How the internet changed social movements

Social media platforms have created a constant flow of information. How do we harness that power and not be overwhelmed?

A new show at the International Center of Photography, Perpetual Revolution: The Image and Social Change, takes an in-depth look at how our relationship with social media has fueled the social movements of our day. Presented in six parts, the exhibition looks at the environment and climate change, the refugee crisis, gender fluidity, the Black Lives Matter movement, the growing influence of ISIS, and the rise of the “alt-right”—a political movement that combines aspects of racism, white nationalism, and populism—and its influence on the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Curated by a team of eight, Perpetual Revolution includes the work of more than 100 artists and takes a wide view at what makes something a photograph—videos, Instagram accounts, mixed media pieces, and even embedded tweets make up the work in this fascinating and timely exhibition.

“The seismic shifts within the photography and visual culture landscape since Cornell Capa founded ICP are undeniable,” ICP Curator Carol Squires said regarding the new exhibition. “With our deep roots in photojournalism and documentary photography, it is important to show how the network has impacted these genres and immensely broadened the conversation.”

Perpetual Revolution opens with a section on climate change. A clip from James Balog’s 2012 documentary Chasing Ice, that depicts the largest recorded calving iceberg in Greenland, greets viewers as they enter the space. The large chunks of ice deteriorating into the ocean is simultaneously beautiful and horrifying. Balog’s photography dramatizes the data describing the effect of rising sea levels on the world’s coastal communities.

This first gallery also tackles the way in which people are fighting back against environmental degradation. Video footage from Standing Rock Reservation presents visual evidence of officials releasing dogs on protestors occupying the land and attempting to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline. It’s a heavy group of work, although Mel Chin’s short film provides a bit of a bright spot. This piece was filmed in Paris during the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference (the day after the terrorist attacks on the city) and features an Inuit man who drives a sled led by a team of coiffed French poodles; he has arrived in the city to urge the people of the world to work together towards new solutions in regards to climate change.

The exhibition’s second section, The Flood: Refugees and Representation, examines the European refugee crisis through the lens of documentary photographers and the refugees themselves. Pulling from the museum’s archives, the show incorporates the historic work of photographers who captured the refugee crisis following the World Wars, including Ruth Gruber, Robert Capa, and David ‘Chim’ Seymour, alongside the recent Pulitzer Prize-winning work of photographers such as Sergey Ponomarev and Daniel Etter.

I found a video piece featuring Syrian refugee Thair Orfahli, who used his smartphone to document—via tweets, WhatsApp messages, and videos—his terrifying journey across the Mediterranean, to be among the most powerful. Despite his circumstances, Orfahli is cheerful, thankful to have made it to Italy, and asking his new friends from Sudan to pose for video selfies with him. He also clearly acknowledges that he didn’t want to leave his home in Syria, but unfortunately circumstances made it impossible for him to stay. Once again, it’s a poignant and timely statement about the actual experience of refugees.

The exhibition continues downstairs with two of the most empowering sections of Perpetual Revolution: The Fluidity of Gender and Black Lives (Have Always) Mattered. The Fluidity of Gender combines videos, news segments, mixed media pieces, and documentary photography to explore how the internet has helped foster a community of people who don’t confine to gender norms and over time increased the visibility of queer and trans people in more traditional media outlets like television and magazines. Highlights include Mykki Blanco reciting “I Want a Dyke for President,” Kristen Parker Lovell’s Trans in Media 2, photographs documenting New York’s ballroom scene, and a number of social media accounts that highlight the ethnic diversity of the gender fluidity movement.

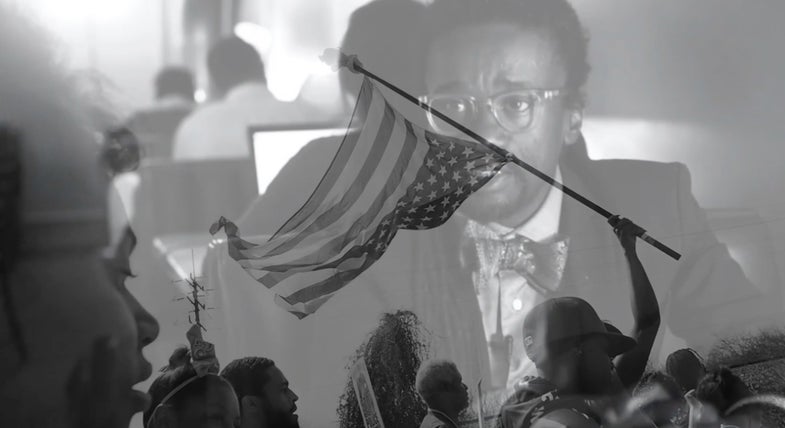

In the adjoining room Sheila Pree Bright’s multimedia piece #1960Now: Art + Intersection takes over one wall of the space. Her video combines footage from the Jim Crow era of activism and the more recent #BlackLivesMatter movement. The multimedia piece draws similarities between the two, weaving together commentary from prominent leaders of the Black liberation movement, pop culture references, and protest footage.

“Dr. King’s policy was that nonviolence would achieve the gains for black people in the United States. His major assumption was that if you are nonviolent, if you suffer, your opponent will see your suffering and will be moved to change his heart,” the late Stokley Carmichael, leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and prominent member of the Black Power movement, says in a recording as images from #BlackLivesMatter demonstrations from the last few years play on the adjoining screen. “That’s very good. He only made one fallacious assumption: In order for nonviolence to work, your opponent must have a conscience. The United States has none.” Bright’s work is presented alongside a projection of works created by Pollen Midwest called A Portrait of Grief,Protest, Power and Love:An Editorial Feature in Memoriam of Philando Castile that includes images from the Castile marches, a portrait of Diamond Reynolds, and a video from Sarah White called Rasing Black Joy.

On the opposite side of the room another multimedia piece from thewaybackmachine titled HowDoYouSayYaminAfrican provides a more discordant perspective. Here thirty-two monitors display a mixture of tweets, news coverage, and viral video in response to #Ferguson—occasionally the sound of a siren emitting from one of the screens will cut through the space—the mixture of mediums is at times overwhelming but incredibly visceral.

Within this gallery the curators once again integrate old with new, highlighting the progress that has been made, but also how much further there is to go. The third wall of the space is dedicated to photographs from ICP’s collection that document the black experience pre-Civil War into the 1960s through studio images, vernacular photography, and traditional documentary work from photographers such as Gordon Parks, Charles Moore, and Bruce Davidson.

These two installations, situated side by side, offer a sense of progress. They provide an inspiring example of the way that disenfranchised groups can harness the power of social media to amplify their voices and propel their causes. This sense of, dare I call it, optimism is quickly shut down with the final two issues that the show examines.

ISIS and the Terror of Images is presented more as a study than a traditional exhibition. Consisting of a number of propaganda videos utilized by the Islamic state to recruit new members, the pieces look to how this group has also harnessed the power of the internet. The videos are well produced, ultimately meant to go viral, and inside the walls of ICP they are presented on computer screens, iPads, and cell phones—the assorted media distribution devices where one would encounter them in the wild.

The final room of the exhibition offers little reprieve. Organized after the presidential election, the space comes with a warning: “This section includes images and language that may not be suitable for all viewers.” Three screens are arranged along one wall, cycling through messages from the “alt-right” that were posted through Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram in the months leading up to the 2016 election. The messages, many that come in the form of memes, spew racist and misogynistic images. The middle screen features messages sent directly from the social media accounts of the Trump campaign, interacting or retweeting messages and iconography that originated from hate groups, like pictures of Pepe the Frog. It is difficult to watch, but ultimately important, because the “alt-right” wouldn’t have gained such traction without internet communities such as 4chan, Reddit, and other social media platforms.

So where do we go from here? While the work on display in Perpetual Revolution poses many questions, it doesn’t seem to offer any answers. But one thing is clear: We do live in an age where we all have a camera in our pocket and a platform to amplify our voices. Will the explosion of visual culture online save us? Or is this simply eroding the power of images created by established photojournalists? Perpetual Revolution certainly makes the audience consider these questions.