Mexico’s Morbid Landscapes

For Mexican photographer Fernando Brito, views of death are an occupational hazard. As photo editor of the newspaper El Debate...

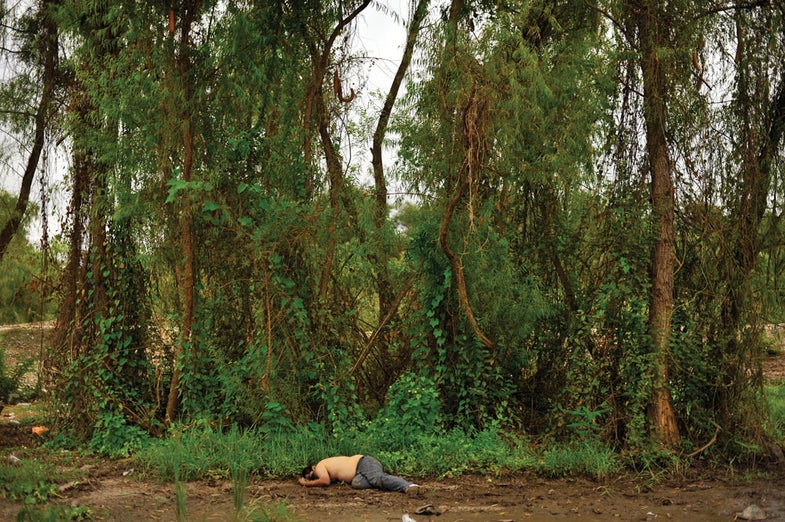

Homicidio en La Higuerita

For Mexican photographer Fernando Brito, views of death are an occupational hazard. As photo editor of the newspaper El Debate in Culiacán, Sinaloa, he regularly sees and prints sensational scenes of murderous violence in the region, much of it sparked by turf wars between rival drug cartels and their battles with the Mexican government. According to U.S. Open Borders, an online aggregator of news and information about the U.S.-Mexico border, Culiacán’s murder rate exceeds one per day and the state of Sinaloa’s is even higher.

A few years ago Brito began a personal project shooting alternate views of corpses he encountered in his work. “The idea was to make people aware of the problem. I think too often we are asleep, isolated, social orphans,” Brito says. “It makes me sad to see these forgotten people, day in and day out. They go from real humans to statistics and old news overnight.”

In his series Your Steps Were Lost in the Landscape, Brito depicts the bucolic Mexican countryside punctuated by bodies; the victims are shown from a respectful distance, isolated amid an eerie tranquility. “These are not sensationalist, tabloid-like photographs,” Brito says, “and there is not a single living person in them.” In the photo community, the project has touched a nerve. Brito’s numerous awards include third prize in General News at World Press Photo 2011 and the Descubrimientos PHE Award at PHoto-España 2011, where he was overall winner of a global competition. The series has been shown in venues including the Russian Tea Room Gallery in Paris and Musée de l’Elysée in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Brito himself seems more interested in visual storytelling than receiving accolades. “I’m not an artist,” he says during a private press tour of his show in Madrid. “I’m a citizen with a problem.” Yet isn’t this a story he’s conveying in an artful way? “I am trying to report what is happening,” he replies. “My job allows me to work on a project to denounce this problem, using the mask or disguise of art to be able to reach the galleries.”

He concedes that the work is not for the squeamish. “I have been told about the emotions caused by my photographs,” he says. “Once, I printed the images and someone who worked in the place where I did it recognized his brother in one of the photos. He said that he was OK with me being the one making the picture, because he could see the respect I feel for the dead and their families.”

Brito says he’s created this project alongside but separate from his newspaper reportage. “I’ve never been alone with a corpse,” he’s explained to Vice magazine. “I was never the first on the scene. There are certain people that we call, like the police and funeral services. There are also usually other reporters there from other newspapers. We rely on each other so that we’re never alone. When I’m through with my tour around the body, getting the photos I need for the paper, I stand in a place where I will get the shot that I want and wait for everyone to move out of the frame. Sometimes I take a ton of photos; sometimes I take only one.”

While the crime scenes vary, one common feature in the photographs is a rural landscape. “Some of these people were killed right there,” Brito says, “and in some cases, the bodies were wrapped, moved, and thrown away.” While much of the violence can be traced to drug wars, Brito says it’s simplistic to generalize. “Many of these victims are innocent people caught in the crossfire,” he says.

How long does he plan to continue the series? “It will go on indefinitely,” he says, adding that there’s no end in sight to the violence. “I just want to bring to light issues that some people try to ignore,” Brito says, “in order to grant the dead a little more time in this world, so that they won’t be forgotten.”

CLOSE-UP: Fernando Brito

Lives In: Culiacán, Sinaloa, Mexico

Studied At: Universidad de Occidente Culiacán (marketing)

Awards Include: Descubrimientos PHE Award at PHotoEspaña 2011; Third Prize, General News, World Press Photo 2011; Mexican Expo

Foto Periodismo, 2010 and 2011

Photo Training: On the job, as photo editor of El Debate since 2004. “The moment when I started working at the newspaper, it changed my professional career,” Brito says. “I went to workshops and conferences, and received a good visual training through work.”

In the Bag: Nikon D800; Nikon SB-900 AF Speedlight; lenses include 50mm f/1.4 AF-S Nikkor, 24mm f/1.4G ED AF-S Nikkor wide-angle, and 80–200mm f/2.8D ED AF Zoom-Nikkor telephoto.