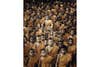

Jimmy Nelson’s Photos of Disappearing Tribes

Endearing or exploitative?

“The motivation is very simple,” says photographer Jimmy Nelson of his ongoing photo series “Before They Pass Away,” which is collected in a lavish photobook from teNeues and as a traveling exhibition.“It is to iconize fragile and remote, disappearing cultures and tribes, and put them on a pedestal. And to look at them in a way that we look at ourselves and we regard ourselves as being important.”

Speaking from his studio in Amsterdam, Nelson was gearing up for a trip to New York City for the opening of a solo exhibit of this work at Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery,which runs through April 18. Like the photographer himself, the show is sure to set off sparks in the art world.

On one hand, Nelson’s portraiture of indigenous people has drawn praise for its artistry, empathy, and scholarly underpinnings from sources including Time Lightbox and The European. His 2013 TED talk got a lot of tongues wagging. American Photo singled out Nelson’s 425-page volume in our 2013 roundup of Photobooks of the Year.

On the other hand, the series has set off a firestorm of controversy. Photographer Timothy Allen criticizes Nelson’s “patronizing and self-aggrandizing narrative” in a collective screed about the work on the website of Survival International, a global organization for tribal peoples’ rights. The group’s director, Stephen Corry, rails against Nelson’s alleged historic inaccuracies and “hubristic baloney” in a post on Truth Out.On Salon, Elissa Washuta, a member of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe, writes that Nelson’s “photographs are aesthetically exquisite…but the artist’s discussions of his work are troubling.” She adds, “He calls himself a ‘collector of truth,’ but how much truth can fit into a work rendered in two dimensions, telling visual stories curated by an outsider?”

Then there are voices in the middle. “What strikes me about Jimmy Nelson is that he is retailing a vision of other cultures that in some symbolic way absolves Westerners of whatever guilt they might feel about their own civilization, and how it has lost touch with what’s real and essential about humanity,” says John Edwin Mason, associate chair of the department of history at the University of Virginia, who regularly writes about issues of race and representation, and blogs about photo history. “It’s the idea of the noble savage that goes back hundreds of years—that somewhere out there are people who are untainted by a corrupting technological civilization. And Nelson has gone out and found them, and he’s staged these elaborate production shots, which in their technical perfection are gorgeous. But what he’s giving people, viewers in an affluent Western audience, is a fantasy. It’s a fantasy that to me says more about the people who are consumers of these images than the people who are the ostensible subjects.”

Jimmy Nelson demurs, “People love to criticize—they always have and they always will,” he says. (One can almost detect a big shrug through the phone line.) “The majority of the people who are criticizing, in my opinion, are not necessarily as well aware of the subjects as I am, or as other people are. In many cases they’ve not been there. And secondly, they’re not actually investigating what I’m trying to do with the imagery, and they are just sort of shooting from the hip, so to speak.”

For Nelson, 47, the documentation of indigenous cultures is a life-long endeavor. “I grew up traveling as a kid. My father was a geologist, and he did a lot of work in the third world. I started taking pictures of this genre when I was 17 until about age 24,” he says. “I was essentially a photojournalist. Then I moved into commercial photography, but I always did this kind of work on the side as a hobby. And I went back to it full-time five years ago.”

His 4×5 images in this project blend the formalism of commercial portraiture with the exploration of documentary work. “What ensues is you end up looking at them in a different way, a glorified way,” Nelson says of his subjects, whom he typically befriends and then photographs in staged sessions, often involving naturally lush surroundings. “It is a manipulated way insofar as they are not standing and waiting for me at a waterfall at five o’clock in the morning at the sunrise. But my argument is, it is no less than what we would give ourselves if we wanted to put ourselves in a positive light.”

The approach is hardly new—nor is the debate. Jimmy Nelson’s own role model, Edward Curtis, was both lauded and criticized for his formal portraits of Native Americans in the latter 19th and early 20th centuries. “Curtis was celebrating Native Americans,” Nelson says. “But it made a lot of people feel uncomfortable, because it put them in the position of respecting them.” He adds that “with Curtis, for all the negativity he received when he was alive—after his death, when the pictures re-emerged, an awful lot of people came to appreciate the iconography that he made. I’ve spent a lot of time in the American West and discussed it with Native Americans, and they salute him. Thanks to him there’s a record of who and what they once were.”

Yet Curtis, like Nelson, depicted his subjects largely removed from their societal woes. “Curtis is such a complicated story,” says Mason. “He showed us his own type of fantasy, which was that Native Americans were dying off, and it was because they were a weaker race that could not compete with this new American civilization that was taking over the land. His pictures are beautiful. But Curtis, in his thinking and in his photography, wanted to leave out disease, famine, warfare—tangible things that had destroyed the Native American population.”

It is the sociopolitical context, or lack thereof, that especially bothers Mason and other critics about both Curtis’ and Nelson’s style of portraiture. “If this way of life is disappearing, then why is it disappearing? And what does it have to do with us, as observers? It turns out that it has a lot to do with us,” Mason says. “But we don’t see that in the images.”

“All I’m trying to do is to highlight these cultures, to say how extraordinarily glorious and special they are for a variety of reasons, and also to re-communicate with them,” he says, noting that his subjects are often grateful when they see the photographic results of his sessions. “I’m revisiting them with the pictures and the books that I’ve made, and starting a dialog about what they already have and how that is, in many ways, a wealth which we have all but lost.”