How James Nares Creates His Moving Portraits

The artist speaks with American Photo about the illusion of stillness in his newest body of work

“It’s like watching sheep in a field — did they move?” James Nares says with a laugh, when I visit him in his Chelsea studio to talk about his series, PORTRAITS. He’s referring to his recent exhibition at Paul Kasmin Gallery where at first glance, it looks like a photography show, down to the flat white mat board that frames eleven portraits of his friends and family. But if you turn away for a second, you might look back to notice that the gaze of one of his subjects has followed you, or that another is actually moving, out of synch with real time. And then you’ll see that the images are actually HD monitors and all of the portraits are actually videos playing in extreme slow motion.

The London-born artist, who has lived in New York City since 1974, has always been interested in time — from his film, Pendulum (1976) in which he hung a long swinging object in the middle of a Tribeca street, to his time-based, singular-movement brushstroke paintings he made while suspended by a harness, to his video, STREETS (2011), a slow-motion capture of New York City — but for this project, he’s working with a hybrid art form that might be more akin to still photography and painting than to the realm of video in which it technically resides.

Using the new Fastec Imaging TS5-Q camera, which boasts a frame rate of up to 359 fps, he focused his lens on friends like director Jim Jarmusch, writers Hilton Als and Amy Taubin, and his daughters — taking anywhere from a five to 15-second moment and slowing it down to a range of 11 to 35 minutes — all for the purpose of “pulling back and looking at one person for a long time.” The resulting moving images are haunting spectacles of human expression and a nod to classic studio portrait photography.

I caught up with him to find out what it all means, and how his interest in photography fueled this series.

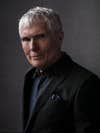

Jim, 2015

You played in a band with Jim Jarmusch, who’s one of your subjects in PORTRAITS, and I’m wondering how music plays into the way you make work.

I think primarily in terms of rhythm; I was always a rhythmist. I think rhythm and time play a role in everything I do. I think the color of the music appears in the gestures, which are very dancelike. There’s a strong connection in my paintings. The whole body is dancing but it’s curtailed in the hand and the wrist. I make these enormous brushes and I make the paintings in one movement. There’s a kind of unity to the painting.

Sasha, 2015

You say that your paintings are representative of photography in a lot of ways and that the amount the time it takes you to make a painting mimics the making of a photograph. I’m curious what you meant by that.

Photography and painting have had a dueling relationship since the dawn of photography really—and it’s taken many forms. Artists have used and referenced photography in so many ways but it’s usually in the visual aspect. The way I feel I reference photography is in the temporal aspect. The paintings are made in a matter of seconds; what you see is the main event, so to speak. The brushstrokes are quite quick to make. So you experience the painting in kind of the same instant it was made.

So you’re stopping time?

I’m arresting a small fraction of time, in the same way that a photographer does.

It makes a monument of this tiny slice of time.

Yes. And the speed thing too—the paintings are done with a speed that you’re unable to really experience as it’s being made. You can only see it afterwards. Which is the same as in high-speed [photography], where you take things the eye can’t see because it happens too fast and make them visible.

Zarina, 2015

What drew you to the Fastec camera, and how did this camera capture movement in a different way than your film, STREET?

The Fastec is less sophisticated than the Phantom Flex [high-speed camera] used for STREET. But it is still a sophisticated camera, and I love it. I had bought one of their earlier cameras, the Troubleshooter. I loved that camera. I shot a lot of things with it. What astonished me about it was that it was designed with scientific or industrial purposes in mind. It was one of the earlier high-speed video cameras. But it made the most beautiful painterly image. The image had a kind of weave to it which made it look like it was on the canvas or something, And the color was very unique. I saw that Fastec had come out with these new cameras and they looked beautiful, for what looked like a high-speed point-and-shoot camera. It also has a very unique image quality—it’s painterly too. So it was perfect to use for these portraits. They exist somewhere between painting and still photography and moving images.

At first I wanted to do portraits where I circled the sitter. And I found my camera movement interfered with what was going on, and there was plenty going on without me having to do that. So I dropped the handheld thing and put my camera on a tripod and let my subjects be the center of attention.

In the press release for this exhibit, you were quoted as saying, “a still photograph is a lie. People are not merely a single moment in time.” What did you mean by that?

I guess what I meant was that a still photograph doesn’t show you what happened just before or just after. A still photograph is always a moment taken out of context. And the context always changes things. You may read the photograph as one thing, but actually it’s something completely different, as all photographers know. It’s just your choice of moment.

A painter looks at his or her subject for a long time. And when you look for a long time you see more, just by definition of looking at someone for a long time. You see the physical aspect, but then you also see the depth in a person. Photographers do the same thing; it’s not so different. What I was thinking of is how a painter condenses a larger slice of time into one image. The painted portrait is a kind of condensation of time and thought and observation and imagination.

Walter, 2016

And the totality of a person’s expression.

Yes. A still photographer does that with lighting, choice of camera, film and exposure. The tools are different, but it’s exactly the same. I was thinking that there’s a pleasure in looking at something for a long time and maybe my portraits would give people a feeling of what it feels like to just look at someone for a long time. You can get a sense of what a painter sees. You can see all these minute fluctuations in facial expression; all the micro movements of the face and hands.

There’s a lot of vulnerability in the videos.

Which I like to see, or at least I don’t like to hide if it’s there. I realized this camera is a powerful weapon. It’s quite easy to make people look ridiculous and I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to capture the beauty in people; the beauty in their vulnerability. Because that’s what connects you to other people; to see a person transform from strength to vulnerability to laughter.

Did you learn anything about your subjects in reference to your relationship with them?

It seemed to make sense to me if I were going to do these portraits to start with my friends and people I knew. There’s an element of trust there which you need for this. I think I learned something about everybody. I can’t say that I suddenly learned some sort of deep truth. But I was surprised that some of the people looked very different [in slow motion] than how I see them when I think about them in my mind.

Sara, 2015

Were you intentionally referencing Dutch master painters in your portraits?

Not intentionally. The lighting is all natural light. I had different colored backdrops. All people have certain colors about them. And the floor was painted black. One I didn’t show is one of my wife, “Elizabeth,” and she was wearing an earring that became the subject; it resembled the [Johannes Vermeer’s] “Girl with a Pearl Earring.” But, “Jahanara” ended up looking like a Caravaggio because she had a very stark sfumato and beautifully mottled dark and light tones. And “Sasha” looks like the Mona Lisa; I loved it because she can look really tough. Kids that age know how to present themselves to a camera. And that was surprising to me to realize how easy it was for the younger people to look into the camera. I had asked people to look into the lens — they don’t call them the windows to the soul for nothing. I wanted my sitters to feel trusting enough of me to look into the camera.

Sara, 2015

Maybe that’s where it differs from cinema and becomes more like a still photograph.

With Jim I was surprised at first he didn’t want to look into the camera. And at first I thought it was because I drug him out of bed early in the morning, and he had had a late night editing [his most recent film]. But he’s the one who looks into the camera the least. And I think it’s because of his background in cinema. And because of that he creates an imagined world outside of the frame. I can’t help but imagine him as a captain at sea with a storm brewing on the horizon. The other thing is with a person like Jim, who is used to being hounded by cameras, I think you hone the ability to avoid people’s eyes. His eyes at times approach the lens, but then they sort of brush right past it. I kind of find that nice. I wanted people to look into the camera as much as they could but this wasn’t a screen test.

There’s the famous Andy Warhol [screen tests] where the girl is trying so hard to look into the camera without blinking and she’s just crying into the camera. And I didn’t want that. I wanted to draw people out rather than scare them.

Glenn, 2015

What did the editing process look like for this project?

I played with the speed. I sped parts up and slowed other parts down. I would just choose one clip, not edit clips together. There was something about the singularity of each one that began to appeal to me more and more. I wanted it to be one moment or one event in time. I realized you see different things at different speeds. I learned you might miss something at a very slow speed that you would see if it were faster. I tried to get each portrait to the speed where the most interesting thing was seen. I was able to shoot for 15 or 20 minutes [with the solid state drive on the camera]. The files are between 20 and 30 gigs.

Douglas, 2015

You make all this work about time. How do you explain your personal relationship to time?

I think it has a lot to do with the musical thing—timing, rhythm, time as a historical thing. STREET I thought of as making a kind of instant historical document. Pendulum is a film of an enormous cylindrical object hanging on a wire in the street in Tribeca, where I lived years ago. When I made it, I wasn’t thinking about this at all; I was thinking more about weight and gravity and time in a different way. But when I look at it now, it looks like this giant clock ticking away the time. And it’s all happening in this city that has disappeared. Downtown was like a ghost town. The meaning of the film has changed just by virtue of its aging, which was nice to see. Art accrues meaning as it gets older, or loses it.

How does PORTRAITS fit into the conversation? I realized they are a kind of hybrid object. People have trouble pigeonholing a hybrid. I think that’s an interesting thing to observe about what I’ve made. By mixing up categories it makes trouble of a sort. I’m not a trickster by nature. I don’t go for that kind of mystery, but I ended up with it.

Amy, 2015