Peeling Back the Hidden Pages of History With Hyperspectral Photography

For historians, paper is a cruel mistress. Though dried tree pulp has done more to advance record keeping (and consequently...

For historians, paper is a cruel mistress. Though dried tree pulp has done more to advance record keeping (and consequently our understanding of history) than perhaps any other invention, its fragility and mutability are endlessly frustrating. Things written on it fade. People erase old manuscripts and write over them. Worst of all, it makes excellent kindling. The 20th century saw the discovery of priceless troves of exciting documents across the globe, but these fragile, faded ancient texts have proved notoriously difficult to work with.

Today, though, a renaissance of historical research is under way, thanks to cameras that see far more than our poor benighted eyes reveal to us. A technique known as hyperspectral imaging promises to reveal information that has remained unseen for centuries—text scraped off palimpsests that were reused by monks 1,500 years ago, words concealed under blackened pages, fingerprints that confirm a great man held a particular document when he spoke. Current work in Jerusalem, Egypt and Washington, D.C., will provide new insights into humanity’s cultural origins and settle centuries-old scholarly debates.

The centerpiece of much of this work is a camera system conceived by MegaVision, a digital-imaging developer in Santa Barbara, California. Their specialized systems have long been used for scientific and opthalmologic work, and their Monochrome E6—a 39-megapixel, filterless, computer-controlled camera system—can take photographs at a wide array of discrete bands in the ultraviolet, infrared and visible spectra (optional filters can also be put in front of the lens). Unlike conventional digital cameras, which rely on Bayer color filters to create full-color images, the MegaVision system uses specially calibrated LED lights to take a series of pictures at more than a dozen different wavelengths. This allows the camera’s sensor to detect reflections otherwise invisible to the naked eye. Turns out there’s a lot hiding in the invisible parts of the rainbow.

One of the first major successes in hyperspectral imaging involved analysis of the so-called Archimedes Palimpsest. In 1999, after a 13th-century prayer book was purchased by an anonymous collector, it was deposited at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore to allow scholars to conserve and study the tome’s palimpsests—pages that had been erased and reused. Hyperspectral analysis in 2000 confirmed that while the visible text was from the 13th century, the pages were actually hundreds of years older. It took a team of imaging researchers including William A. Christens-Barry, chief scientist at Equipoise Imaging, several years to illuminate the original contents of what had been erased, but the payoff was significant: two lost treatises by the ancient Greek mathematician and astronomer Archimedes (The Method and Stomachion), as well as a speech by the 4th-century BCE Athenian orator Hyperides and a 3rd-century CE commentary on Aristotle’s Categories.

When the hyperspectral eye was turned on an early draft of the Declaration of Independence written in Thomas Jefferson’s hand, researchers could see that Jefferson had originally written the word “subjects” on one line, which he then scratched out and replaced with the more politically correct “citizens,” exemplifying the egalitarian sensibility of one of the Enlightenment’s greatest minds.

“We can clearly show what text was put down first,” says Fenella France, of the Library of Congress’s Preservation Research and Testing Division. France also notes that extreme-angle raking lights can be used to reveal what is essentially the topography of a document and how it was made. Researchers hope this technique will confirm that the paper this draft of the Declaration of Independence was written on bears—with poetic irony—the official watermark of King George III.

Importantly for conservationists, such results have been obtained without exposing the rare documents to excessive light, which can age and damage historic texts even further. “We believe in adhering to the Hippocratic oath of imaging: Do no harm,” says Ken Boydston, president of MegaVision. Because it shoots multiple images in such narrow bands, the hyperspectral system uses up to 1,000 times less light than a conventional high-resolution imaging system.

This combination of ultra-high-resolution photography with low-light exposure recently prompted the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) to begin using a MegaVision-designed system at the Israel Museum campus in Jerusalem, where some of the Dead Sea Scrolls reside.

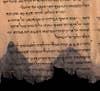

Discovered in a series of caves in the Judean Desert from 1947 to 1956, the scrolls comprise roughly 900 different texts spread across tens of thousands of fragments, ranging in size from that of a dime to half a standard sheet of paper. More than two millennia old, the scrolls are some of the most valuable religious documents ever discovered and include texts that appear in Hebrew and Christian scripture, offering unique insights into the genesis of modern Judaism and Christianity.

Scholars have struggled to piece together and translate the more than 300 different works, but there have always been gaps, including many blackened areas, an artifact of their being recorded on animal skins. Over the centuries, the collagen in the parchment becomes gelatinized, causing certain sections to darken. Eventually they’re rendered illegible.

With the IAA project, hyperspectral images will be able to see past this damage to words that haven’t been seen by human eyes for more than 2,000 years and yield the ultra-high-resolution images researchers crave. According to Pnina Shor, curator and head of the Dead Sea Scrolls projects at the IAA, as many as 57 different images will be created of each fragment. With more than 100,000 fragments in the collection, it will be years before the work is finished. Happily, through a partnership with Google, the fragment images will be made available by the IAA online as they are completed. (Last year, a different set of high-resolution images of some scrolls housed at the Israel Museum’s Shrine of the Book were placed online, also in conjunction with Google.)

Meanwhile, MegaVision’s Boydston has been traveling back and forth to a remote monastery in the Sinai desert. St. Catherine’s Monastery is home to what may be one of the world’s oldest surviving libraries, a cache of ancient manuscripts and documents that has yielded remarkable discoveries. It was there in 1892 that twin sisters from Scotland, Agnes Smith Lewis and Margaret Dunlop Gibson, traveled by camel and braved sand storms and rocky terrain to discover what turned out to be one of the earliest known copies of the Christian Gospels, believed to have been translated around the 2nd century A.D. It was also at St. Catherine’s that the German scholar Constantin von Tischendorf found—and removed—in 1859 what would become known as Codex Sinaiticus. Inscribed around the 4th century, it is recognized as one of the oldest and most complete manuscripts of the Bible ever found.

Armed with one of the MegaVision-based hyperspectral systems, a new team of researchers and scholars from the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library group, a charitable organization working to digitize and preserve rare manuscripts around the world, are now beginning work on a survey of some 120 palimpsests in the St. Catherine’s library. Boydston has been helping the team set up the camera system, which he expects will help the researchers to discover important texts that have eluded previous scholars.

In the meantime, researchers have found additional—and more contemporary—applications for the hyperspectral imaging technology. France notes that conservationists are using the data accumulated from the imaging to assess how well preservation techniques are working, for example. Scientists can now see changes beyond the visible wavelengths that can show early signs of aging or damage and make environmental adjustments before more serious deterioration occurs. Other researchers are interested in the possible use of such systems in the area of forensic analysis.

During one lengthy imaging session at the Library of Congress—it can sometimes take many hours to finish photographing a single document—a raised swirl appeared on the screen. Researchers were examining a copy of the Gettysburg Address, thought by some to be the version Abraham Lincoln used to deliver his 1863 speech. It turned out they were staring at what could possibly be a 149-year-old fingerprint of the 16th president. That discovery led to further research to compare the image with fingerprints on other documents to see if scholars could confirm that it was indeed President Lincoln’s fingerprint (the results of these recent investigations have yet to be published). Researchers also hope to use some of the same techniques to cold-case criminal investigations, but the painstaking work and costly equipment (at $50,000 to $100,000) make the systems prohibitive to apply.

The historic discoveries are just getting started. No one yet knows how much researchers and scholars will find with this new generation of hyperspectral technology. More than a hundred years ago, in the ancient Egyptian city of Oxyrhynchus, archeologists found piles of illegible papyrus. Recently, University of Oxford researchers found that they contained fragments of a lost tragedy by the ancient author Sophocles, of whose plays only seven were known to have survived. New imaging methods have also found portions of a poem by Archilochus that reveal new details about the genesis of the Trojan War. The research at St. Catherine’s could settle long-standing debates over the origins and foundation of some of the world’s major religions.

France notes, however, that uncovering corrections or amendments in historical documents doesn’t necessarily end the discussion: “We tend to open up more questions than we answer,” she says. We say amen to that. AP