W. Eugene Smith’s Time in The Jazz Loft

An in-depth look at life in the loft culled from 40,000 images

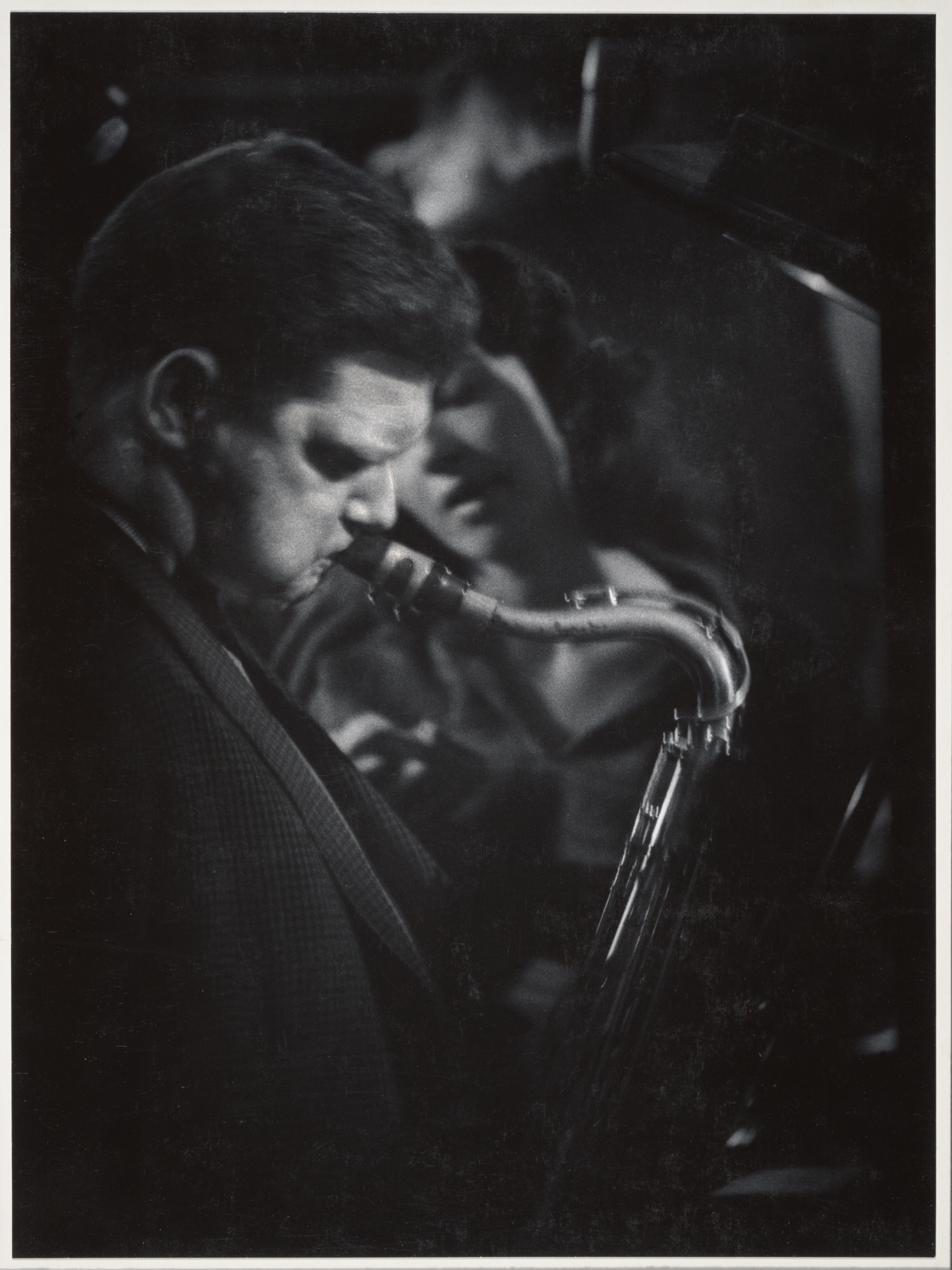

Thelonious Monk and the Monk Tentet in rehearsal, 1959

The many sides of W. Eugene Smith—revered photo essayist, combative control freak, free spirit, obsessive workaholic—merge seamlessly in Sara Fishko’s stunning new documentary, “The Jazz Loft According to W. Eugene Smith”, which recently screened at DOC NYC. The film spotlights the action at Smith’s loft, a darkroom-turned-studio hangout for New York City’s jazz icons between 1957 and 1965. There Smith shot and taped such musical greats as Thelonious Monk and Zoot Sims, as well as artists like Salvador Dali and Cartier-Bresson. Smith’s photos and sound recordings make up the bulk of “The Jazz Loft”, but Fishko augments them with interviews and archival footage to give a complete picture of Smith’s life before, during, and after the loft.

Smith rose to prominence with such LIFE magazine photo essays as “Country Doctor” (1948), “Spanish Village” (1951), and “Nurse Midwife” (1951). From a photojournalistic perspective these essays revealed an uncommon sense of personal empathy. Aesthetically, they employed a unique, painterly approach to the use of light, which not only became Smith’s hallmark but also exemplified his exacting standards in the darkroom. According to the new documentary, he would pop amphetamines to work for days on end, using up boxes of printing paper and potassium ferricyanide to produce one “acceptable” print. “It was perfectionism, but it was also a very strong desire to be able to control what he did,” says Fishko. One of the highlights of “The Jazz Loft” is rare archival footage of Smith’s hands under an enlarger’s lens, dodging and burning, ghostly and godlike as they expertly manipulate light and time.

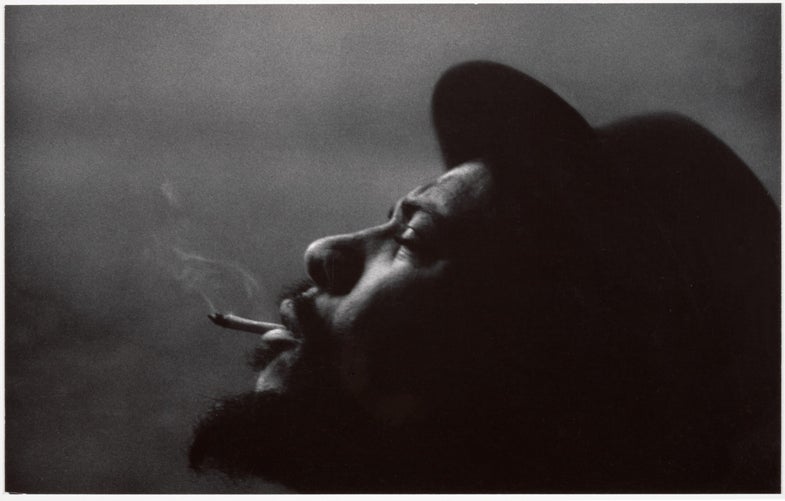

Zoot Sims

Smith was living in the suburbs, but he desperately needed to be part of the New York City scene, where the iconoclastic vibes of Miles Davis, Willem de Kooning, and Allen Ginsberg mingled in a general give-and-take of mutual creative resonance. In 1957, Smith left his home and family to move into a loft at 821 Sixth Avenue—a filthy, chaotic building populated by painters, photographers, and musicians, where Smith could devote himself utterly to his work without the distractions of family life.

Much as LIFE photographer Gjon Mili had done in the ’40s, Smith opened his loft to jazz musicians looking for a place to play after hours. “Eugene was a voracious consumer of music—on a level where he couldn’t get enough—so when his place filled with musicians, it was a natural fit. It kept the fascination going,” Fishko says. Smith hot-wired the building for sound and began recording everything: rehearsals, twelve-hour jam sessions, radio broadcasts, casual conversations, as if his artistic vision could no longer be contained in one medium alone. His favorite was saxophonist Zoot Sims, who, like Smith, would stay up for days doing nothing but work on his craft. “Eugene felt a kinship with people like Zoot, who were such naturals and so good at what they did that they didn’t want to do anything else but that, with other people of like mind and like skill,” Fishko asserts.

Thelonious Monk rehearsing in the loft, 1959

During his years in the loft, Smith shot 40,000 photos and recorded 4,000 hours of material. The crown jewel of the collection, according to Fishko, is the material Smith shot over three weeks in 1959, when Thelonious Monk and Hall Overton arranged, then rehearsed, Monk’s famed concert at Town Hall. “Eugene really knew something important was happening then,” says Fishko. “And he covered it like a journalist. He wanted to capture every bit of it, that sense of ensemble creation, that relationship between Overton and Monk, and how thrilled the musicians in the tentet were to be there.” Under Fishko’s brilliant direction, the Monk-Overton sequence is also the crown jewel of the film.

“The Jazz Loft According to Eugene Smith” grew out of a ten-part radio series on Smith that Sara Fishko produced for WNYC in 2009 after spending years with the photographer’s vast archives. When American Photo asked Fishko how she felt about Smith, she replied, “Even now, after doing the radio series and the movie, I’m still fascinated by him as a person—but also because he embodies a midcentury American creature who was torn between the conformity that was being demanded of him and a very, very strong, passionate creative urge.” Between Smith’s creative urge and Fishko’s fascination with it, “The Jazz Loft” is a thrilling view.