Photo Mural Displays Throughout History

Photo Mural displays bring larger-than-life appeal to photographic art

Does bigger mean better? Several exhibitions in New York City, including “Richard Avedon: Murals and Portraits” at Gagosian Gallery (on view until July 27) and “Gordon Parks: 100 Years” at the International Center of Photography (on view until January 2013), make this an interesting time to explore that question and view a remarkable photo mural or two.

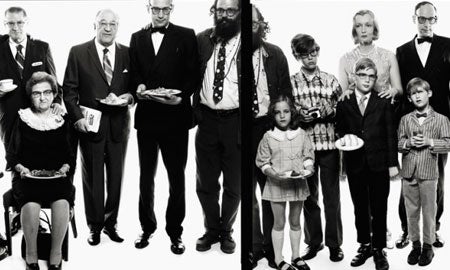

Avedon put the age-old adage to the test with his larger-than-life prints, which allow the viewer a chance to get up close and personal with iconic people staged on stark white backgrounds. Measuring in at up to 35 feet wide, and comprised of as many as five panels each, Avedon’s four photographic murals on display at Gagosian Gallery, made between 1969 and 1971 with his signature 8×10 large format view camera, are monumental in every sense. We see a unique perspective of the Beat poet Allen Ginsberg and his family, appearing to invite us to dinner; we are eye level with Andy Warhol and his crew of clothing-optional muses and collaborators at the Factory; we can almost feel the textures in the clothing of Abbie Hoffman and the late-1960s political radicals known as the Chicago Seven; and each line, each wrinkle on the faces of the Mission Council, the U.S. government team responsible for no less than waging the Vietnam war, is intimately revealed.

The Mission Council, Saigon, South Vietnam, April 28, 1971

If you visit the ICP for the Parks installation, you’ll see a 20 by 30 foot photo mural of his iconic 1952 image, “Emerging Man,” as part of the centennial birthday exhibition of the artist.

Installation view of Gordon Parks’s “Emerging Man.”

And the photo mural’s prevalence today is not limited to vintage work. The traveling Cindy Sherman retrospective (now on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) highlights her recent photomurals from 2010, works which function as monolithic entrance points into her photographic oeuvre. Standing at 18 feet tall, made up of 25 individual panels plastered to the museum walls like wallpaper, these are the artist’s largest works to date.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled (2010)

It seems like everyone is noticing the increasing size of the photograph. Rounding up six of the best contemporary photographers for the The Times U.K. recently, W.M. Hunt writes: “Twenty years ago the argument about photography was that it was supplanting painting in terms of scale. Based on my recent experience, I will report that photography seems to be chasing after architecture.”

If photography mounted as street art on large buildings counts, then the conjecture might just be true. The French artist JR, who installs large-scale portraits on buildings around the world, has recently shot to prominence. His works (installed in places like a violent Rio de Janeiro shantytown and on the Israeli West Bank Barrier) have become mouthpieces for larger political and social issues.

Meanwhile, Thomas Demand’s c-print of the interior of the Fukushima Daichi power plant, Control Room (recently on view at Matthew Marks gallery in New York City) registers at just over 78 by 118 inches. Andreas Gursky’s 73 by 143 inch print of the River Rhine, Rhine II, made headlines last year when it became the most expensive photograph ever sold (at $4.3 million). And the recent exhibit “Mitra Tabrizian: Photographs” at Leila Heller Gallery shows the British-Iranian photographer and filmmaker confronting the viewer with commanding mise-en-scenes: at up to 10 feet wide, the large-scale photographs, taken in Iran and England, evoke seemingly ordinary yet coldly staged juxtapositions in environments as diverse as office buildings and the Tehran desert.

City, London 2008

Though the exceedingly large photograph is enjoying renewed acclaim in the art world–as a means to construct a new layer of reality, to act as a strikingly confrontational banner, or to emphasize a political, social or commercial agenda–the photographic mural is nothing new.

As photo-sensitive paper evolved to accommodate larger sizes, true photomurals first came into use as a replacement for the traditional (and more expensive) painted backdrops in Hollywood. The mural was also used for the purpose of interior decoration and advertising in the form of billboards, such as with the Kodak Coloramas that were touted as “the world’s largest photographs” when they appeared in Grand Central Terminal in 1950. The large-scale color advertisements—measuring 18 feet by 60 feet—depicted quintessential American life and were on display for four decades (1950 to 1990). They will return to Grand Central on July 28 for a special exhibition.

A Visit with Santa – Donald Marvin

In 1932, the line between advertising and fine art was blurred for the first time when the Museum of Modern Art in New York hosted its first photographic exhibition, “Murals by American Painters and Photographers”, featuring photomontages by Berenice Abbott and Maurice Bratter. In the exhibition catalogue, curator Julien Levy—also a prolific art dealer and early proponent of fine art photography—describes his thoughts on the innovation of the photomural as modern art:

“It is difficult to stretch a single, simple photograph over a large space and maintain interest, but it is dangerous to enlarge a complicated negative, as the photographer has little control over the minor bits of his picture, and just as the peculiar virtues of a photograph are dramatized by enlargement, so are any faults equally exaggerated.”

Levy may have warned us of the difficulties of enlarging a negative, and the drama that ensues when a small portion of a photograph is revealed in large proportions. But, as digital technology continues to develop and images maintain clarity at ever larger scales, we may be seeing even more of an increase in photography trumping painting and sculpture as a genre bent on large-scale adaptations by way of the photo mural. After all, the sky’s the limit.