Story of the Shot: Gregory Heisler’s Boston Marathon Tribute Cover Photo for Sports Illustrated

For the one-year anniversary of the bombing at the Boston Marathon, Sports Illustrated planned a special cover, which would include...

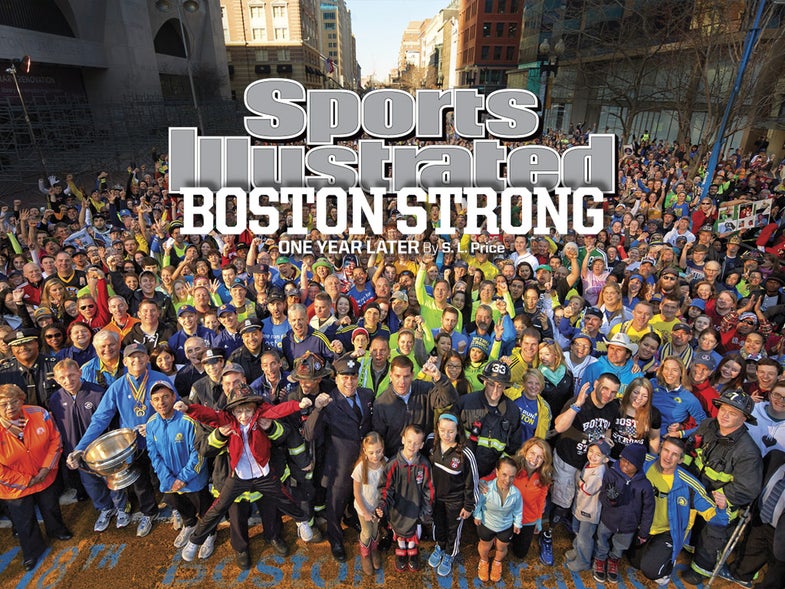

For the one-year anniversary of the bombing at the Boston Marathon, Sports Illustrated planned a special cover, which would include roughly 3,000 Bostonians posed near the site of the tragic event. Veteran portrait photographer Gregory Heisler was tasked with getting the shot. Here’s how he put it together.

Sports Illustrated Boston Strong Cover

Who came up with the concept for the shoot?

I think the idea was generated by Chris Hercik, who is the creative director at Sports Illustrated. I received a call about it earlier that week. Then, Brad Smith, the photography director at Sports Illustrated, sent me an email about this assignment. He didn’t say what it was, but he said that it was going to happen on that Saturday.

That seems like a pretty tight turn around for such a big shoot.

Sometimes that’s the way things come together. I was available and excited to work with him, and I decided to do it. Then, he told me what it was: a portrait of about 3,000 people standing in the middle of Boylston Street right by the finish line of the marathon.

So, they had a pretty clear vision of what they wanted when they contacted you?

it was really about the citizens of Boston coming together. They wanted to run it as a cover and do something inside as well. He said to me that it wasn’t a technical kind of picture. It was more about being able to get a response from the crowd. It was going to be something to pull it together logistically. I was excited.

How long did it take to prep the whole thing?

We went down there on Thursday night and Friday morning we scouted the location at about the time the shoot was going to be. It was around 7 AM. It turned out to be fruitless because it was raining that day. It was good to see it and get a bead on how big the space was and how many people were going to fit in there and where I would need to be.

We spent the rest of that day pulling the pieces together. There was a cherry picker with a little basket that we’d be shooting from and I wanted to physically take a look at it so I could see where I could put my cameras and how much room there actually was. They vary quite a bit. In this case, the railings were square in cross-section, which is good because you can put little clamps on them and they won’t rotate. Little things like that make a big difference. That’s why you do that kind of scouting.

There has been some debate online about how it was lit or if it was lit at all. How do you light that many people?

I’m a bit of a lighter. It’s something I really enjoy and I think it makes a big difference in setting the tone of the picture. We weren’t sure if it was going to be raining the next morning or what. It was a mixed forecast and I didn’t want a gray picture. The picture is supposed to be very upbeat and optimistic–a celebration of Boston’s resilience. I had the idea of casting a beam of light across the crowd so it would look like early morning sunlight.

What gear did you use to light everyone?

All we used to light up that entire crowd were two Profoto heads. They were battery-powered 7Bs. They’re 1200 watt strobes and we had them powered down to about half-power.

All they’re supposed to look like is the sun, so we didn’t need soft boxes or umbrellas or octobanks. The sun is a little dot in the sky that’s 93,000,000 miles away. It’s a hard light. Profoto makes a thing called a narrow-beam reflector, which is a highly-polished parabolic reflector. It throws a very concentrated beam of light. It’s like a grid spot, but instead of throwing away light, it concentrates it. It’s like a satellite dish.

From one side of the street, all the way to the other side of the street, I was able to feather the light and throw it all the way to the other side of the street. I was within a half-stop of F/8 all the way from one side of the street to the other. It was almost perfectly even.

It’s like you’re making a laser beam.

It is like a laser, yeah. What happens is that if you’re really close to it, but you’re off-axis, you’re just getting a little bit of spill. If you’re really far away, but you’re right in the focus of the beam, you’re still getting the same meter reading. I’ve done it before–not with 3,000 people. But, to me, that reflector is like the secret weapon in the Profoto lineup. It’s an amazing tool.

So, it’s just two light heads?

I had another light about a half a block away doing the same exact thing on the back half of the crowd. It wasn’t like I had a main light and a fill light. They were both doing the same thing in different areas. I had a half CTO warming gel on the light, to make it feel like morning light. If the sun is low enough in the sky to mimic where those flash heads were, it would have been warm.

If you see the same picture without the light, it still looks cool, but it looks sort of dead. When the flash goes off, it’s like it picks out every little face in the crowd.

Heisler Boston Strong Cover

Heisler Boston Strong Cover Lights

Using two hard lights for a crowd that big isn’t necessarily something I would have come up with. I’m pretty sure I would have just gone looking for a 400-inch umbrella to try and cover everyone.

I think that would be most people’s inclination. You’d try to get 20 octobanks lined up along the front or 10 on each side to really light the crowd. But, in the end, As much as possible, I try to take my lighting cues from what you might actually find in a location. And in this case, it would’ve been the sun.

The crowd was actually totally in the shade. We were being shaded by a building. If you look in the distance, like a block away, the light hitting the buildings back there is coming from the exact same angle and it’s the exact same color as the strobes. It just makes sense.

When did the people start showing up for the shoot?

There was already a bit of a crowd when we showed up at 6 AM. Some people had been standing there virtually all-night. They wanted to be in the front. They were really enthusiastic. The lift showed up around 7 AM, which is when the street was closed.

Who did you have helping you out with all the logistics?

I was working with a print producer on the set, Michelle Doucette, and she produces still shoots. She helped me secure the location, get the lift, and all kinds of other stuff in terms of organizing the shoot. The folks at Sports Illustrated had done a lot of the heavy lifting with the mayor’s office already. Brad Smith in particular, I know, jumped through hoops to make it happen.

We really took our time. I had a really specific plan laid out of how I wanted to light the crowd and the lens I was going to use. I actually called Canon just to inquire what the sharpest wide angle lens was in their line-up. They said it was the 17mm tilt-shift because it has to cover such a wide circle when it moves around. I wasn’t planning on tilting or shifting, so I would definitely be shooting in the sweet spot at the middle of the lens. I rented a few extra primes, just to be sure. I also got ahold of a 70-200mm and a 100-400mm just to pick out pieces of the crowd for inside the magazine.

Did you consider using medium format for this picture? It seems like the kind of situation where all that resolution really shines.

Years ago, I would’ve done a picture like this on 8×10 film for sure. And I don’t think it would’ve been near as sharp as this cover was. We had talked about whether it was worth it to shoot medium format. We agreed that for the purposes of the cover, there would be nothing gained. The halftone dots limit what resolution you’re going to see anyway. What’s amazing is that the cover is a vertical crop of a section of a horizontal frame. I shot it with a 5D Mark III. That’s why there’s no real distortion on the cover, even though it’s shot with a 17mm lens.

How long did the actual shoot take?

Literally the first frame I took with the lights flashing, we were kind of done. It looked exactly like I wanted it to look. That doesn’t always happen, but this time we were on the money. It looked great to me. From there, it was just about maneuvering a little to get it really perfect. It took about 10 minutes.

Once everything was set-up, the mayor showed up at about 8:15 and he popped in at the front of the crowd and we just started taking pictures. I don’t think we shot for five minutes. It was really quick.

How did you keep everyone’s attention in such a big crowd?

As soon as I got up in the basket, I had a bullhorn and I immediately started talking to the crowd. I wanted to get their attention and get them focused on me–on the picture. As much as you can kind of develop a rapport with 3,000 people, I wanted to have a connection with them.

I’ve had my picture taken for many different reasons and occasions as a member of a group of people. What happens a lot of the time is that the photographer is taking pictures up on a ladder, but they don’t’ really talk to you much. They’re fiddling with the camera and looking at the screen and that kind of stuff. You’re left out there wondering what you’re supposed to be doing. I was very clear with this group and basically didn’t shut up the whole time.

The bullhorn is a powerful tool in that situation

It is. I had an idea the night before that I should get a bright red jacket or rain coat. I thought I should be wearing something bright so that the crowd could easily see me and they know where to look. If you’re half-a-block away and there’s a guy up there wearing a black jacket that’s not going to help anything. But, if there’s a voice coming from a bullhorn and there’s a friendly red dot out there, it’s easy to focus. it ended up being really helpful, even if it sounds kind of dumb.

What else can you really do as a photographer to try and engage that many people?

I was using a cable release because I didn’t want to be looking into the camera. That’s something I do a lot for portraits anyway. It’s a hold over from shooting large format. You can develop a rapport with somebody much faster if you’re looking them in the eye than if you have your eyeball smashed to the back of the camera. Once I get all the technical stuff out of the way, then all my attention is on the crowd. That’s where it needs to be.

Going back to something you said before, is it typical that a publication will hire you for a shoot before they really tell you what it is?

It’s a leap of faith [laughs]. But, it’s actually a leap of faith on both parts. You’re hoping it’s a great project and they’re hoping you’re not going to screw it up. I think it’s funny because if they told you what the assignment was and then you didn’t take it, then it’s like you don’t find the assignment interesting enough. It gets a little weird.

They also don’t tell you because they’re very protective. They don’t want the story to get out.

Does the existence of social media make that more difficult?

I’m not a big social media person at all, unfortunately. Social media can work for you or against you. For example, Sports Illustrated used social media to gather this crowd. That’s a great thing. But, what I think of as an abuse of social media would be if I got the assignment and immediately started Tweeting about how I had a great Sports Illustrated assignment with 3,000 people. A lot of photographers do that and that’s blowing a confidence a little. It takes the thunder out of their achievement of making this thing happen. I feel like the first time people see this, it should be when the magazine comes out. They shouldn’t hear about some dopey photography tweeting it.

It seems like it’s getting harder to keep anything close to the vest.

I’m really specific with my assistants. I tell them that they’re not to talk about shoots. That’s not what it’s about. I don’t make them sign NDAs or anything, but it’s a professional courtesy to keep this to themselves until it comes out.