Instant Expert: Bernd and Hilla Becher

There are few photographers with work as obsessively cohesive as that of Bernd and Hilla Becher. The German husband and...

There are few photographers with work as obsessively cohesive as that of Bernd and Hilla Becher. The German husband and wife duo spent their entire career photographing nothing but industrial structures in Europe and North America. For this reason, a Becher photograph is almost immediately recognizable–the industrial subject matter, the muted black & white tones, the focus on form, and the absence of any people or activity. They don’t have “periods;” they have one massive project spanning nearly five decades of photography together (and, let’s not forget, marriage—doubly impressive).

And yet, in spite of such a rigorously limited scope (or perhaps because of it), the Bechers’ work is among the most influential in contemporary photography today, especially in Europe. So what is it about these outwardly simple photographs that draws such an enthusiastic response?

The Grid

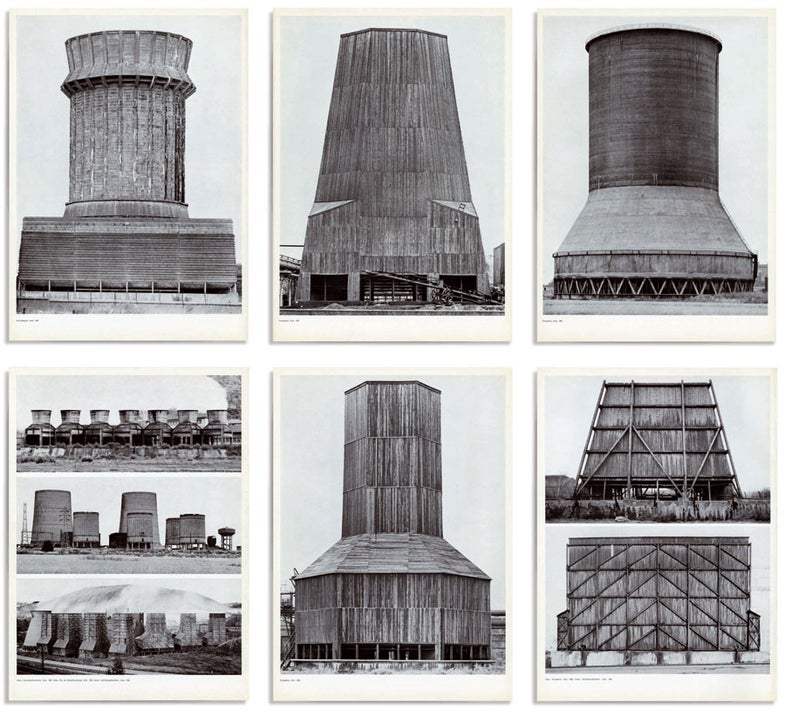

The Bechers began working together in 1959 (they were married in 1961), and continued until Bernd’s death in 2007. Their constant goal was to document the architectural forms of industry—gas tanks, grain silos, water towers, blast furnaces, storage barns—mostly in Europe but also in the United States. A group of shots of one specific type of structure would be displayed together, either in a monograph or hung in a grid, in order to create a formal comparison or “typology.” It is this emphasis on form that is most crucial in the Bechers’ work.

The workers inside the factories are not directly acknowledged in the photos, which never betray any hint of labor, activity or motion—human or otherwise. They are taken under overcast skies, to avoid shadows, and from the same exact perspective. Nothing distracts from the pure form of the structures, which are elevated to the level of sculpture. The Bechers have made direct reference to this connection by titling an early show “Anonymous Sculptures,” and when their work won an award at the Venice Biennale in 1991, it was in the sculpture category.

“Anonymous Sculptures”

This interplay between medium and terminology is probably why the Bechers have sometimes been aligned with conceptual art. And in a sense, this is correct: it is the “concept” that drives their work—the concept that there are families of industrial forms, that utilitarian architecture can be appreciated for its aesthetics, and that these buildings can be re-framed and re-presented as sculptures. And yet the beauty depicted in these structures is undeniable, especially when grouped together for comparison; in the grid, your eye hones in on the subtle differences from structure to structure–a reminder that they all sprung from a conscious (and creative) human design.

But this “conceptual” categorization is often a slippery and unstable business, particularly when dealing with photography. And the Bechers don’t seem to care much what labels are placed on them. As Hilla once said, “The question ‘is this a work of art or not?’ is not very interesting for us.”

In addition to form, the other major element that must be discussed when considering the Bechers’ work is memory, or preservation. The Bechers were fascinated by the speed at which technology evolves, leaving old innovations in the dust, often to be destroyed. They worked actively to preserve the memory of these structures by photographing them, often scheduling their projects around demolition dates, and on more than one occasion photographing one end of a factory while it was being torn down on the other. But it is a memory entirely devoid of sentimentality or nostalgia, for their consistently straightforward style prevents the injection of emotion into any of the images. As viewers, we have no idea if the factory in front of us still stands today, or was leveled years ago.

Founding the “Düsseldorf School”

The Bechers have also left their mark on the history of twentieth century photography as professors and mentors. Both taught for years at their shared Alma mater, the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, and have been very influential to an entire generation of photographers commonly referred to as the “Düsseldorf school.” This loose grouping includes Thomas Struth and Andreas Gursky—two of the biggest names in contemporary photography today.

Tanks

The work produced by the Bechers’ students in the Düsseldorf school, often taking the form of large, color prints, is much more varied in scope than the Bechers’ own work—how could it possibly not be? But their influence is explicit. Struth’s series Paradise, for instance, aims for a similar but broader “typology” of form, with densely wooded jungles and forests as the “object” being categorized. And in his well-known photographs of museum-goers looking at major works of art, Struth even more directly refers to photography’s complicated relationship with the world of fine art, and its overlap with other artistic mediums.

For Gursky, whose monstrously large color prints have fetched some of the biggest price tags in contemporary photography over the last two decades, the focus on form over all else remains. Even when his photographs contain thousands of people—frantic traders on the floor of the Chicago Board of Trade, in one well-known image—the emphasis is placed on the forms and patterns that emerge from these masses of humanity when viewed from a distance in exquisite detail.

The Bechers’ work, characterized as it is by a remarkable combination of modesty and ambition—so narrow in focus, so wide in scope—is perhaps a surprising ancestor to such a rich and varied photographic output. But the power of their work, the stark elegance of the images and the fascinating effect of repetition and variation in their series, demonstrates their ability to create work that is specifically photographic while gesturing beyond the medium – to sculpture, to music – pointing up the vastness, the flexibility of what photography can do and be. And that is inspiring.

_This is the first installment of Instant Expert, our series on the masters of photography, giving beginners the basic facts and placing them in historical and critical context. If you’re familiar with the artist here, hopefully you’ve taken this time to think about them anew. And if you didn’t know them, well—now you do. _

Emma Hamilton is pursuing her Ph. D. in Comparative Literature at NYU. She has written for Words Without Borders_ and_ BUST_ magazine._