Finding the Human Element in Richard Misrach’s Landscapes

Look back on 40 years of photos in which solitary figures emerge from grandiose environs

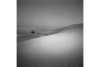

The most striking thing about Richard Misrach’s “Being(s) 1975–2015,” on view at San Francisco’s Fraenkel Gallery (through May 30), is the scale of the images—many up to 4×8 feet, with the photographer’s richly textured nature studies front and center. Oh, and the human beings of the title also make peek-a-boo appearances, as if to show a you-are-here scale of the scenes, like specks caught up within natural forces.

“I rarely shoot ‘portraits’—I have always photographed people at a distance, or with their identity obscured in some form or another,” says Misrach, whose exhibition officially opens tonight. “In general I use the figure as a stand-in for humanity. As the doubled title “Being(s)” implies, [this set] functions both as a noun suggesting our place in the natural landscape and as a verb evoking our larger metaphysical existence. I think the images in the show slide back and forth between those two meanings.”

Misrach’s forthcoming book, The Mysterious Opacity of Other Beings (Aperture, $80), presents “people pictures” in the form of swimmers interacting in the water, a seaward extension of his “On the Beach” series (a few of which are in this show). But much of his environmental imagery over the years has been unpeopled. The work in “Being(s)” seems to border the two, with the humans abstracted but recognizable, often alone. Are they lonely or just solitary? “I identify my subjects as solitary,” Misrach tells American Photo. “Perhaps I am projecting, as I spend a lot of time out in the desert and elsewhere alone and don’t find it lonely at all.”

Misrach often depicts a tiny figure inside a great space by shooting at a distance, achieving vast expansiveness and precise detail within the same frame. He says this has more to do with perspective than specific equipment. “The work in the show, which spans 40 years,” Misrach notes, “has been made with a number of cameras: in the 1970s a Hasselblad and a slightly wide-angle lens; an 8×10 Deardorff view camera with a normal lens (1980s to around 2005); a Hasselblad and a telephoto lens (2005 to the present); and an iPhone. The pictures look the way they do not so much because of the camera I use, but rather because of where I set up and shoot in relation to my subjects.”

In past projects Misrach has explored the destructive aspects of man vs. nature, including the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in Destroy This Memory and the ravages of “Cancer Alley” in Petrochemical America. Yet here the human activity is but a temporal part of a mighty universe. Many of his images seem to be about permanence and fleetingness blended—a sea with a swimmer, a canyon with tiny tourists, a vast white-sands desert with a lone hiker’s shadow…

Which concerns him more—the part that lasts, or the part that emerges and disappears? “Ha! That’s good,” Misrach replies. “I hadn’t thought about that friction, but yes, there is always tension between our lives and the forces bigger than us. For me, making the pictures directs my attention to this relationship, this delicate balance. We are so busy in our day-to-day life we rarely slow down and reflect on how extraordinary being alive is.”