Interview: Thomas Hoepker on 60 Years of Photojournalism

Thomas Hoepker has spent the last 60 years working as a photojournalist, is a former Magnum president and has been...

Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali

New York City

New York City

New York City

Ex-GDR

East Germany

Thomas Hoepker has spent the last 60 years working as a photojournalist, is a former Magnum president and has been a member of foundation since 1989. This October he will release a comprehensive retrospective of his career: Wanderlust: 60 Years of Images. Here, he looks back on his career and speaks with Marc Erwin Babej about the changes in the industry and what it is like to be a Magnum member.

Let’s start at the beginning: How did you discover photography?

In 1950, I was 14 at the time, my grandfather gave me a 9×12 camera. It used glass plates and fascinated me. It was primitive, even for the time, but also very traditional. When I finished school, I bought a modern 35mm camera. My father wanted me to get a “real job,” so I began studying art history, but I already knew that what I really wanted was to become a photographer.

Before I knew it, I got an offer to work for a Munich newspaper as a photographer. I had barely started there when the paper shut down. Next, I moved to Hamburg to work for the magazine Kristall, and was sent around the world on assignments. One day, my editor asked my writer partner Rolf Winter and me if we would like to go on assignment to the United States. Of course we did! We spent three months traveling across the US, all expenses paid. It was a fantastic opportunity for us.

Your story begins to remind me of Robert Frank, who traveled across the US 1955-57.

Robert Frank’s book, The Americans, was a guiding star for me. It showed me how one can approach a large theme. Just before I left on the assignment, I bought the book.

Shortly after, you started working for Stern, correct?

In 1964, I received a call from the editor of Stern, Henri Nannen, who made me an offer I couldn’t refuse. And I didn’t.

If you had to choose one project you did for Stern that really defined your work, which one would it be?

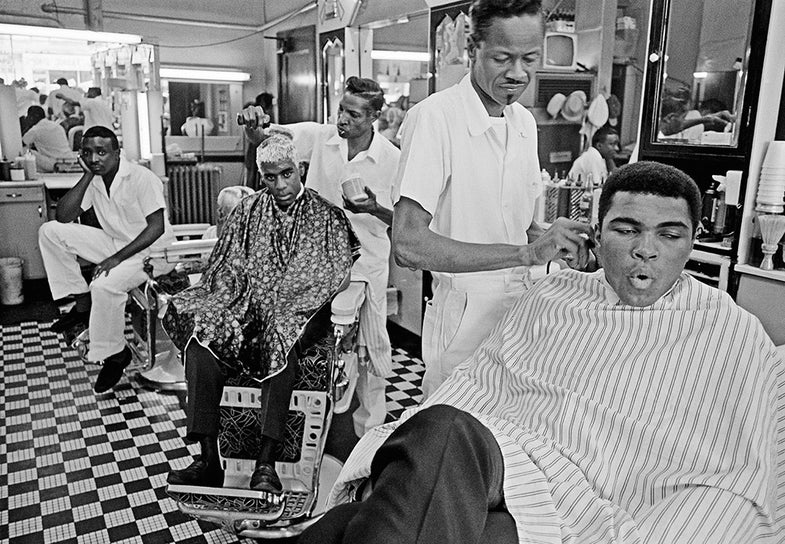

Muhammad Ali. I owe him a great deal: he made it possible for me to shoot him not only as a boxer, but also—no, I should say above all—as a human being. I didn’t know much about boxing at all, and wasn’t particularly interested in it. I shot Ali only once during a fight.

I got to know Ali at a very interesting moment in his life: he had just converted to Islam and was almost incarcerated because he didn’t want to join the military and go to Vietnam. He was a complex person: a bigmouth on the one hand, and on the other hand a disciplined and hard-working athlete. He was an incredibly funny and spontaneous man, who knew how to market himself.

On my first visit to Ali, I arrived with Stern reporter Eva Windmöller. As a black Muslim, he didn’t want to talk with white women or be seen with them. So we agreed that we would just be observing him. It was the best thing that could have happened to us: being bystanders to his life allowed us to get a front seat on the life of a thrilling, fascinating character. One moment he could be falling asleep in the car; the next he would play-box with kids on the street.

Muhammad Ali

When did you last see him?

About two years ago, in London. Unfortunately, his Parkinson Syndrome has progressed a great deal, and he didn’t recognize me.

You can look back on a career of more than 60 years. How has photojournalism changed in that time?

In a word: fundamentally. At Stern, we had 15-20 staff photographers, who were paid generous salaries. Today, this is unimaginable. Last year, Volker Hinz, the last staff photographer at Stern, retired. Today, magazines buy photos from the Internet and use freelance photographers once in a while.

Looking back, working conditions back in the day were a dream. We got great salaries, flew business class and were given the time to do the job right. There were even occasions when the photo editor would say: ‘the images aren’t quite right yet. Travel back there and get some more.’

And today?

Editorial departments of the big magazines only rarely have budget for photo productions. On the other hand, they have access to images through photo agencies. This change in the market hasn’t been all bad for photographers: as freelancers, they have more opportunity to develop their own style and vision, rather than operate under the vision of an editorial department.

Conventional wisdom has it that the rise of TV marked the beginning of the decline of photojournalism.

TV has been operating in parallel to printed images for decades. True, people spend a lot more time in front of the TV screen than with magazines. True also that TV is immediate in a way that printed images couldn’t be. But for us photographers, this spelled not just a threat, but also opportunity: we have more opportunity to present our own point of view and style.

You were the first full member of Magnum from Germany, and from 2003-2007 president of Magnum. How did you get there?

In the late 1960s, I received a letter from Elliott Erwitt, who had always been my idol. He invited me to join Magnum. But I had just started at Stern, so I declined. But when my contract as a foreign correspondent at Stern expired in 1989, I resigned and went to Magnum.

And you’re an active member of Magnum to this day. Magnum has a mythical status – how does one become a member?

Magnum was an exclusive club from the very beginning, and remains so to this day. One can’t just join, but has to be appointed – following a long and difficult procedure. Every year, we receive more than a hundred credible applications. By the time we’re done reviewing them, there are two or three left. These become nominees. After two or three years, they can become associates. A few years later, they are either brought on as full members – or they have to resign. We have excellent photographers and have only made few mistakes over the years.

Magnum is a collective… comprised of individualists. How does that work?

It’s not easy, because we have to deal with big egos of big photographers. But it’s worth it. It makes for interesting friends and colleagues – sometimes also enemies and competitors.

Magnum was founded in 1947. In the past 65 years, photojournalism has changed fundamentally. How is the Magnum of today different from the Magnum of the 60s, or even 80s?

At heart, Magnum has remained the same: we’re reporters who describe reality. But many of us have also moved in a more artistic direction. With assignments becoming a rarity, photographers create series and then offer them to media. Today, I earn my income with books, and with prints that are sold on the art market.

Like a fine art photographer. Do you see yourself as an artist or a journalist?

In the beginning, I was reluctant, because I wanted to be a journalist, not an artist. Magnum has influenced my views over the years. Magnum photographers are both journalists and artists. A truly strong photojournalistic image is a reproduction of reality, nothing about it can be faked. But today, there’s more room for interpretation of reality by the photographer: style, eye and aesthetic all matter. Even at Magnum, everyone has to make his own decision how far he wants to go in presenting reality through his own eyes.