Interview: Julian Sander’s Family Business

Julian Sander was born into the art business. The owner of Feroz Gallery in Bonn, Germany, Sander is also the...

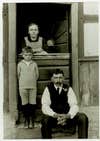

Julian Sander was born into the art business. The owner of Feroz Gallery in Bonn, Germany, Sander is also the great-grandson of the German documentary photographer, August Sander, who was best known for capturing images of German life in the early twentieth century. This year Feroz Gallery is curating an eight-part cycle of August Sander’s work. The gallery is currently showing the fourth installment, People of the Twentieth Century: “The Woman.”

You’ve had an unusual beginning as a gallery owner because you were born into the art business: Your great-grandfather, August Sander, is widely considered one of the most accomplished and influential photographers in German history.

August Sander was, effectively, the first conceptual artist. He understood photography as a documentarian medium. But from the outset, he stepped outside of pure documentation. With People of the Twentieth Century, he created a multi-faceted body of work that amounted to a typology of German culture in the first decades of the twentieth century. He conceived of it this way from the very beginning, and worked on it for more than 60 years, until his death in 1964.

Sander’s first book, Antlitz der Zeit, though later forbidden by the Nazis, made its way to the United States and influenced, among others, Walker Evans Irving Penn and Richard Avedon. In Germany, photographers such as Bernd and Hilla Becher. Sander influenced their basic understanding of photography because he had the rare combination of being conceptually strong, and at the same time a masterful creator of images. It has influenced people as far as modern-day China’s Jiang Jian, who worked with the same ideas and methods as Sander in China in the ’70s and ’80s—without ever having heard of August Sander.

How has his artistic success translated into financial success of his work?

The work has continued to increase in price over decades. When the art photography market was still nascent in the 1970s, the price for a vintage print was about $20,000 in today’s dollars. In the Sotheby’s auction in New York this April, his image of the painter Heinrich Hörler, sold for $170,000. The highest price ever achieved at auction was £486,000, for his 1926 image Working Students. The highest price ever is for an exceedingly rare print of his 1928 image Pastry Chef, which is on the market for €1 million.

Those are lofty prices, particularly for photography. How do you account for this increase in value of his work?

The biggest factor is the rule of supply and demand. The vintage photography market has continued to reduce in quantity because museums have been consistently buying up work. At the same time, the contemporary photography market is realizing the value of Sander’s work because they have found a dead end in the technological development of photography.

For the longest time, people assumed that technological mastery was required to create great photographs. But technology alone doesn’t account for better pictures. Technology in itself is not meaningful, and Sander’s work is all about meaning. That kind of insight doesn’t come with the right camera—it takes a certain person. And Sander’s work is among the earliest to crystallize this difference, in a way that is relevant today as it was back then, because he captured a certain timeless essence of his subjects.

You’re in a rare position as a businessman: in charge of a multi-generation family business, and your most important business partner is a great-grandfather who passed away before you were born.

Yes, that’s true. We’ve been doing this in this family for four generations. I’m the third generation art dealer, fourth generation photographer, and second-generation gallery owner. I come with a loaded deck. But the story of our business also includes experiences one wouldn’t wish on others – such as not having enough money for food when the work wasn’t selling. Or showing work of Sander’s that I believe in, knowing well that sometimes it’s harder to sell.

Do his landscapes fall into that category?

Yes. They’re harder to sell because they’re not as strongly associated with him, and therefore are deemed less valuable. That said, they’re considerably more rare, and they have a very interesting back-story. He learned to love landscapes and nature through his grandmother, and found in them an escape from the horrible events of Nazi Germany.

His book had been banned by the Nazis and he was ostracized by society as a result. This even though, even after his banning, there were Nazis who asked to be photographed by him. He wasn’t forbidden to work, but went into a kind of “inner exile” during the Third Reich. His oldest son, Erich, was imprisoned on political grounds and died in captivity because he was refused medical care for appendicitis.

As a business, and as an artistic venture, how do you see the future of your gallery, Feroz?

I have effectively reinvigorated the market for August Sander by placing it in a contemporary context, starting with the Sao Paulo Biennale two years ago. This year, Feroz is doing an eight-part August Sander cycle. We are currently opening Part 4: The Woman. Considering the historical background and expertise in contemporary art and technology that I have, I believe we will continue to succeed.

How does technology come into play for a photo gallery?

The way we consume visual information has changed dramatically in recent years. On the one level, it has forced a layer of abstraction. People are looking more for patterns in pictures than just at pictures themselves. The sheer quantity of pictures is another factor: Take a web page where you see grids of images, such as Tumblr or Google images. In choosing one image, you become its discoverer, in a sense. That process is very different from a specifically curated process where an expert chose one picture and designs the space around it, the way Joseph Duveen did. Nowadays, people don’t respond when there isn’t a certain loudness and density of images.

Has August Sander influenced the way you do business?

In our family, we focused not so much about the importance of Sander as an artist, but on his humanity and understanding people. The arts were the language he chose to speak with, if you will, the brush he chose to paint in. That core understanding has been with us ever since. My father has shown us how to deal with the arts, how to embrace them. This also extends to how we do business, the level of humanity we bring to it. My parents didn’t want us to focus on money, or fame, but rather on the artistic merit and the content of an image.