Provoke: Beautifully Rough, Blurry, Out of Focus Japan

One of the greatest losses in photography with the waning of the era of film is the room for error....

One of the greatest losses in photography with the waning of the era of film is the room for error. Film is a brilliant but fickle medium, and any time a photographer releases the shutter on an analog camera, she or he opens up a vast space for one of the greatest elements in the process of creating Modern art: chance. Indeed, it wasn’t until apps came along adding distortions like artificial light leaks to our precise digital images that mobile photography really gained a prominent place in the visual culture. With film too, errors can be anticipated and manipulated, of course, but every once in a while an imperfection or ‘mistake’ comes along that’s so unpredictable beautiful, it makes it into the museums.

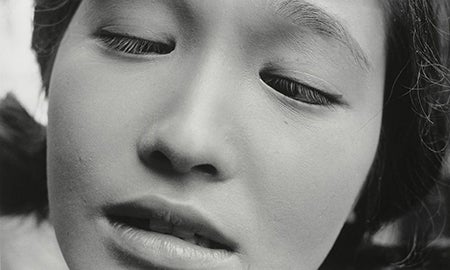

This sensibility is best captured in the work currently on view in “The Provoke Era,” at the Crocker Art Museum in California. Featuring Daido Moriyama, Shomei Tomatsu, Eikoh Hosoe and others, the exhibition showcases post-war Japanese photography from the collection of SFMOMA, technically ‘flawed’ documentary work with tremendous symbolic and emotional resonance. “Saturated to the point of looking wet, content savagely abstracted, and forms leaden or hallucinatory,” one writer described it for the MoMA blog.

The show’s name comes from the short-lived though hugely influential journal of photography called Provoke. Founded by the renowned Takuma Nakahira in 1968, the magazine captured the tumultuous period of social upheaval and waning traditions in post-World War II Japan through subversive imagery—”Are, Bure, Boke,” translated: rough, blurred, and out of focus. As the nation grew into an economic superpower through the 1960s, Provoke offered an alternative vision of society in contrast to the straightforward, glossy imagery of commerce.

“Today, when words have lost their material base—in other words, their reality—and seem suspended in mid-air, a photographer’s eye can capture fragments of reality that cannot be expressed in language as it is,” the editors wrote in their opening manifesto. Concurrent with the rise of New Journalism, Provoke rejected the classic ‘straight’ style of documentary photography in favor of a more expressive, subjective mode. They offered, instead, “provocative documents of thought,” without the constraints of narrative and conventional logic.

The sense of alienation and nihilism in the work should not however be mistaken for meaningless. “Their dark urban scenes are punctuated by bright flashes of light that indirectly reference the immediacy and violence of the bomb,” Lisa Sutcliffe, curator of an earlier iteration of the exhibition at SFMOMA, told Japan Exposures in reference to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Though the magazine ceased publication after only three issues—and as Sutcliffe concedes, it was a total “boys club – male artists, publishers, etc.” with none of the nearly 100 prints featured in the show made by female photographers—it nonetheless inspired generations well into the digital age, from Jacob Aue Sobol to Rinko Kawauchi, to the countless others, amateur and professional, contributing daily to this Flickr-hosted tribute group.

“The Provoke Era: Japanese Photography from the Collection of SFMOMA” is on view at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, Calif. through Feb. 1, 2015.