Interview: Ed Templeton’s Wayward Cognitions

Ed Templeton has spent the last twenty years documenting youth culture from the streets. A former professional skateboarder, Ed’s interest...

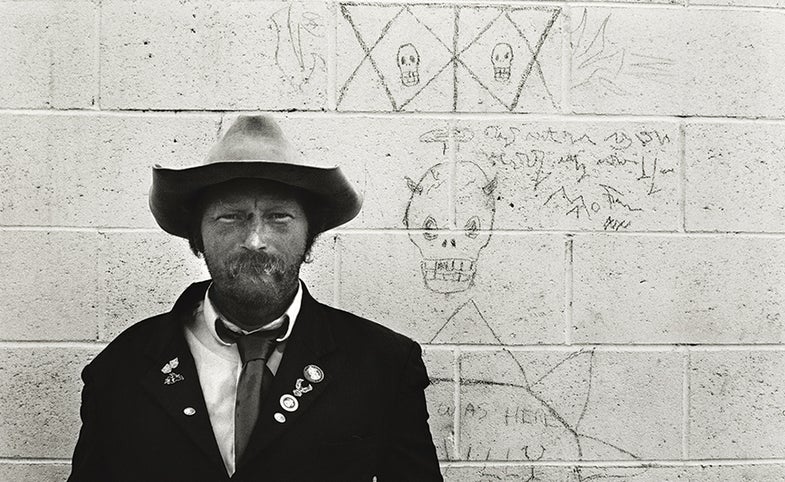

Ed Templeton has spent the last twenty years documenting youth culture from the streets. A former professional skateboarder, Ed’s interest in photography and art was driven, in part, by the founding of his company Toy Machine. This year, Templeton released Wayward Cognitions (Um Yeah Arts.) Here, Templeton talks about diving into his immense archives for the new book and the things that catch his eye on his daily photo missions.

Books like Teenage Kissers, Teenage Smokers and The Second Pass were all organized around really tight themes, Wayward Cognitions isn’t. How did this change the editing process?

Everyone thinks it was easier, but in some ways it made it harder. For Teenage Smokers, there were only a few criteria: young people and a smoker so it was pretty easy to find the photos from my archive. For this one, the possibilities were really kind of endless. I had to put a lot of thinking into what I was going to choose. That was kind of how Wayward Cognitions as a name came. I was thinking about what happens to all the photos you shoot on a daily basis, I just walk around shooting sort of willy nilly, I have ideas in my head, but in general I’m just kind of shooting. The name Wayward Cognitions means stray thoughts. That is what these photos are, kind of stray thoughts. The stuff that you just do and then it ends up sitting in your archive and just disappearing. I wanted to try and find weird stuff that wouldn’t really fit into other series.

You were looking through 20 years of archives, what was the process like and how did you get started?

My archive is only partially digitized, for years I just did proofs and put them in the books. I’ve finally been scanning the proof sheets and separating each individual image from the proof and titling it. I’m doing it religiously now as I go, but going backward is really hard. To some extent I had to go and look through physically each book and the proof sheets, which becomes sort of daunting.

It kind of started when I found the first image in the book. I didn’t even know what I shot when I shot that. I saw these kids sitting on this ledge. When I looked at that photo again, I realized the girl has her head in her hands and the two boys are laughing at her. It started saying a lot more to me. You shoot and once you get the photo back it kind of has a different meaning, I put the word childhood on that photo because for a lot of people that is childhood, getting made fun of. That kind of set the tone. I didn’t necessarily want the perfect sort of decisive moment. I think a lot of it is in-between moments.

What do you think makes for good “in-between” moments?

It’s funny, it’s different than the proverbial decisive moment where something is happening and you capture that one thing perfectly. A lot of my photos are, I’m walking and I see someone who has some interesting clothes or looks cool. I just kind of look at them, and as I’m walking by, I shoot a photo. I do a quick composition, I sort of guesstimate the distance I’ll be and I’ll shoot. In that way it is almost like I’m just a bird flying by, I just got a snapshot of whatever is happening in that moment and the only thing that spurned me to shoot it is that person.

They are mid-conversation, or sipping a drink, or whatever. Some of those, not all of those—sometimes you get a blink or a really weird mid conversation face—but other times you get a cool, really weird snapshot of life. I really like that when you walk by someone and they are on their smoke break and they are just thinking, sitting there in that frozen moment, where they are not staring at anything in particular.

It sounds like you end up doing a lot of people watching when you shoot: where are some of your favorite places to do that?

On a daily basis my wife and I go down to the pier in Huntington Beach where I live. A lot of my work is doing the skateboard graphics or painting in my studio, inside stuff and sitting, so I kind of feel like I need to get out of the house. We live so close to the beach that it is nice to take a daily break and take a walk—it becomes a photo mission, really. We just go out with our cameras, get a drink, and walk the pier.

Then when we travel ,we are kind of just in the streets in general. When we go to Europe we always tack on a few days in London. Oxford Street in London is a super busy shopping street, there are a million people walking around. It is like shooting fish in a barrel there. Every time we are in London, we do this long walk from Central London all the way across the river to the Tate Gallery. In a way it is like, oh lets walk to the Tate to look at the art, but on the way there we have this two hour walk and it forces us to be out shooting.

Walking is the key. We like to just go to cities and not take the subways or taxis. We’ll kind of put these ludicrously long walks in front of us just to get out there and get our feet on the ground.

Have you had any bad confrontations with strangers while shooting in the streets?

Not really. I think there is a science to it, an etiquette that has been built over the years that I’ve figured out. A smile disarms a lot of things, I’ve been caught and you just kind of smile. Luckily I haven’t shot anyone who saw me and just resorted straight to violence. A lot of the times I don’t get seen because of my walking style. I’m also in the super bright sun all the time in Huntington. I can be walking full speed and not even stop and just shoot and it is going to stop the motion and be perfect because it is such bright and unrelenting sun. I think Martin Parr says never look back. I’ll shoot and, yeah they might have seen me, but you just keep walking and you never look back.

It sounds like you are doing a lot of composition in your head. Is that correct?

For sure, if you were watching me from above you would see my path take a weird erratic turn. I see somebody and then I have to make a decision real quick: Is it a full body shot? Do I have to get close? A lot of my focusing is guesstimation. I see someone so I focus my camera accordingly and then I put my camera in that position to make my focusing correct. I don’t shoot from the hip or anything. I look through and compose in that split second, I’m walking by and I kind of slap the camera up to my eye make that millisecond composition and then shoot. Sometimes you fail of course, but I’m more and more surprised by how good I am at getting everything in there, getting what I wanted in there and getting the exposure right.

You printed every image in Wayward Cognitions in the darkroom before scanning it in and working on the final layout. Why do you like to do everything yourself?

There has gotta be a control freak aspect to it. One of the reasons, starting maybe from skateboarding, is I just ended up having to do everything myself. I started a skateboard company and I had no one to help me with the advertising, laying out the ads, so I was forced to learn to do that. I was also doing the skateboard graphics. All of this art stuff I do, I was basically self taught, I just learned things off of friends. I got this self reliant streak—I can build it all myself. I have it all here. I have my darkroom and I have a nice big scanner and I know how to clean up the photos so its like who better?

Of course I complain about it the whole time, because cleaning photos and scanning is just … doom. It is just soul killing hours in front of the computer. I never think of myself as a control freak, but because I can do it all, I just want to do it all.

With the film aspect, as a photobook fan, I geek out on that kind of stuff and get stoked when I see old prints. I want to do it traditional and hand print everything and then scan it and do it in an old school way. I think that there are a few people who will appreciate it. I’m not delusional, I think 99 percent of people in the world won’t even care how it is made, but there are a few that might.

Do you think photobooks are the ideal way for people to experience your work?

Photography works really well in a book form because you have that sort of captive audience that sits down and flips at their own pace through a sequence of photos, and you can really take the person who decides to sit down and look at your photos on a certain ride. A book is one thing, but when I do shows, some of them have these giant clouds of photos, these clusters. In that way your eye is seeing multiple photos at the same time. You look at one but there is one literally touching it next to it, and maybe it is mixed with some drawings and paintings. The exhibition can bring out a different thing, it is not so much about the one story where you sequence through. I wouldn’t say there is a best way, just two different ways.

Do you have any favorite images from the book?

There are a ton. One part about this was using photos that I wouldn’t normally use that kind of fit within the framework of this book. There is a photo of a businessman shadow where you can see his arm—things like that. The fun photo stuff that you shoot, you just do it, and you get it back and it’s like, ‘oh, this is really cool, but what is it going to fit in?’ That’s what this book was for. It was like this is exactly the book it fits in, it is kind of a photographer’s photobook.