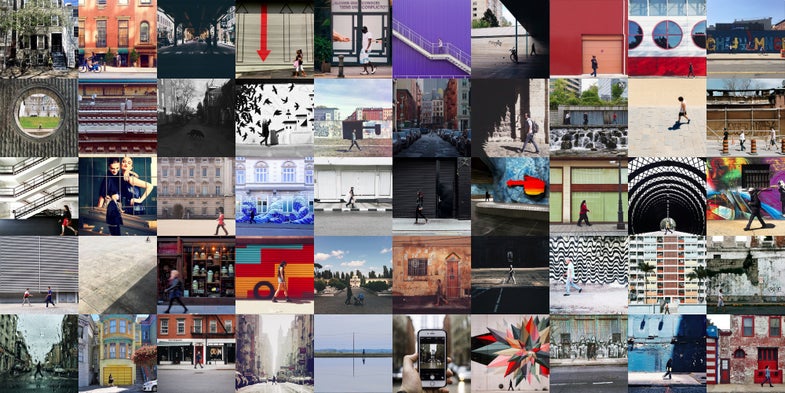

How Instagram Changed Street Photography

The century-old photographic tradition is under threat, but it also has never been as vibrant before

Gary takes a drag from his cigarette as he listened to the Colts defeat the Broncos in his small box radio. He is originally from San Diego, but moved to Los Angeles because he loves the weather. “For 25 years I’ve been homeless. I don’t have to pay rent or anything. I’m disconnected from society.” Intoxicated and addicted with an excessive caffeine itch, I decided to reconnect myself with the Los Angeles people while being high off caffeine.

Just off the corner of Central and in between freeway entrances, Bell shadow-boxed with his headphones blaring. From the distance, he seemed like a maniac, on drugs, unable to cope with his high. However, that was not the case. The man simply enjoyed to box and pretend he was in the actual ring. He came up to me, smelling like he had been drinking excessively all day and said, “They pay these boxers millions of dollars with big ass mansions, and I’m over here sleeping on the street dreaming to be a professional.” Shot this with my iPhone. Let me tell you, it does wonders when trying to keep a low-profile.

Imagine a street photographer and one may most readily conjure the image of someone like Vivian Maier, a solitary figure stalking the streets without company, keeping her work private. But today’s street photographers shatter those clichés thanks in large part to Instagram, a medium that, five years since its launch, has changed not just how these image-makers shoot and relate with their peers, but also the way they display their work and achieve success.

At 20, Pablo Unzueta, is part of a new wave of street photographers raised on Instagram who have developed their craft with better access to audiences and fellow photographers than any previous generation. Unzueta downloaded Instagram years before he bought his first camera in 2012 when he was a senior in high school. He learned to shoot not through any formal education, or, as Colin Westerbeck writes of early street photographers in his book, Bystander, not “by looking into the camera itself,” but by scrolling through his Instagram feed.

When he first started taking photos of homeless people on L.A.’s Skid Row at the age of 17, Unzueta says, “I didn’t know any photographers that were doing similar things until I started becoming a part of the Instagram community. I followed Ruddy Roye—this was long before he had 127,000 followers—and other photographers and started picking up on it.”

Before Instagram, the street photography community was a small one. In fact, according to Marvin Heiferman, the community was so narrow in New York in the 1970s that one could spot Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander shooting on opposite sides of Fifth Avenue on a given afternoon. Today, Instagram has not only widened the definition of who can be a street photographer, but it has expanded our concept of the street—which Westerbeck describes as “any public place where a photographer could take pictures of subjects who were unknown to him and, whenever possible, unconscious of his presence”—to parts of the world, or communities in otherwise well-covered cities that, decades ago, were greatly underserved.

One of the most prominent examples of this effect is Everyday Africa, an account that shares photos of ordinary life on the continent. Photographer Peter DiCampo and writer Austin Merrill began the project in 2012 as a way to combat the cliché images of war, poverty and death that dominate media coverage of Africa, on Tumblr, where it received only modest attention. Since the project jumped to Instagram, however, it’s exploded in popularity. Today, it has 134,000 followers, and has spawned several “Everyday” accounts that embody a similar perspective in locations around the world.

For street photographers likewise looking to transcend traditional media narratives, Instagram has proved an unprecedented platform. The “Instagram activist” Ruddy Roye, for one, says the images and stories,”tailored from the African Diaspora’s perspective,” might not have seen the light of day if newspapers and magazines were the only game in town.

“I remember the days when I was knocking on doors and making calls to editors but to no avail, no one seemed interested in my personal projects,” he told Time Lightbox. Today, he has over 129,000 followers, and in April, he joined many of the traditional media gatekeepers who may have once passed him over for the White House Correspondents’ Association Dinner.

Those traditional gatekeepers in the world of street photography—the museum curators, the gallerists, the newspaper and magazine editors—still hold significant sway. But through Instagram, photographers have found that amassing a vast following can provide a fast track to those power players who, in previous generations, would have been elusive, if not impossible, targets.

Los Angles-based David Ingraham, for one, got representation, gallery shows and publication in magazines since he bought an iPhone 4 and joined Instagram just five years ago. Unzueta’s nearly 66,000 Instagram followers, meanwhile, helped earned him features in national publications, and, in April, an invitation to the New York Times Portfolio Review. He’s still in college.

Still, the street photographers I spoke to talked about Instagram’s impact on business more in terms of “opportunities” like publicity, teaching, and speaking invitations than dollars. When I asked about this, several photographers mentioned the much-publicized fast cash haul of popular street photographer Daniel Arnold. According to Forbes, last March, Arnold had less than $100 in his bank account when he put out a note on Instagram offering to sell 4-by-6 prints for $150 a pop. He got $15,000 in orders in a single day.

While impressive, Arnold’s story is by no means typical. In fact, for some “street style” photographers, Instagram has resulted in a loss of business, according to Brent Luvaas, assistant professor of anthropology at Drexel University. At events like Fashion Week, Luvaas says, longstanding street style freelancers who aren’t churning out steady streams of images on Instagram are finding it harder to get work. “It’s just too much competition with those who are putting out their work for free or cheap,” he says.

Some traditional street photographers have gradually started making the jump to Instagram, but their audiences haven’t necessarily jumped with them. Matt Weber has been photographing on the streets of New York City since 1984. In the last half year, at the urging of a friend, he began posting one or two shots a day to his new Instagram account. Today, he has just over 2,000 followers, a base that pales in comparison to those of younger photographers who’ve spent a fraction of that time on the streets— and which only outnumbers his 13-year-old daughter’s Instagram following by about tenfold.

Weber’s Instagram presence, meanwhile, has had “zero impact” on his business prospects, and he doesn’t anticipate that it will change much in the future. “I hope I’m wrong,” he says. “I hope a year from now I have 150,000 followers and I’m selling prints left and right. But right now it doesn’t change a thing.”

Street photographers today aren’t just contending with more competition online. On the streets, they’re contending with more people wielding cameras — that is, camera-equipped smartphones — than ever before. For Ingraham, the ubiquity of smartphones has actually helped his work, affording him a degree of invisibility he wouldn’t have had shooting with a rangefinder.

“Everyone’s got a phone in their hands, so you can just blend in with the masses,” he says. “To this day, if you’re standing on the street with a legitimate camera, the second you lift that thing to your eye, everyone turns and looks. But if I’ve got an iPhone placed to your ear, I can pretend I’m making a call. I lift and shoot and put it back to my ear. Nine out of 10 times, people don’t realize I got the shot.”

For those who don’t aspire to invisibility, the camera phone has had other positive impacts on their work. Unzueta, for one, takes photos with both an iPhone and a DSLR, but finds the phone more effective when making portraits of L.A.’s homeless population. “When I’m interacting with the phone, I can look people in the eyes. I can continue to talk to them while I take a picture and they can see I’m still paying attention. But if I put a camera in front of my face I no longer have that connection,” he says.

Mobile photography seems to be slowly but steadily winning over curators and gallerists, but in the early years after Instagram’s launch, it faced significant backlash in the photography community. In 2012, Verge editors Chris Ziegler and Dieter Bohn debated whether Instagram filters were “destroying the visual internet,” or whether they were “simply the zeitgeist of our time.” Arguing for the former position Ziegler wrote, “When you apply a parlor trick filter to your photo, you’re not enhancing it, you’re destroying it. You’re robbing it of its realness, its nuance, and replacing it with garbage that serves no function other than to aggrandize your own false sense of artisanship.”

Instagram may very well have enabled a whole generation of false artisans—and even encouraged cliché street imagery by promoting hashtags like #middleoftheroad and #strideby through its Weekend Hashtag Project—but the effect may not be so terrible. Quoted in The Telegraph in 2011, Teru Kuwayama, a photojournalist who is now photo community manager at Facebook, compared the rise of Instagram to the advent of electronic music, both of which stimulated “amateur expression.”

Indeed, from a viewer’s perspective, following street photography in the age of Instagram may be a richer, more fulfilling experience than it’s ever been. As the New York Times notes, curator Leo Rubinfien wrote that Garry Winogrand believed the best photos were those “that told you that the world was a jumble of fragments, that the truth was more complex than any account could be.” The same criteria might apply equally well to platforms for street photography.

Sitting in one’s bedroom, swiping at a screen with the tip of one’s finger through posts from street photographers in New York, Tehran, and North Korea may lack cohesion of quality and geography, but there is a sort of deeper consistency to be found in them. Like individual works by Winogrand or his contemporaries, the collective sum of these voices and subjects and places present a vision of a sort of universal street, one that’s jumbled and messy, but perhaps the best representation of our world that we have.

Featured image credits: @abrilliantdummy @aenede @alcafel @alilfatmonkey @alletirado @amalrachim @anna_scrigni @arieliegallione @atl321 @brotherlylost @bubblysquirrel @carlosdetoro @caropsis @catscoffeecreativity @chrisarrrrr @ciwzz @cobabear @earlmartinezz @eliography @ericvannynatten @george_fikry @heydavina @huxsterized @ig.korea @imbitesized @jeteology @kenny_21