Notes on Ernest Cole: Hidden Witness to Apartheid

By the age of 25, Ernest Cole had compiled a remarkable and unprecedented visual document of racial injustice under the...

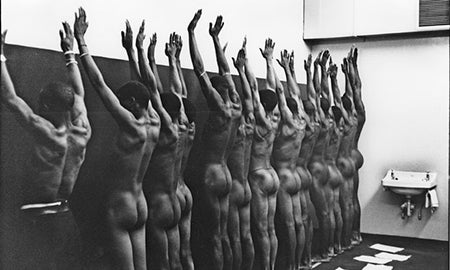

By the age of 25, Ernest Cole had compiled a remarkable and unprecedented visual document of racial injustice under the system of apartheid. Self-taught and inspired by the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson, the black South African photojournalist often worked clandestinely, hiding cameras in lunch boxes, at times even getting himself imprisoned for a closer look at the treatment of his countrymen. Cole smuggled out his photographs from South Africa, and, facing sure exile, saw to the publication of his work in New York with the groundbreaking 1967 monograph House of Bondage. Fred Ritchin, co-director of the Photography & Human Rights Program at NYU, calls it “one of the best books of the 20th century… important both for South Africa and the history of photography.”

A must-see exhibition currently on view at the Grey Art Gallery in New York, presents a wide selection of Cole’s vintage prints, which until recently were believed to have been lost along with all of his negatives. The exhibition reveals the original images, virtually unseen in their uncropped form. On Tuesday night, Ritchin moderated a conversation with Joseph Lelyveld, a foreign correspondent for the New York Times in South Africa—eventually the paper’s executive editor—and author of the 1967 introduction to House of Bondage. Lelyveld, a long time friend of Cole’s who speaks in a classic American newsman’s drawl, recounted his saga—escaping from South Africa, showing up on the doorstep of the Magnum photo agency, publishing the images and finally earning his 15 minutes of fame. That fame dried up rapidly and, along with the racial injustices Cole recognized in the US, left him remarkably disillusioned. Towards the twilight of his life, with a trunk containing all of his negatives lost forever and only a single suitcase of prints floating around somewhere in Sweden, Cole ended up, tragically, sleeping in the subways of New York.

Below is an edited selection of highlights from the talk.

The mid-60s was perhaps the most repressive time under the white racial rule of South Africa. The black nationalist movements, primarily the African National Congress, which now governs the country, and another movement called the Pan-Africanist Congress, which broke away, both were banned in 1960… Because of the repression of the black movements, it was then necessary to bring in all sorts of draconian police powers… The security police were created and they indulged in things like torture and targeted killings and that was very shocking in the ’60s. Now so many people have done it, including ourselves, that you have to be a little guarded in saying how awful it was, because it’s awfulness has been matched many times over in other places. Nevertheless, it was shocking, and the leaders of these movements, including famously, Nelson Mandela, were all put on trial for their lives and went to jail for long periods of time, and the whole [movement] was just sort of put into the deep freeze.

It’s at that point that this young man [Ernest Cole] harbors in himself the ambition to expose the whole thing from the inside through the eyes of black people and tell the story of blacks living in South Africa—an incredibly daring and possibly dangerous undertaking. By … Fall of 1965, he had almost completed the project that became House of Bondage. He was only 25 years old and he was just putting the finishing touches on this work which had been inspired by a collection he’d seen of the photographs of Henri Cartier-Bresson. And that’s when I [Joseph Lelyveld] met him. He showed up in my office with a couple of cameras over his shoulder and introduced himself.

I [had gotten] there [Johannesburg] in May of ’65 and started writing about what fascinated me about South Africa—the whole racial picture of apartheid. Back then the Times editors complained that I was obsessed with race. To which I replied, ‘I’m obsessed with race?’ So I started writing about apartheid as if it was a story. It hadn’t been really a story except in certain flash points. At this time, there were no black movements visible, they were underground and I wrote a story very early on in my stay there—I think we arrived April or May and by July, I wrote a story that really ticked them off [the South African authorities] and I was later told that they had decided at that point to expel me.

Ernest at that point had planned to leave and take his collection of pictures abroad and see to the publication of the book, which he more-or-less knew would cut him off from his country. the book was sure to be banned in South Africa and he was sure to be banned—there was such a thing as banning of people—if he returned or tried to return to South Africa. So he told this amazing story to the Foreign Ministry—or wherever he went to apply for a passport—that he wanted to go to Lourdes on a pilgrimage. It’s true he was a devout Catholic, but he had no intention of going to Lourdes. He wanted to get the pictures out. And so I carried some out for him as I left and he had left less than two weeks later. And we met up in London.

When he got his pictures altogether, he went to Paris, and he went to the Magnum Agency and he just appeared on their doorstep. He had no introduction from an agent or anything of that sort. So the receptionist called down one of the photographers who was working upstairs at that time, a very well-known and extraordinary photographer, Marc Riboud, who had done a book on China around the same time. Ribaud came down and said this was something special and then referred [Cole] back to the office in London, and within a couple of months Random House had optioned the book.

I came back to New York in the fall, probably October, and I agreed to do the introduction and saw Ernest in New York then and he was consulting with the designers. But he wasn’t altogether happy and in the years following became increasingly unhappy with the book. It really was a book designer’s book and they cropped, not brutally, but nevertheless consistently on a number of his best photographs. One of the wonderful things about seeing his photographs that survived [in the exhibition at Grey Art Gallery] is that they are uncropped… They’re wonderful photographs in the old book, which had considerable impact when it was published, tremendous impact, but you’d only need to look at the small differences to realize what a special eye he had. He was not just a propagandist who got into forbidden places, he was actually an exceptional photographer.

From what I could see, I think [House of Bondage] sold well. It was widely reviewed in Britain and the United States; the New York Times Book Review ran a two-page display showing the pictures—it’s not something the Times often does for the review of books. He had what you might say was his 15 minutes of fame. He was taken up, he was lionized, picture editors wanted to meet him, LIFE Magazine gave him an assignment to go to the South, the Ford foundation gave him a grant to complete that assignment, and then… it’s a complex story.

I have a line at the end of my introduction about how he was leaving his story behind and no story would ever matter as much to him in the future as the one he was now telling and that this was a huge sacrifice. That turned out to be far more prescient than I could ever imagine. I saw some of the southern pictures, I don’t think any survive. By then it was 1967; Ernest did not pick up on what was happening in this country. As far as he could see, the southern United States were South Africa and America had his own apartheid. Well of course we had a situation in the South that was miserable from many points of view, but tremendous things had happened there in the few years before he first arrived. The whole civil rights movement, March on Washington, the Civil Rights act, the rolling back of apartheid, the Freedom Rides—and he didn’t get any of it, really. There was a kind of rigidity in his quick read of what was happening that he might have been warned against, but nobody did. And perhaps what that represents was, that he had high expectations of what a life for him could be here, and he discovered that in New York he was a black man, too.

He took images but they didn’t result in an article in LIFE Magazine and you know how things go—within half a year, the picture editors who were eager to meet him and give him assignments when House of Bondage came out weren’t taking his calls, and there was somebody new and exciting who just arrived from some other place, and he was kind of lost. He traveled to Europe a lot, particularly Scandinavia—he had some exhibitions there, quite fortunately because that’s where all these pictures from the gallery come from, basically a suitcase that he left with somebody, a photographer in Sweden. And then he became disoriented. I don’t want to sling around—this man was my friend and I never saw him at a time when he wasn’t very sensitive, very smart, loving in many ways—but he become a little strange.

He was no longer getting grants for his work, he was no longer getting assignments he had no source of income basically, except from the help of friends…I got a message from one of [Cole’s] old mentors from Drum Magazine… and he said that Ernest was homeless, that he was living on the subway… Eventually, I don’t remember how quickly, I heard from [Cole]—it was true. He was in terrible shape.

[I returned to New York from Washington, where I was based at the time, met him and] we went to the last place he had lived. He may have lived off and on with some friends, South African exiles and other people he knew, but this was the last place he had stayed on his own account. It was a hotel on the East 50s called Pickwick Arms… It was a kind of big rooming house, not quite an SRO, whats called a Single Room Occupancy, but it was a hotel for people who were down and out. He had left something, a trunk of all of his important worldly goods in it, including all the negatives from House of Bondage, all the original prints and his correspondence with his mother, back in South Africa and his pictures of his own family. And they said at the time—it seemed to be true—that there are regulations, city ordinances that establish how long a hotel has to keep something that has been left for safe keeping, and then they’re free to auction it off. The man brought down the ledger and showed us the date that they signed it in and the date they signed it out and they said that they were within the law and no one could say where that stuff went. So Ernest lost all of his basic materials, and of course, the negatives were lost forever.

These pictures were more than assertions of injustice at the UN. They were actual images of what life was like. I don’t know what the sales were, but they were widely reprinted in reviews and articles about the book and I think they had considerable impact. There was nothing quite like it because while there were other very good South African photographers including black photographers, they mainly focused on the political movement and ‘the struggle,’ it was called. Ernest…he wanted to talk about the actual lives of people, he wanted to show something far more enduring than people walking with placards, and he succeeded.

Video of this converstion in its entirely will be available through the NYU Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute’s Primary Sources archive.