A New Look at Richard Avedon’s Portraits of the Powerful

Richard Avedon’s original ambition was to dance like Fred Astaire. And from the beginning, his fashion photographs, spectacles of motion...

Richard Avedon’s original ambition was to dance like Fred Astaire. And from the beginning, his fashion photographs, spectacles of motion and sinuosity, embody that desire. There is footage of him from the 1950s or ’60s leaping nimbly into the air to show his models what he wanted.

As photographic subjects, political types usually require a different kind of wrangling, given that the appearance of dignity is crucial for maintaining what Bill Clinton called “viability.”

“They know what to do with their faces,” Avedon once lamented to The Washington Post about politicians. So as he began to take on civic subjects in the ’60s, he was forced to invent a new approach to photographing such public figures, who had spent their lives excising inconvenient facts from their histories the way old men trim sprigs of hair from their ears. These were people who acted more than actors, who had turned themselves into living advertisements for certain points of view. Until Avedon could depict them freshly, he might as well have been working for Revlon or Calvin Klein.

He hit a few bumps early. In 1964 he published a photo-text book called Nothing Personal with novelist James Baldwin (they met as classmates at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx). A collector’s item now, the book was savaged in its day. It’s not hard to see why. What Avedon intended as a “photographic polemic against racism” ended up being a crankier and more American version of Edward Steichen’s influential book The Family of Man, its unimpeachable sentiments worn on its sleeve like little valentine hearts. In a particularly pointed spread, Avedon juxtaposes a band of sieg-heiling American Nazis commanded by George Lincoln Rockwell against a naked, hairy Allen Ginsberg. One is led to understand that anti-Semitism is not a good thing. Baldwin’s accompanying essay is an angry, heartbroken sermon, next to which Avedon’s photographs seem devalued, reduced to illustrations and made to serve a pious liberal master rather than the more mysterious dictates of appearance. He borrowed the grainy style of Robert Frank’s The Americans in photographing patients in a Louisiana mental hospital, as if such graininess signified the ugly reality the nation would rather not face. Woe is America; we are become a giant loony bin.

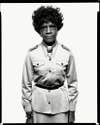

In the late ’60s, having overcome the chastening reception of Nothing Personal, Avedon embarked on a new political project under the working title Hard Times. Using for the first time a Deardorff 8-by-10-inch view camera, he began photographing an array of subjects who were either part of or opposed to what was then known as “the Movement”: Black Panthers, Young Lords, American soldiers, Vietnamese napalm victims, U.S. government officials in charge of directing the war, student demonstrators, radical lawyers, gay poets. Rather than crouching behind the lens, as he had done for decades with his favored Rolleiflex, he now stood beside the camera, engaging his sitters face to face.

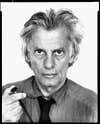

He photographed them in what became his signature fashion: in a bluntly frontal manner, against a white paper backdrop, sheared away from any setting or prop, framed only by the black edges of the negative. The subjects stand isolated in a kind of existential police line-up from which there is no escape, no appeal and—most disturbingly for the politically inclined—none of the solace afforded by a community of like-minded souls.

Avedon intended this, says Marvin Israel, the designer who worked with him. “[Avedon] will attest to the fact that the white paper…is a way to separate the people from their universe, their life.”

The photographer himself said that this visual treatment “makes people symbolic of themselves.”

Consider the three-panel, 10-foot-tall mural of the Chicago Seven, a group of activists on trial for inciting a riot at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Reproduced above, the scale of a magazine can never do justice to the imposing size of the original. To see it in person is to stand in the presence of a conversation just interrupted. But the billboard stature of the defendants buys them no movie-star glamour—Avedon applies the enlargement of image so beloved by fashion photography and Hollywood to a bunch of schlubs. The wrinkles on everyone’s pants look so fresh they could have been made that very morning of November 5, 1969. Here is Tom Hayden, braided peasant belt, denim workshirt, boots, as anti-mythic a man who ever won the heart of Jane Fonda. He confessed later that as his picture was taken he was worried about selling out and being commodified. His anxiety shows in his refusal to strike a pose. Rennie Davis has an obvious stain on his pants. Abbie Hoffman’s eyes are closed. A thickly bearded Lee Weiner peers either wryly or smugly at the camera, seemingly certain that history—if not Judge Julius Hoffman—will absolve him.

Unlike the swooning movement of his fashion photographs, Avedon’s political murals evoke a stillness in which you can hear the ticking of a clock. The defendants stare at us from their historic moment as we stare back at them—like two tribes taking the measure of each other from across a watering hole. You can see them summoning the attitude by which they will represent themselves to posterity. Avedon’s murals are not just pictures of history but images of people thinking about their place in history.

In 1971 Avedon made another classic mural, this time of a group that the Chicago Seven surely would have considered antagonists, the so-called Mission Council. These 11 American military and government officials ran the Vietnam War from Saigon, and were then implementing the policy of Vietnamization—putting the war in the hands of the South Vietnamese. The photo is an extraordinary depiction of American power, though one wonders how these men must have felt placing themselves in the control of a photographer who, though hardly a firebrand, had hosted “peace parties” back at his studio in New York.

They don’t seem too worried. A few appear bemused. Others look eager to get back to work. General Creighton W. Abrams Jr. alone wears fatigues. The rest of the men are in suits, confident, hands folded in front or slipped into pockets, jackets draped. One fellow’s tie displays a psychedelic print. These men have secrets, a notion Avedon reinforces by doubling a few of the figures into two-sidedness. They don’t appear to envision the possibility of helicopters landing on the embassy roof just four years later to rescue the remaining Americans from Vietnam.

The writer Renata Adler, Avedon’s friend and collaborator, wrote that the photographer “had virtually no interest in politics. He was enormously interested, however, in power—especially the role that power plays in photography itself.” By the mid-’70s, Avedon felt no qualms exercising the power he had gained as a famous photographer. The deck was stacked in Avedon’s favor; so great was his reputation that he could get almost anyone to sit for him. And because he required magazines to allow him the final choice of image, he always got the last word in the eternal contest between subject and artist over whose idea of appearance would rule.

On October 21, 1976, as the country neared its bicentennial election, Avedon commanded an entire issue of Rolling Stone for a portfolio called The Family—69 portraits of 73 selected members of the American power structure, as picked by Avedon and Adler. Rolling Stone’s art director at the time, Roger Black, credited Avedon with having the “best bedside manner” of any photographer he’d ever worked with, an essential attribute that proved useful for inducing the powerful to stare into his camera. Great statesmen, responsible for the fates of countries, came to Avedon’s studio as supplicants. Henry Kissinger begged the photographer to “be kind to me,” a favor he might better have asked of a Cambodian orphan or the ghost of Salvador Allende.

There is nothing particularly partisan in the portraits contained in The Family. Instead, their detail turns viewers into modern-day phrenologists, scrutinizing faces and bodies as if they were secret maps of character. Do Kissinger’s pudgy cheeks, for instance, represent his smugness, an appetite for power so great that he swallowed a subcontinent or two?

Is that an enigmatic smile on the face of Rose Mary Woods, Richard Nixon’s secretary, she of the infamous 18-and-a-half-minute gap, here packed into a tight-fitting patterned blouse and skirt? (Avedon rejected pictures from her initial photo session, in which she looked worn and secretarial, a four-leaf clover pinning her Peter Pan collar.) In one of history’s ravishing ironies, the sort often intuited by great artists, next to Woods stands a blank-faced W. Mark Felt, the former associate director of the FBI later revealed to be Woodward and Bernstein’s Watergate informant, “Deep Throat.”

The sober picture of Jimmy Carter included in the portfolio belies its origins. The presidential candidate had the misfortune of being photographed toward the end of the Rolling Stone project, by which point Avedon found himself exasperated by politicians. He goaded Carter into extending a handshake toward the camera, a gesture Avedon knew would make the candidate look like a pharmaceutical salesman or a used car dealer out to sell a clunker. The images, which are kept in the archives of the Richard Avedon Foundation, would have followed Carter for the rest of his days like hecklers at a campaign rally. But at the last minute, Avedon softened, encouraging Carter in a serious pose that bespoke intelligence and ambition. Nearly all of the subjects here signal their power with a similar kind of studied reticence.

Black says Avedon intended The Family as a visual novel. “You’d pore over a face like a page of prose. Imagine when Dickens was doing serializations in the 19th century, or when Hunter S. Thompson was doing Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas in 1971—that’s very much what Avedon was doing.”

Avedon was still photographing political subjects when in September 2004, while on assignment for The New Yorker in San Antonio, he suffered a cerebral hemorrhage. He died a short time later. He had been working on a project called Democracy, roaming the country snapping an array of politically engaged citizens—including Iraq War veterans, convention delegates, political operatives. Experimental to the end, he was using more color for this series, continuing to seek novel ways to embody the civic circus, with some portraits even bordering on the grotesque. Only weeks before Avedon died, he photographed Republican strategist Karl Rove, who recoiled when he saw his portrait, saying it “makes me look like a complete idiot.” He accused Avedon of being “an elitist snob who deliberately set me up.” Outtakes from the photo session show that Rove left Avedon with few alternatives.

As a man who made his living manipulating image, Rove may have felt the sting of others doing unto him as he had done unto so many. But there is no denying the stark, nowhere-to-hide mercilessness of Avedon’s political portraiture. Roger Black says that when The Family was published, many readers regarded its portraits as “vicious, mean-spirited and cruel.” Their reaction is understandable, but not quite right. Avedon’s political photography ventures beyond the journalistic record of an era to investigate the forbidding questions concealed in a face. “I often feel that people come to me to be photographed as they would go to a doctor or a fortune teller—to find out how they are,” Avedon said. One ransacks these portraits for clues, ranging over every wattle, every wrinkle, every wild hair as parts of a new and mysterious landscape. Power is not aggrandized in such pictures. Instead, at their best, Avedon’s photographs strip away everything but the singular fact of a particular life, frozen forever in time, like mastodons found in a Siberian glacier.

The director Mike Nichols, a friend of Avedon’s, said that his pictures “never close the issue.” They are more complicated than the reductive politics of any given moment. Instead, for Avedon, every face was its own story, a party of exactly one, richer, subtler and more mysterious than any ideology or movement that might attempt to subsume it.

Thanks to The Richard Avedon Foundation (avedonfoundation.org) for their generous support in the development of this article. -Ed.