In Gay Gotham, A Community Speaks for Itself

A group exhibition that explores the roots of the LGBTQ art scene

Critics, curators and art lovers have a tendency to place individual artists on pedestals—to see one person as the apex of a certain style or movement. But artists do not work in vacuums, and are not, as we so often like to envision them, solitary figures who create work in isolation. There are communities behind most (if not all) major movements in art, and Gay Gotham, on display at the Museum of the City of New York, reveals how crucial those networks were to the lineage and evolution of LGBTQ art in New York City.

“I think people will be surprised by the extent of these networks, and how important they were to people and their careers,” says Gay Gotham co-curator Stephen Vider. “By putting this art into a historic context, you begin to see the social scene more clearly, and really see New York City as an incubator.”

Spanning half a century, the exhibition establishes connections between artists and art forms that would otherwise go unnoticed, and links major moments in queer history to geographic locations in New York City. It’s a truly holistic view of what we now call the gay rights movement, but more importantly, provides a visual and physical history of a marginalized community through the actors, filmmakers, painters, musicians, writers and photographers who lived and thrived among cultural adversity and political oppression.

Donald Albrecht, MCNY’s Curator of Architecture and Design emphasized the show’s multi-faceted approach to exploring the gay subculture of the city via networks, as opposed to individual artists. “The show really has to be viewed as a synthesis between LGBTQ contributions to life in New York City in the 20th century as well as the gay geography of New York and how these communities and networks were formed.”

While Gay Gotham does showcase the work of 10 specific artists, split across two levels and separated by two different timelines, both curators noted that their intention was to feature artists who weren’t just well known among the mainstream, but who also crossed genres and generations, influencing the culture and community that in turn inspired them. Peter Hujar’s iconic portraits of his friends and lovers, and Robert Mapplethorpe‘s erotic and confrontational images feel comfortably at home in Gay Gotham, but the show truly shines in the work of less familiar artists, like George Platt Lynes, Alice O’Malley and Chantal Regnault.

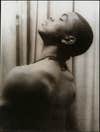

Lynes, a professional fashion photographer in the crushingly conservative 1940s and ’50s, used his camera to create beautiful portraits of his friends and colleagues, with subtle and, in the case of his male nudes, not-so-subtle clues about his own desires and his subject’s hidden homosexual identities. On the surface, much of Lynes’s work is a reflection of the kind of stately, upright masculinity that was expected of men in the mid 20th century, but the way he staged his scenes and posed his subjects, limbs entangled and bodies intertwined, alludes to a bending of rigid gender lines and arbitrary moral codes that would later inspire Mapplethorpe, who Albrecht said was a big fan of Lynes’s photographic figure studies.

By the 1960s, the networks that had fostered Lynes and colleagues like Cecil Beaton and Carl Van Vechten had morphed into vibrant creative clusters in New York City. It was a time of radical activism, and the queer community responded with art that demanded progress and forward movement, while at the same time looking back in an attempt to define itself. “There was more activism happening, partly in response to state oppression,” Vider says, “but the ’70s is also a time of legacy building where the sense of a ‘gay identity’ becomes more solidified.”

In oppressed and marginalized communities, lineage is hard to come by. Evidence, artistic or otherwise, is often hidden or destroyed by a dominant culture that sees alternate histories as insignificant and unworthy. But in the later decades of the 20th century, LGBTQ artists took it upon themselves to document the communities that nurtured them. From anonymous photos of men cruising Times Square in the 1960s to Chantal Regnault’s shots from the Voguing and Ballroom scene in New York and New Jersey and O’Malley’s photojournalistic images of women at legendary lesbian bar the Clit Club, the art and photography in Gay Gotham shows a movement establishing itself, refusing to be defined by anyone other than those directly contributing to its livelihood.

Gay Gotham is on view at the Museum of the City of New York through Feb. 26, 2017.