On the Floor at Sotheby’s Fall 2015 Photography Auction

An inside view of the glamorous and fast-paced scene at a big-name sale

Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico

Georgia O’Keefe

42nd Street, As Viewed From Weehawken

John Lennon and Yoko Ono, The Dakota, New York

Untitled (Chicago Loop)

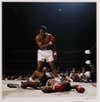

Muhammad Ali vs. Sonny Liston, St. Dominick’s Arena, Lewiston, Maine

Pat Sabatine’s Eighth Birthday Party, PA.

Untitled (Deep South #23)

The music is loud. The crowd is chic. The bar is packed. And the champagne and cocktails flow freely. No, this is not an upscale nightclub. It’s the headquarters of Sotheby’s, the 260-year-old art auction house on New York’s Upper East Side. It’s Monday evening, and the fashionably dressed guests filling the galleries are here to view the lots going under the hammer this week in Sotheby’s fall auction of photographs, the first in a month-long string of major New York City photography auctions that includes sales at Christie’s, Swann, and Phillips.

On plain white walls in a series of large interconnected galleries I come across iconic images. There’s a collection of American landscapes captured by Ansel Adams in prints of stunning depth and clarity (Lot 9, his famous “Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico,” has an estimate of $50,000 to $70,000). Diane Arbus is represented by several images. Lot 165, her famous “National Junior Interstate Dance Champions of 1963” is the one chosen for the cover catalogue (estimate $250,000 to $300,000).

There are unexpected pleasures, too. My favorite is the portrait of Georgia O’Keefe taken in 1956 by Yousuf Karsh (Lot 97, estimate $5,000 to $7,000). Photographed in profile, she sits by a window, the light catching the her features, her right hand clasping a gnarled piece of wood, while above her the skull of a deer with large antlers hangs on the wall like a baldachin over the throne of a queen.

Among the stars of the show is Lot 144, Robert Mapplethorpe’s “Man in Polyester Suit.” In the controversial 1980 photo, the artist’s lover Milton Moore wears a three-piece suit with his penis exposed. Giving it a wall to itself, Sotheby’s has assigned it an estimate price of $250,000 to $350,000.

In the world of photography, coming up with these estimates is no easy business, unless the team can find records of earlier sales of prints that are comparable. After all, photographs may have been printed at a later date than when they were taken. And while earlier prints are generally more valuable, the quality of the print also needs to be taken into account.

Estimates aside, for anyone interested in photography, these auction house viewings are a treat. Here at Sotheby’s, I move slowly, taking in treasures such as Dorothea Lange‘s “San Francisco Waterfront, The General Strike” (Lot 70, estimate $20,000 to $30,000), Irving Penn’s 1948 portrait of Marcel Duchamp (Lot 147, estimate $25,000 to $35,000), and Henri Cartier-Bresson’s 1944 image of Matisse surrounded by birdcages (Lot 145, estimate $6,000 to $9,000). By the end of the evening, I find there are many I’d happily take home.

Prints Under the Hammer

Fast forward to Wednesday. It’s 2pm and I’m at Sotheby’s again, this time in the saleroom. The only sounds are the quiet hum of air-conditioning and the soft murmur of the people settling into the seats in front of the auctioneer’s podium. The hushed atmosphere could hardly be more different from the thumping music and loud chatter of Monday’s reception. But today we’re not here to socialize. We’re here to sell and buy images.

Above the podium hangs a large print of Adam Fuss’s Untitled “Chrysalis” (Lot 212, estimate $10,000 to $15,000), a glorious golden image that adds a splash of color to the otherwise gray, businesslike interior. Fuss, a British photographer known for a camera-less technique that uses objects, light and light-sensitive material, has long been fascinated by the metamorphoses taking place in the natural world. But here, a different kind of metamorphosis is about to occur—the transformation of photographs into money.

Things start to liven up. A short video showing salerooms, artworks, and clinking champagne glasses interrupts the silence with a voiceover that encourages us to “enjoy the auction.” Then the auctioneer arrives. It’s Christopher Mahoney, head of Sotheby’s photographs department, and he’s wearing a canary yellow tie that matches the golden hues of Fuss’s enlarged chrysalis image.

Mahoney has worked at Sotheby’s for 20 years but, as he later tells me, he’s something of a rookie as an auctioneer. Officially licensed for about a year, he’s undergone rigorous training involving extensive mock auctions to work on various techniques, from dealing with the math to learning how to handle unusual situations, such as someone who takes their bid back.

But if he’s a relative newcomer to the podium, Mahoney betrays none of this in his manner. Brisk, professional, and cheerful, he marches through the lots with a broad smile and an air of confidence.

Surprisingly, half the seats in the room are empty. This doesn’t mean there’s no interest in the sale—today, bids come from a variety of sources. There’s the “order bidders,” people who don’t want to attend the auction but authorize the auction house to bid up to a certain amount. Then there’s the phone bids and, more recently, online buyers.

Sotheby’s Photographs Auction, 7 Oct. 2015

This means Mahoney must pay attention not only to the floor but also to the staff taking the phone bids and the screen displaying the online bids. And, he tells me, it all hinges on reading the room. “It’s knowing when things need to go quickly and when they need to go slow,” he explains. “I don’t want to rush anyone especially if it’s going to mean a higher selling price. Body language, facial expressions—you need to take all of it in, so it winds up being a great deal to keep track of.”

As he looks right and left, marshaling bids from all sides, it’s a little like following a tennis match. And some of the rallies can be tense and prolonged. “What’s amusing to me,” he tells me later, “is that there can be just as much deliberation for someone deciding to up their bid by $500 as there is for someone deliberating going to up at a $10,000 increment.”

Along the way, Mahoney keeps everyone informed on where the bids stand, moving things along with phrases like “It’s all against you,” “One more?” and “I’m going to hammer it down.”

Then comes the big moment—the Mapplethorpe lot. It’s the first time in 23 years that a print of this image has appeared at auction (it was last sold in 1992 for $9,900). And it more than meets expectations. After a short bidding exchange, Mahoney brings down the hammer on a bid of $478,000, well above its estimate and the second-highest price for a work by the photographer at auction.

Sotheby’s is pleased. “There’s a handful of photographs that have sold for over $500,000 and we were not too far off,” Mahoney tells me. “That’s a serious price for a photo.” And for Mahoney, this makes the hard work in putting the sale together worthwhile. “There’s nothing quite like the thrill of selling something for a great price,” he says. “It’s a moment of real gratification when everything comes together.”