Lillian Bassman’s Abstract, Re-Imagined Fashion Photography

A fresh look at fashion imagery that was ahead of its time

In the early 1970s, after decades as a successful fashion photographer, Lillian Bassman got fed up. Disillusioned by the direction that commercial fashion imagery was headed, she stopped taking assignments and even destroyed most of her negatives and prints—which now seems like a bizarre act of a mad artist.

“It’s not that weird when you think about it in the context of the time,” says Ali Price, assistant director at the Edwynn Houk Gallery, which is staging an exhibition, Lillian Bassman, of her painterly images that opens May 12. “She had been a commercial photographer who was very active in the ’40s and ’50s. But in the ’70s, it was a a very quiet art market for photography. There wasn’t much of an outlet. Most photographers, not even she, would find that their prints would ever be in a gallery, because photography was still a stepchild in the art world.”

Meanwhile, editors and art directors wanted new looks. “Bassman saw how styles were changing in fashion and in how things were being photographed, and that was not what she was interested in,” Price says. “So it was, ‘Out with the old, in with the new—I want to focus on other things.’” She turned her attention to personal art photography.

Fortunately, an assistant had stashed a cache of negatives of Bassman’s brilliant early work in her Upper East Side carriage house. “They were found in the ’90s by Martin Harrison, who was a fashion curator and historian and a friend of hers,” Price says. “He suggested to her that she look at them again. She did, and she found that she could make her own choices in how they were printed and how they looked—she could go back and reinterpret many of them.”

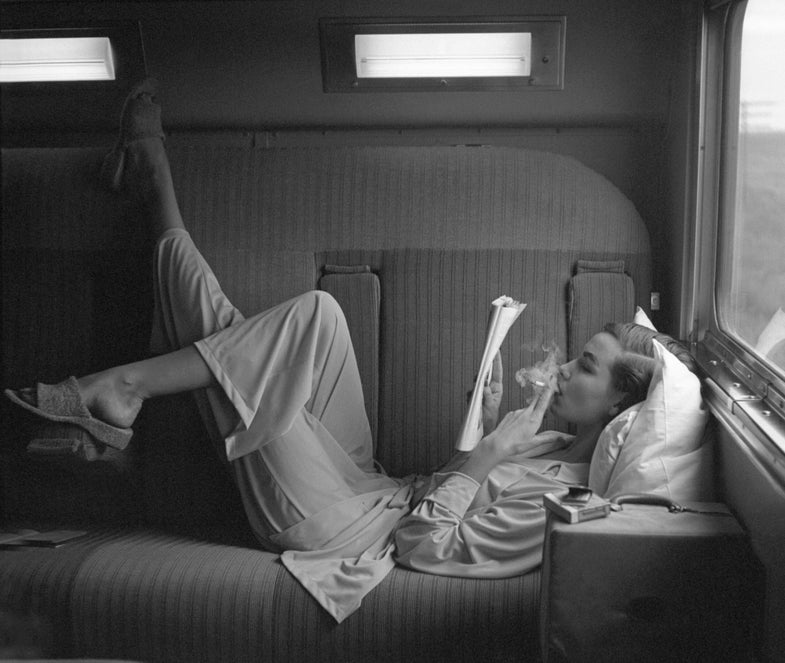

The experimental results, first achieved in the darkroom and later using a computer, transformed Bassman’s lyrical renderings of the human form into abstract studies in light, shapes and mood. “I think it’s easy to allow yourself to be lost in them, because it’s all about feeling,” Price says. “Could you be that person in that picture? The images look timeless.”

Her aesthetic sensibility often ran counter to ephemeral concerns. “For Lillian Bassman, who emerged in the high-performance arena of design and photography in the New York of the 1940s, energy, tension, and creativity never seemed far apart,” Martin Harrison wrote in a 1995 piece for Graphis magazine. He went on to recount a dispute that Bassman had with Carmel Snow, her editor at Harper’s Bazaar: “You are not here to make art,” Snow implored the young photographer. “You are here to show the buttons and the bows.”

While Bassman did fulfill that brief, she increasingly did so in an artful way. “I tried to make my pictures soft and flowing,” she told Harrison. “I was never interested in the straight print, and I was trying out soft-focus effects by printing through tissue or gauze and vignetting with ferricyanide bleach.”

Having started out as an art assistant to famed art director Alexey Brodovitch at the Bazaar, Bassman relied on her graphic background when she moved behind the camera. “Her training as an illustrator and in graphic design is apparent in her work,” Price says. “When she was one of the art directors at Junior Bazaar (a younger version of Harper’s Bazaar), she was giving assignments to people like Richard Avedon and Robert Frank. But nobody else had her style. You could say it was avant-garde, and it was original and not contrived.”

In later years, Bassman’s new work and reinterpretations of classic images did find an art market, with exhibitions around the world; the Edwynn Houk Gallery acquired her estate after her death at age 94 in 2012. The images in this show range from 11×14-inch vintage prints to more recent platinum prints of up to 30×40 inches.

“Up to the end, she was always active and working on something,” Price says. “But I don’t know that she was all that concerned about her legacy. She was doing it for herself, because she was a creative person.”

Lillian Bassman will be on view at Edwynn Houk Gallery through July 8.

Lilian Bassman