At Home, At War

In early 2011, Denver Post photographer Craig F. Walker and his editor sat down to figure out a direction for...

In early 2011, Denver Post photographer Craig F. Walker and his editor sat down to figure out a direction for Walker’s next long-term project. They wanted something relevant to our times, with both local and national repercussions. They hit on Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. “We felt strongly that this was something that our nation as a whole was going to be dealing with for generations,” Walker says.

In trying to build a photo project around the topic, Walker reached out to several veterans groups, finally connecting with Stacy Bare, a former PTSD sufferer, who organized hikes for veterans. Bare had recently met Brian Scott Ostrom after noticing his truck in a parking lot. It stuck out for two reasons. First was a Marine Corps license plate. Second, the plate read “IED” (Improvised Explosive Device). Bare left his card on Ostrom’s windshield with his phone number. Walker and Ostrom met on a veterans’ hike a few weeks later. The two hit it off, their conversation extending to a coffee shop, where Walker asked Ostrom if he’d be willing to participate in a photo essay on PTSD. Ostrom agreed.

Things looked promising. Ostrom seemed to understand the project, what was involved and the mutual respect and trust it would require. A few days later, Walker called Ostrom, but didn’t hear back. “After a couple days I figured maybe he’d had a change of heart. Maybe it wasn’t right.” The next day, however, Ostrom called Walker to explain. He’d been in a mental health facility for the previous 72 hours after a suicide attempt (his second). “He was apologetic,” says Walker. “I told him he had no reason to apologize. That experience confirmed for both of us that this story needed to be told.”

Ostrom had originally signed up for the Marines after tiring of a dead-end job and seeing his friends venture into drugs. In 2003, while he was in basic training, the U.S. invaded Iraq. His first tour was relatively routine. His second tour dropped him in Fallujah, one of the hottest of the war’s hot zones. In that relentlessly violent environment, Ostrom served with pride and completed the missions he was assigned.

But that period left scars that stuck with him. As with many PTSD sufferers, the effects were minor at first but became more acute over time. “He carried a guilt for things he did and things he didn’t do,” says Walker. These haunted him in the form of panic attacks, rages and severe depression.

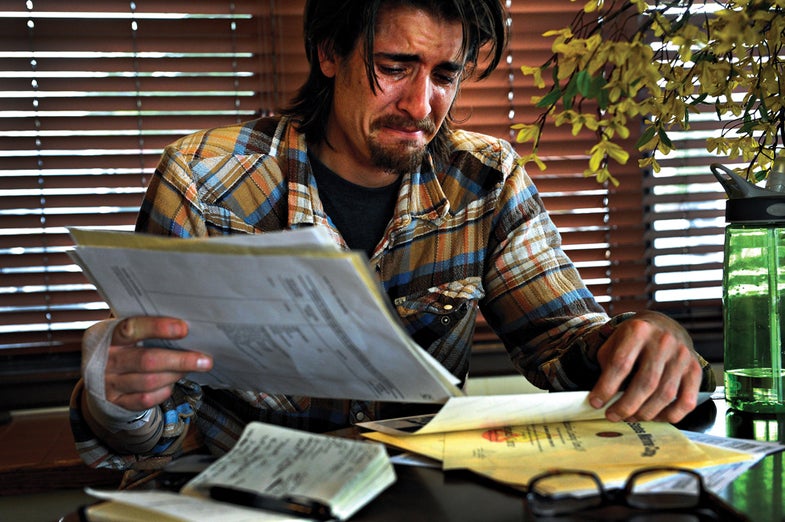

In an act of surpassing courage, for nine months Ostrom gave Walker complete access to his life as he tried to reintegrate into society, struggling with panic attacks, housing, legal troubles and relationship woes. “It was a commitment for him to open his doors like that,” says Walker. “It meant he had to call me when things were bad. I told him, ‘If you’re in the middle of a panic attack or have a hard time dealing with PTSD, I need to be there to share it with you. We wanted to show the dark places PTSD takes people. I’m a photographer. I can’t show it if I’m not there.”

Thankfully, Ostrom called. He called when the police were at his house and he called when his girlfriend left with his anxiety medication after a fight. He called when he couldn’t control his thoughts and when he couldn’t get out of bed and when he was worried about ending up homeless and talking to himself on a street corner. Each time, Walker made the 45-minute drive to Ostrom’s house to see what was going on and capture it as best he could with his camera.

Given the emotionally charged nature of the project, one of the biggest challenges Walker faced was not becoming part of the story. The two are close now that the project is finished, but during those nine months, Walker says, he had to be studiously aware of Ostrom’s status as subject. “I wasn’t there to be his friend. I couldn’t offer him advice. Once, when he had a DUI, he asked if I could give him a ride somewhere. I told him, ‘No. It would change your story. It would alter your life. I’ll come with you and take the bus wherever you want to go, but if I alter the story by giving you a ride, I’ve crossed that line from a neutral, respectful, trusted observer into a friend and helper.’ I didn’t want to misguide him about what we were doing. There is a line, and it’s important to the story that we not cross it. For me to interfere or alter what was going on would do an injustice to Scott because he’s putting himself out there and sharing his story. It’s my job to let it play out, and tell it right, no matter how painful it is. And he understood that. The second time he asked me for a ride, I just kind of looked at him. He laughed.”

Last April, a year to the day after he met Scott Ostrom, Craig Walker was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for feature photography for an 18-picture excerpt from the project (you can view the entire 49-photo series online here). But while Walker says winning the Pulitzer (his second) is “amazing and overwhelming,” he says the main reason he’s happy about the win is the same reason he started the project in the first place—it increases awareness of one of the most difficult and troubling problems of our time. Because of this series, Walker says, “more people become aware of what many of our veterans are dealing with. Scott and I have been contacted by people all over the world. Across generations, from Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam or World War II, even people whose parents were in WWII. You hear all these phrases—shell shock, ‘he was never the same after the war.’ It’s all the same thing. It’s really special that this story is reaching out on so many different levels, both generational and geographical.” We couldn’t agree more.