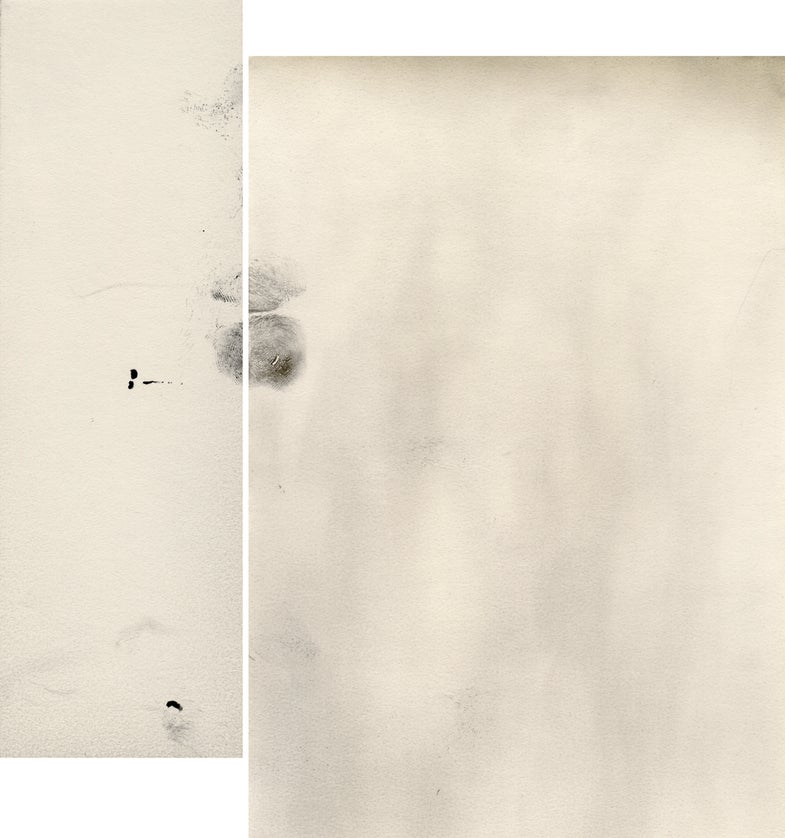

Photographic Paper, Decades Past Its Expiration Date

At Paris Photo, I met a woman who is doing research into the “materiality of photography,” or in other words,...

At Paris Photo, I met a woman who is doing research into the “materiality of photography,” or in other words, the physical properties of photographs. She’s been working with photo-preservationists, restorers and chemists to learn more about photographic paper, which is not—as is all too easy to forget in this age of screen-based image consumption—a simple flat surface. Instead, it’s made up of different layers, and they react in different ways to different conditions of light and temperature. Alison Rossiter, an American photographer living in New Jersey, is doing detective work that would fit in here. I also found her work at Paris Photo, where she was represented by two galleries. To make these images, Rossiter (who, not coincidentally, has experience in photographic conservation) located sheets of undeveloped photographic paper from the early 20th century, then developed them herself. The result is a strange, almost haunted series in which we see the fingerprints and dust left behind over the course of decades.

Looking at these photos, it’s tempting to make a quasi-dramatic statement, like “what we are truly seeing here is the raw trace of time.” In a way, though, isn’t that more or less accurate? In some of her other works with these expired materials, Rossiter has played with their development more actively, but here she’s developed them in a “straight” way, leaving you only to “see” the effects of time on the paper itself. We could think of these re-developed pieces of photo paper as a clear-headed exploration into the early days of photography. What she’s doing is in correspondence with the early camera magazines we’ve been featuring, or the work of Daisuke Yokota, who has tried to introduce similar distortions into his photos, in a natural (but, obviously, sped-up) way.

It’s a little odd to show these images online, because they lose all of the physical characteristics that were really there on the wall when I saw them. This is true of any photographic image when it’s displayed online, but it seems especially true in this case. Looking at Rossiter’s images, it’s easy to wonder what will happen to the photos being printed today.