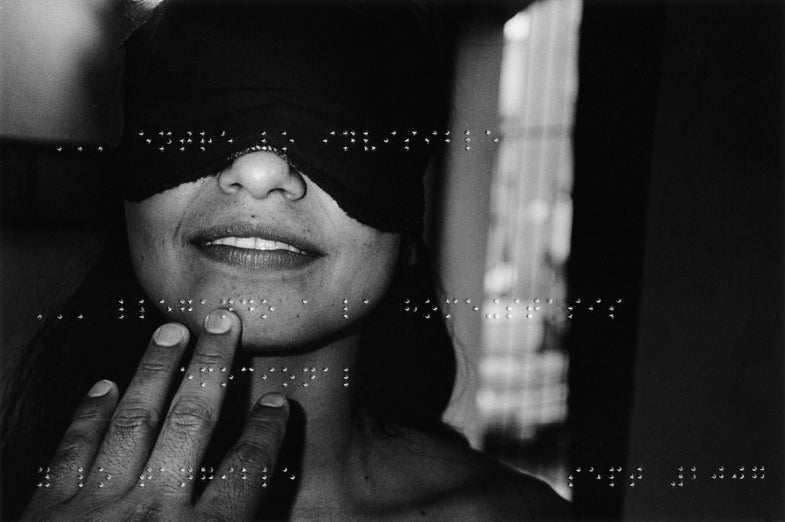

Blind Photography: The Heart of the Medium

Pressing the shutter: blind photography showcases visual art from unique perspectives

As a child Bruce Hall never understood why people were so excited about seeing stars. When he looked up at the night sky, he saw mostly darkness—maybe a bright spot where the moon was. Then one day, a neighbor helped him attach his box camera to a telescope and everything changed.

“He said to point it at a dark part of the sky, and open the shutter and leave it for a minute,” Hall recalls. When he finally saw the prints from that night, everything became clear. “I got results. That’s when I realized what could be done.”

Hall is legally blind due to an underdeveloped optic nerve, and can only see objects that are a few inches away. However, this didn’t stop him from pursuing a career as a photographer. Hall specializes in underwater photography and has had his work published by outlets such as National Geographic and shown in exhibitions around the world. As of March 2016, he was currently working on a project focused on his autistic twin sons.

Hall is also a member of the Blind Photographers Guild, a small group of photographers who have been working together for almost a decade to compete head-on with their sighted counterparts.

Hall met Pete Eckert and Alice Wingwall, the Guild’s other two members, in 2009 when their work was selected by curator Douglas McCulloh to be part of the traveling exhibition called Sight Unseen: International Photography by Blind Artists, which was on view at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

That exhibition is a way to showcase work from 13 blind photographers from around the world, and explore the unique perspectives they have that sighted people may not. It incorporates three-dimensional versions of photographs and touch-activated sensors that provide other information to viewers.

“I initially regarded blind photographers as an outpost on photography’s periphery, I assumed each image was, literally, a shot in the dark,” says McCulloh, the curator of the show. “That was a terrible misapprehension. Blind photographers operate at the heart of the medium; they are the zero point of photography. These artists occupy the pure, immaculate center—image as idea, idea as image.”

The purpose of the Guild and exhibitions such as Sight Unseen is essentially to bring the work of blind photographers into the cultural mainstream.

“Part of what we’re trying to do is break ground in the sighted world by showing what blind people can do,” says Eckert. “We’re standing on ability, not disability.”

The accomplishments of the Guild members are not insignificant either. Wingwall has traveled around the United States and Europe for her art, and is the subject of a documentary film. Hall’s photographs have been published by magazines such as National Geographic and his work has been shown at the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian, the Centro de la Imogen in Mexico City and the Flacon Arts Complex in Moscow, Russia. Eckert has also had his work shown around the world, from his home in California to exhibits at the Sejong Center in Seoul, South Korea and one of his images was chosen to be issued on a postage stamp by the United Nations in 2013.

Eckert, a trained sculptor, was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa, a degenerative disease that affects the retina’s ability to respond to light, at 26. He continued with his art for a while, but it soon became difficult to feel the smaller details in his work and he had to rely more and more on another person’s vision. For Eckert, who went on to earn his MBA and a black belt in taekwondo after losing his sight, that kind of reliance wasn’t ideal.

“I realized that I had to own up to the work being a collaboration or I had to find another method where sighted people aren’t a part of the process,” he says.

After stumbling on his mother-in-law’s old camera one day, he found he liked the concept of photography, and started working more in the medium. He values photography because it allows him to work alone. He says he likes to work with very large prints because he wants the work to be interesting from far away as well as up close.

“Sighted photographers go looking for a shot,” he says. “I go out with the end in mind. I’ll build the image with light.”

Bruce Hall, on the other hand, has a different approach. He often shoots underwater and recently he has been working on a long-term project documenting the lives of his twin nonverbal autistic sons, who are now 14 years old. For that project he has learned to follow the lead of his spontaneous subjects.

“My strategy for photographing the boys is to be ready all the time,” he says. “I always have a plan about what I’d like to capture but that usually changes.”

Practically speaking, Hall is unable to see most things unless he can get very close to them. But if he prints out photos or views them on a screen such as an iPad, the details come out. Essentially, he uses photography to see.

“I love technology, it’s a friend to me,” he says. “There are things I’m able to do now that I wouldn’t have been able to in the past.”

Like Hall, Wingwall loves what new technology enables her to do, but hasn’t forgotten the skills she learned when she first got serious about photography as an art form. Having studied art, architectural history and sculpture in the United States and Europe, she was helping start the sculpture program as an assistant professor at Wellesley College when she bought her first camera. She started off sharing a darkroom with other staff and studying a syllabus created for photography students.

Shortly after she began working in the darkroom she started to slowly lose her sight due to retinitis pigmentosa. Technology ended up being her saving grace.

With roughly ten percent of her retinal slivers left, she made what she calls “two great decisions“: buying a Canon EOS camera equipped with autofocus and going through guide dog school with her first dog Joseph.

She still sometimes uses film when she wants to do a double-exposure, but generally, the automatic focusing, exposure and other settings on the Canon Rebel work really well for her, especially for more spur-of-the-moment photographs.

“I can still perceive brightness, even if I don’t see it,” she explains. “You just have to think about it.”

Ultimately, all three photographers are quick to point out that their work has been well-received on its own merit, rather than on the novelty that they are blind and making visual art.

“I’m very tired of people asking how someone can take a photograph when you’re blind,” Wingwall says. “All you have to do is press the shutter.”

Sight Unseen: International Photography by Blind Artists will be shown at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg, Manitoba until Sept. 18