‘The Shape of Things’ at MoMa Traces the History of this New York Institution’s Collection

Explore highlights from MoMa's photography collection through the eyes of one its foremost patrons

The Shape of Things: Photographs from Robert B. Menschel, at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, presents a singular history of the photographic medium through the exhibition’s one-hundred photographs. The show and its attendant catalog, which is also published by MoMa, pay homage to John Szarkowski, the museum’s long-time chief of photography. Looking at Photographs, Szarkowski’s 1977 book, is a required reading in many academic photography programs. In it, Szarkowski uses one-hundred images from MoMa’s photography collection—each with its own short essay—to trace a novel chronology of photography that is closer to a comment on the museum’s particular trove of photos more than it is a definitive history of the medium itself.

The Shape of Things borrows its name from the title of a diptych by Carrie Mae Weems that greets viewers at the beginning of the exhibit. The photos inside share in common that they were all acquired by the museum with the support of Robert Menschel, who has long played a leading role among MoMa’s circle of patrons. The more than five-hundred photographs gifted by Menshcel have been winnowed down for this exhibition and curated into three sets of images; “Truthful Representations, 1840-1930,” “Personal Experiences, 1940-1960,” and “Directorial Modes, 1970s and Beyond.”

Largely black-and-white, the images in the show reflect the tastes and interests of the man who presided over their acquisition by the museum. Robert Menschel, an investment banker by trade, is a senior director at Goldman Sachs but also an amateur photographer and philanthropist. He’s enjoyed an intimate involvement with the museum for forty years, and was invited to join the Committee on Photography in 1977, was then made Trustee of the Museum in the late 1980s and finally appointed President of MoMa in 2002. Menschel came to know several now legendary photographers, the likes of Aaron Siskind and Harry Callahan, whose works make up a substantial portion of the exhibit.

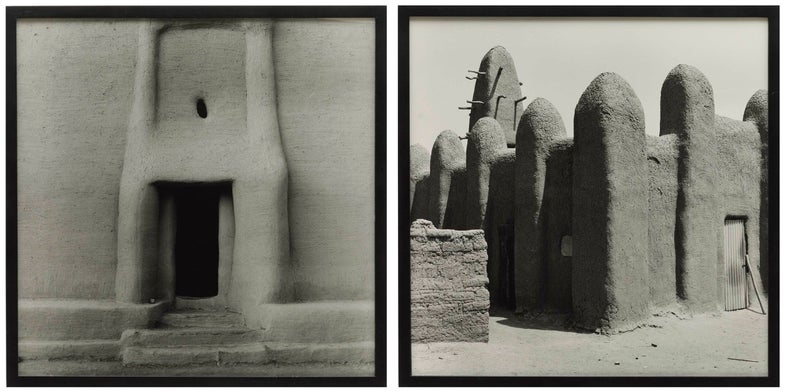

Apparent favorites of the collector include the iconic industrial infrastructure photographed in serial fashion by Bernd and Hilla Becher, Lee Friedlander’s ambiguous outtakes from the urban mise en scène and Callahan’s lesser-known street photographs, a treat for those who only know his “Eleanor” portraits. While Menschel certainly seems to have a penchant for monochrome photos, many of the images on display are contemporary. Works from the last forty years make up the “Directorial Modes” third of the show. Here, outtakes from Joan Fontcuberta’s faux-scientific Herbarium series can be found alongside An-My Lê’s far-away documents of military training (shades of Roger Fenton), and Hiroshi Sugimoto’s atmospheric seascapes.

With a breadth of works spanning more than 150 years of the medium’s history, arranging the show into a digestible format was surely no easy task. However, rather than curate the show based on the evident and recurring themes in the collection—architectural formalism, pseudo-scientific still lives, and the hidden, diminished or distorted human figure—the exhibition is instead chopped into three pieces that offer somewhat ham-handed descriptions of the medium’s history, or the photographs contained therein.

For example, to cast Bernd and Hilla Becher’s post-war Cooling Towers as merely a “Truthful Representation” is to overlook the gulf the between their work and August Sander’s Weimar-era serial portraits. To suggest that the primary concern of photographers from the inception of the medium until 1930 (a nearly century-long gap during which Modernity came fully to form) was solely the verisimilitude of their images is a gross over-simplification that disregards dozens of photographs that would present evidence to the contrary, Bayard’s Self Portrait as a Drowned Man, or the Countess of Castiglione’s many self-portraits masquerading as mythical figures being just two examples.

Mid-century photography, the kind we associate with the photographs of Lee Friedlander, Harry Callahan and Robert Frank, has been reduced to a collection of “Personal Experiences.” While certainly the 20th century can be said to have birthed consciously subjective photography, of the sort that we’d today call “expressive,” to label the works in the exhibit taken from 1940-1960 this way seems to deny the personal impositions of photographers from the rest of the medium’s history, past and present. For my money, the honesty of John Coplans’ unflattering self-portraits, one of which is exhibited later on in the show, seems like a better candidate for this category.

Either Mr. Menschel is not terribly fond of the dramatic shifts that the photographic landscape has seen in the last 15 years, or newer images from the collection were not selected to join works taken since the 1970s up until “today” in the exhibit’s final third, “Directorial Modes.” We are informed by wall text that this title refers to the Postmodern photographic trend of staging photographs, showcased here most effectively by David Levinthal’s macro shots of toy soldiers and dolls and Fontcuberta’s documents of composite flora. But what photographs are more contrived than the plastic portraits churned out by Nadar and Julia Margaret Cameron’s precious cherubs, all shot more than a hundred years ago? This curatorial title, like the previous one, is not necessarily inaccurate in its description of the images it is designed to pertain to, so much as it is seems to miss what makes photos from this time period different from those that came before, in all but the most cursory of ways.

To be fair, the show presents itself as a non-comprehensive history of photography and images from different time periods are shuffled between the three sections of the exhibit (though in my opinion only in such a quantity as to be confusing). For most, the show will provide a pleasant survey of the medium’s broad strokes, as shown through the work of some of its greatest masters. To boot, it also hews fairly close its own stated curatorial objective and provides an interesting exhibitional analog to the Szarkowski’s Looking at Photographs. The show seems formulated for casual viewing rather than intense inspection and taken as breezy “greatest hits” collection, makes for an enjoyable visit to the Modern. The Shape of Things is on view until May 7th, 2017.