Portraits Document The Effects of Sexual Violence In The Congo

When Sarah Fretwell dove into the heart of the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2010, her only plan was to...

When Sarah Fretwell dove into the heart of the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2010, her only plan was to cover a story, not to change the world. “I didn’t understand when people said they had a calling,” Fretwell says, looking back on how her journey to the DRC to document survivors of sexual violence turned into the Truth Told Project, an ongoing multimedia series. “This topic somehow stayed with me.”

What began as a 50-day journey turned into a life-changing encounter with the women and men of this war-torn region plagued by mass killings, conflict and rampant sexual violence. According to data from a 2011 report in the American Journal of Public Health, in the DRC a woman is raped almost every minute, a rate even higher than previous UN estimates—and a problem that has only recently received attention in international media.

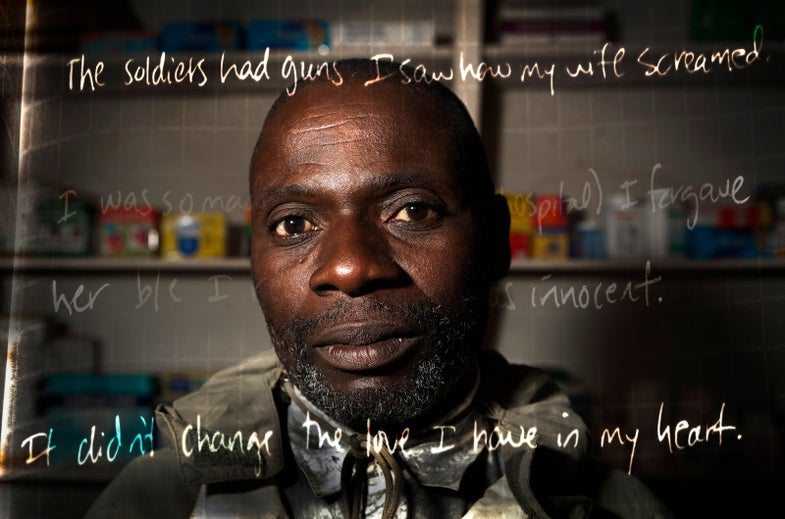

With her camera in tow, Fretwell delved into the women’s everyday lives as they recounted their ordeals and confided their hopes. The result was a documentary that combines haunting portraits with fragments of handwritten interview notes, all pointing to a larger story of conflict, a conspiracy of silence and survival.

Tackling gritty circumstances in areas of crisis was not new to Fretwell. The 35-year-old based in Santa Barbara, California, had reported on displaced Eritrean refugees, women’s rights in Haiti and child survivors of land mines in Cambodia; one of her photos of street children there won first place in Digital Photo Pro magazine’s Best Emerging Professional Photo Contest in 2006. When she learned what was going on in the DRC, she was compelled to act.

“I’m a fan of [independent news show] Democracy Now! I would listen to the audio stream every morning while working,” she recalls. “One day I heard a snippet about villagers in the Walikale region who had been held hostage. More than 200 women and girls were raped repeatedly by rebels, or so-called rebels, without any intervention. I was outraged—and I couldn’t fathom why the world hadn’t made a bigger deal of this.”

Seized by a familiar sense of purpose, she could only follow her instinct: “I decided to take a leap of faith and buy a ticket. I just knew I had to go.”

In a serendipitous twist, Fretwell was introduced by a friend to Amy Ernst, a freelance journalist who was working with CoPerma, a humanitarian nonprofit of farmer-businessmen based in the North Kivu region, to help victims of rape and demobilized child soldiers. The NGO helped Fretwell secure a visa into the notoriously insular nation.

Fretwell and Ernst put out the word through CoPerma that they wanted women from the surrounding area to come and share their stories. In a culture where trauma is commonly accompanied by silence and shame, the gesture was unique and, Fretwell recalls, cause for trepidation: “I remember riding on the back of Amy’s motorbike to the first set of interviews and thinking, ‘What if no one will talk to me?’”

To her relief, the first outing was an immediate success, with triple the number of women expected lined up ready to share their trials. It was an act of generosity, but also a leaden charge for Fretwell, who had to rethink her approach.

“I recall one particularly difficult interview with a girl who was a minor. She must have been about 15. I really wanted to convey her story, but also maintain her privacy. That’s what first led me to experiment with layering text, so that her identity wasn’t immediately recognizable but she was also very much present. I posted one of these first images on my blog, and someone working at the National Museum of African Art at the Smithsonian saw it and encouraged me to continue.”

The text eventually became a pivotal aspect of her image making, providing a written record of her subjects’ testimonies. As these came together, so did the Truth Told Project (thetruthtold.com), an ambitious undertaking that seeks to place these issues on a worldwide platform.

It’s working. This year Fretwell presented at SXSW Interactive and has spoken at numerous human- and women’s-rights summits; she’s now partnering with the Responsible Sourcing Network to raise awareness about how the tech industry’s reliance on the DRC’s rich mineral deposits helps fund armed groups and hinders peace.

The Truth Told Project now encompasses portraits and landscapes, interviews, journals, blogs and video and has been exhibited at the Contemporary Arts Forum in Santa Barbara and the Walk to End Genocide event in Los Angeles. In August her work was shown at Human Rights Watch’s second annual “Art with a Heart” event, which focuses on global humanitarianism in Eastern Africa. Plans are also in the works for a documentary short. As it evolves, Fretwell says her mission remains the same: “This is not over. This is still happening every day, and that has to stay at the forefront.”

For more on the Truth Told Project, check out this video.