How Crime Photography Changed the Way We Understand Crime

"No one who made these photos was thinking about making art"

John Dillinger’s Feet, Chicago Morgue, 1934

“If photographs are supposed to freeze time, these crystallize what is already frozen, the aftermath of violence, like a voice-print of a scream.Their subjects are constantly in the process of moving toward obliteration. It is death upon death, from animal to document.” – Luc Sante in Evidence

Crime photography is as disturbing as it is fascinating—toe tags dangling from the feet of a famous gangster, a human head dropped on a cobblestone street, mug shots of notorious criminals and crime scenes filled with mystery and dread. This is what crime looks like through a camera lens: dark, dangerous and eerily captivating.

There are few things that the invention of photography hasn’t impacted in drastic ways, and Crime Stories, on display at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through July 31, examines the medium’s effect on how we look at crime, how crimes are solved and investigated, and our seemingly endless fascination with it. Author Luc Sante, who sifted through the last remnants of the New York Police Department’s archive of crime scene photography for his book Evidence, says that images of crime and the criminally inclined can take on a sense of dread and foreboding for a combination of reasons, both intentional, subliminal and incidental.

“It’s hugely complicated, because that sense of mystery isn’t produced by anyone except the viewer,” he says. “With the NYPD photos, they were working with these wide angle lenses that could capture every detail of a room, and were using the old magnesium flash powder, which produced this incredibly bright light and created a black shadow around the periphery of the image, but it’s only us, with our removed point of view, who can take an attitude to find them strange or beautiful or weird. No one who made these photos was thinking about making art.”

Summary Chart of Physical Traits for the Study or the “Portrait Parlé,” ca. 1909

Crime Stories roots its investigation in the work of French scientist Alphonse Bertillon, who used photographs to document the facial features of convicts and who formalized the practice of forensic photography. His albums are full of charts and measurements illustrated with blunt, informative images and his portraits of dangerous French anarchists look like criminal carte-de-visites. In recognizing photography’s power to capture detailed information, Bertillon revolutionized law enforcement, but the images he gathered were never intended for publication or distribution. That task was left to the media.

Human Head Cake Box Murder, ca. 1940

Photography was an unquestionable game-changer for the press, who capitalized on the relative immediacy of early news photography and the inherent drama of the criminal act. This is where the exhibition makes its obligatory turn toward Weegee, whose tenacious self promotion and deadpan take on death placed him at the top of the early tabloid game. But when placed alongside the equally impressive work of anonymous news wire photographers—including one of the show’s most surprising and interesting images of John Dillinger’s bare, toe-tagged feet, sticking out from under a white sheet—it’s clear that Weegee was one among many, drawn to the scene of the crime by morbid curiosity and an impending deadline.

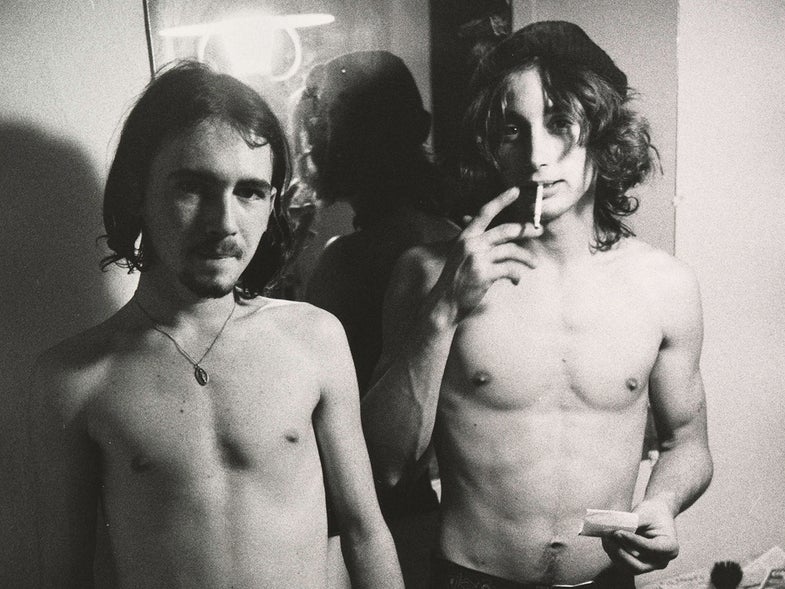

Armed Robbers, Oklahoma City, 1975

The major difference between press photos and police photo, Sante says, is in their intentions, and the question of intent looms large over Crime Stories. But the power of influence is what truly ties the show together. From artless evidentiary images and mugshots to sensationalized murder mysteries, photographers from Walker Evans to Richard Avedon latched on to the powerful aesthetics of crime photography, using it to create their own exceptional work.

“Avedon was a very interesting photographer, and was obviously fascinated by the mugshot. You can see it in the way he would isolate extraneous details,” Sante says, referring to the photographer’s portrait of Dick Hickock, which is included in the exhibition. In photographing the murderer made famous in Truman Capote’s novel In Cold Blood, Avedon gives his subject the full studio treatment, with perfect lighting and in the medium format square frame favored by fashion and advertising photographers. But in capturing Hickock’s blank expression and shooting his subject dead-on, Avedon created a mugshot with the beautiful formality of a portrait.

Electrocution of Ruth Snyder, Sing Sing Prison, Ossining, New York, 1928

Evans preferred to keep a comfortable distance from his subjects, so Crime Stories fittingly illustrates his fascination with crime photography by including pieces from his personal scrapbooks, including the January 13, 1928 edition of the New York Daily News, with the shocking and iconic photo of Ruth Snyder’s execution by electric chair on the cover. Taken by a reporter with a secret camera strapped to his leg, it’s easy to see how Evans may have been inspired to use a similar method a decade later in his famous hidden camera photos of unsuspecting subway riders.

Bank Robber Aiming at Security Camera, Cleveland, Ohio, March 8, 1975

In Evidence, Sante suggests that we are drawn to images of death and decay because they are images of ourselves that we will never see. While crime photography might not have sparked our odd obsession with the afterlife, it certainly satisfied it in a way nothing else had before, exposing the sinister and unsavory in grisly detail. The fact that it continues to fascinate us is only a testament to photography’s unique power to freeze time, even if it’s the moment when we cease to exist.

Automobile Murder Scene, ca. 1935

Murder of Madame Veuve Bol, Projection on a Vertical Plane, 1904

Patricia (Patty) Hearst During Hibernia Bank Robbery, San Francisco, 1974

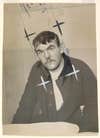

Marius Bourotte, 1929