The Most Famous Pictures That You’ve Never Seen

Contact sheets from some of history’s most iconic images are on view at the Fahey/Klein gallery in LA

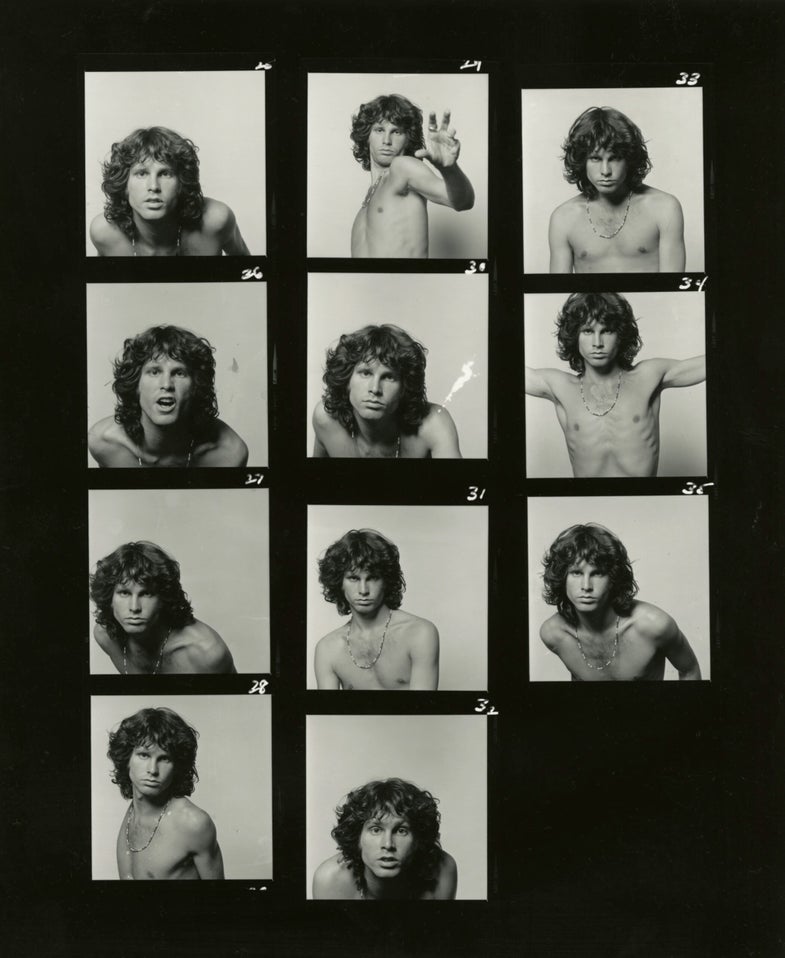

Some photographs are as iconic as the people they capture. It’s hard, for instance, to not think of Jim Morrison without picturing him gaunt, shirtless and stoic as Joel Brodsky immortalized him in 1967 for his “American Poet” shot, or to even imagine Lee Harvey Oswald not forever frozen in pain thanks to Jack Ruby’s bullet catching him mid-perp walk in Robert Jackson’s Pulitzer-winning news footage of that fateful day in Dallas.

But what about the photos taken during those same shoots that aren’t as famous? Los Angeles’ Fahey/Klein Gallery is celebrating both with its latest exhibit, Contact. Running through January 28, the showcase displays contact sheets for some of the most memorable shoots in fashion, pop culture, and history next to large-scale renderings of the final results. Aside from Brodsky and Jackson’s works, there are glimpses into Herb Ritts’ OCD-like attention to detail as he obsesses over slight differences in photos of the back of a model in a Versace dress for his “El Mirage” project in 1990 and also into how controlling Marilyn Monroe was of her own image after a photo shoot with Lawrence Schiller (she used a red marker to veto all but two photographs—one of which didn’t even show her face).

“People have done contact sheet shows before, but they were oversized contact sheets so you could see the whole shoot,” Fahey/Klein Gallery gallery owner David Fahey says. “What I like about this show is we try to select iconic photographs and then we try to find the contact sheet related to it, so you’re looking at the little teeny image that this massive, oversized print came from. You can see the evolution of the shoot and the final big print. I just like the idea of the little thing and the big thing.”

He says the choice in photographs was an “exhibition that grew out of our ability to locate things quickly,” as contact sheets tend to be owned by different people or corporations and his gallery staff usually only has weeks to prepare for each showcase. A fan of photojournalism, Fahey has placed the Oswald photograph near Stephen Somerstein’s photos of Martin Luther King, Jr. in Selma, Alabama, telling the stories behind two of the most important photographs of America in the 1960s. (He adds that it was just a coincidence that Phil Stern’s photographs of Frank Sinatra and an out-of-focus John F. Kennedy on the latter’s presidential inauguration night are across the room from Oswald.)

“When we sequence the show, it’s really based on formal issues: how it looks on the wall and how the shapes work,” Fahey says. “And, secondarily, we try to combine thematic things and images from the same period that represent the same kind of idea.”

Fahey says he doesn’t mind that the exhibit is “a mixed group” of genres of celebrity. He cites one of the items—William Claxton’s capturing of fashion model Peggy Moffitt wearing Rudi Gernreich’s infamous Monokini—as a “classic,” but knows that not everyone may think so. He also likes the “subtle differences” in Julian Wasser’s photographs of Joan Didion, which are also on display, adding that “with all of the people in those images, it’s so much to with what they want to project; that unguarded moment that is acceptable but is also authentic.”

Selma to Montgomery March

“I like the fact that pictures become famous for different reasons; they connect with people and there’s a reason for it,” Fahey says. “It’s kind of like a golden moment that people can relate to at different levels. They may not like the photographer’s work, but [it’s] that single picture that connects. So many people, so many photographers, if they’re lucky make a great single picture and then they work their whole career trying to do other pictures.”